The Most Perfect Day

by Roxie Milam Wallace and Jeff Wallace

The blue sky was faultless, and the air crystalline—the most perfect First Sunday in June Decoration Day anyone could remember. The old man, Palestine Mountain, sat content, robed in the verdant splendor of cottonwood trees, white oaks, and magnolias. A gravel road sash twisted in the bright sunshine from the blacktopped #22 Highway, through the hardwood growth and Kudzu, around the side and up to the top and his crown—a gentle clearing of mown grass–the community cemetery, decorated with majestic spires of granite and marble headstones dating back to decades before the civil war.

Warmed summer breezes twisted green leaves and fragile ribbons that bound crepe-paper flowers—the homemade bouquets that honored gravesites annually during family “Decoration Days” and reunions throughout the South for decades until plastic flowers came onto the market. The sheer fragility of crepe paper wreaths made them all the more beautiful and precious to color the gravesites, the emotional interactions, and the pleasurable entertainment of friends and relatives gathering to pay homage to ancestors and to reminisce about recently departed loved ones.

Pictured, left to right: small girl Penny Townsend, adult lady Faye Hart Wilson, in front of her Peggy Townsend, in background Linnie Britt Milam, foreground Bertha Britt, in back of her Thelma “Rooster” Hart Hopper, Ruth Hart Townsend, Louise Hart, Kaye Hart McLemore, Charles Perry.

The last two people named were married later that year.

Bertha Britt and her daughters, as well as her maiden sisters Ada and Millie, along with as many granddaughters as she could persuade to help out, had been making crepe paper flowers since the last Christmas, preparing for this June day. The stretchy, brightly colored paper was inexpensive—each folded and creased roll cost only 10 cents. Whenever anyone traveled to Lexington, TN with a list of items to purchase—coffee, sugar, or flour in the grocery category, or perhaps, fertilizer, cottonseed, snuff or rolling tobacco in the “have to have”—he was instructed to pick up a packet or two of the crepe paper.

Only the paper needed to be purchased; baling wire and twine could be found around the house or barn. Rounded petals were cut with scissors, several at once, from red, yellow, blue, or purple folded lengths of paper, each stretched out with the thumbs to form a bubble-like lump that imitated the bud area of a blossom. One-half inch streamers were cut from the green bundles, then wrapped around seven inch sections of baling wire to become the floral stem. As each individual petal was placed just below a loop that had been fashioned at one end of the wire, twine was used to secure it to the stem. If one was lucky, she might have some very thin metal strands the man of the family had taken from inside a section of rubber covered, heavier wire used with farm machinery. These lengths held the petals together more securely and was easier to use than twine.

As each flower was finished, it was placed into a clean fruit jar that had previously held food the family preserved the previous fall and opened to be cooked for meals during cold winter days. By the time June arrived, every flat surface in the house would be covered in bouquets of bright blooms so that it resembled a commercial florist. Bertha was proud if her house was so full of flowers that they were in the way, and it was difficult to do the household chores of cooking, cleaning and washing clothes. Today, she was very pleased that it took ten individuals to remove cardboard boxes of paper flowers from the old ford pickup, along with the fresh roses, cannas, and peonies the family had picked from beds along fences and across the high, front porch of the house. However, there were so many Britts and Wallaces along with kin of other surnames buried at Palestine, the graves were barely decorated to her satisfaction. Once the flowers were lined up along the mound of dirt behind each tombstone, someone would place a ladder-back chair under the shade tree, at the southwest edge of the cemetery, for her. Then, she would forget the flowers, take a dip of snuff, and prepare to hold court among her many progeny and friends.

Other high royal priestesses of ritual and tradition in this family of Southern women walked somberly across the open spaces of the mountain top in their freshly pressed, cotton dresses, minding their newly coiffed, beehive hairdos. They reverently conveyed the carefully created decorations in outstretched arms to markers of loved ones who had passed on too soon. Along the way, they made sure to stop and speak to everyone they recognized, some kith and kin they had not seen since the year before. Responsible for making these reunions meaningful and a cherished memory for so many, they were very good at it. Most eventually gathered under the shade tree to visit with Bertha’s family, where laughter replaced solemnity as people reminisced about their youth.

Sometimes the jokes became a bit ribald as cousins shared details of escapades and adventures they had experienced as children. Often people would be teased about personality traits and idiosyncrasies. Reble Britt Carpino, Rooster (Thelma) Hart Hopper, and Imogene Woods Britt would almost strangle themselves with guffaws every time they got together.

Three beautiful, statuesque ladies, standing 5 feet, eight inches to 5 feet, ten inches tall, they were gifted by God with very ample bosoms–each had a 40D chest and a sense of humor to match their “bigger than life” physiques. A delightful act that everyone looked forward to was the performance put on by Reble, Rooster, and Imogene as they hassled one another as to which bosom was holding up the best and which ones had sagged to waistlines and beyond.

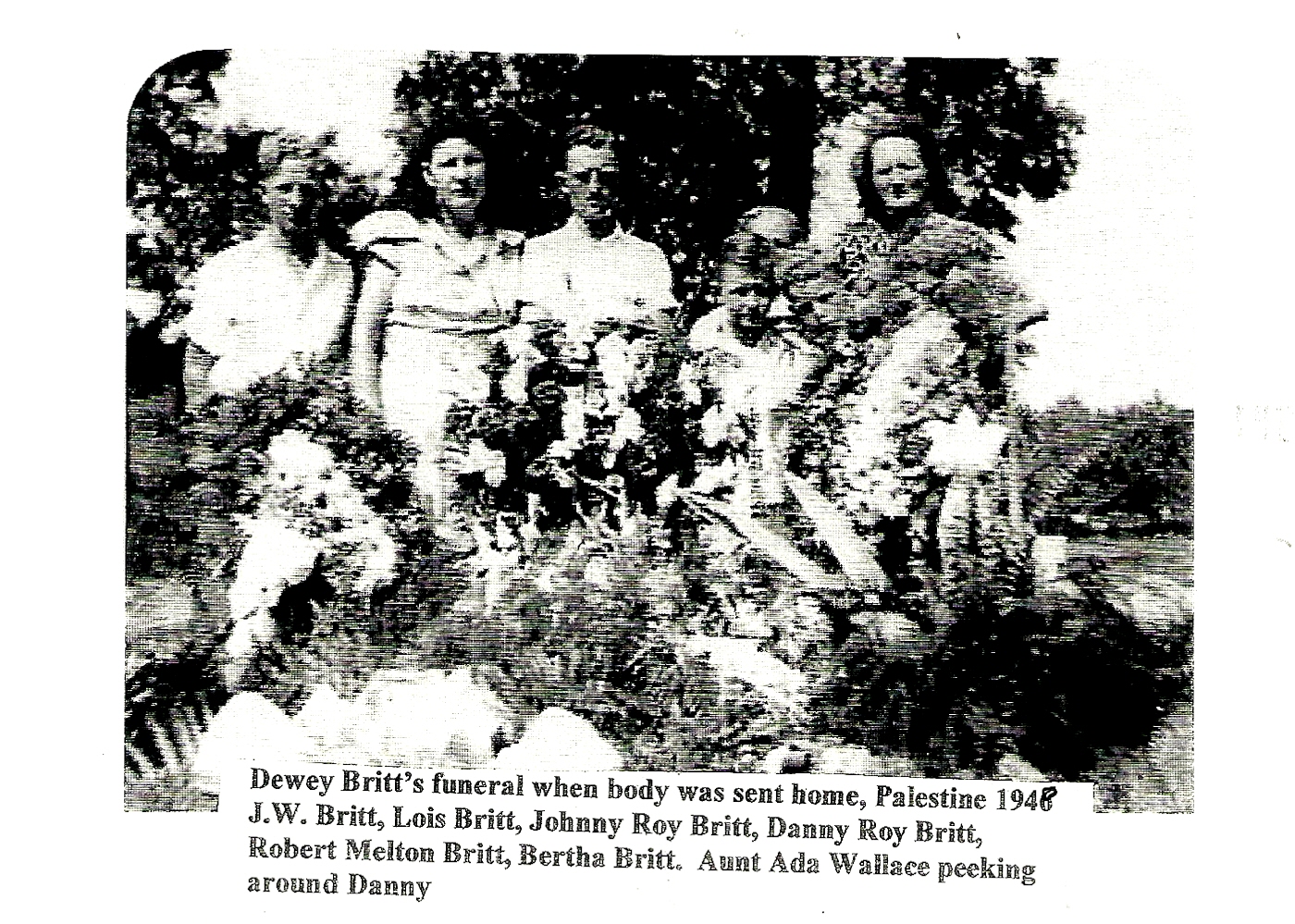

Farther toward the East, small groups would stand around tombstones, shaking hands and embracing with tears in their eyes. Two small, carved stones stood at the west end of short mounds, proclaiming that they memorialized the lives of Jimmy and Garry Waddle, sons of Helen Britt and Odis Waddle. The first stone identified Jimmy who, tragically, died at birth. The second honored Garry, whose story was even more affecting.

Every year, folks were reminded of his death, and few could contain their emotions. The energetic, five-year-old had awakened one morning complaining of pain in his legs and telling his momma that he’d dreamed last night about being shot by an Indian’s arrow. Western programs and movies were popular at that time.

Doctors determined that Garry was suffering from spinal meningitis. With few and inadequate treatments available, he lived for less than a week. Those two little headstones, resting side by side, could wring tears from the hardest of hearts. Standing beside them, gentle words were always spoken to the family by the dear, Christian man Harold Pollock.

Most of the deceased Pollock family members were buried at Chapel Hill Baptist Church cemetery, about five miles away. However, they were also related to the Wallace/Williams/Holmes families, so many Pollocks attended the Palestine reunion each year. Harold, the second oldest boy in the George Pollock group, was loved and revered by everyone. His smiling demeanor, gentle voice, and wealth of information about “doings” in the community made him a welcome sight to everyone.

Some years, Harold’s wife Vivien, sons Andy and Marty, with daughter Nila would accompany him. Other times, only Harold and Andy would attend. Everyone knew they could look forward to seeing father and son. A man of Christian convictions, Harold Pollock could gently speak to those in distress and soothe their anxieties, always advising folks to lean on Jesus, and He would make things right. He also knew, many of them firsthand, genealogical stories and family tree details for almost every surname carved into the ancient granite markers. Harold was related to so many of the families.

He was kin to the Wallaces because his mother Ida was a Wallace, sister to Ethridge, Bud Wallace’s father. One Williams group came from Harold’s mother’s sister Elenor Wallace Williams. The Harts were related because Samuel Wallace, Ethridge’s father, was a brother to Marion Hart’s second wife, and Sam married Marion’s granddaughter Nancy. In one-way or another, everyone on Palestine Mountain was related to everyone else.

Finally, it was time to meander down toward the grounds of the Palestine Presbyterian Church at the foot of the mountain, to the annual “dinner on the ground” spread in the shade, under trees by a natural water aperture. The spring had brought pioneers to settle land and build houses in the area. Every first Sunday in June, for one hundred, fifty years afterward, they or their progeny had gathered beside it to honor their dead by decorating graves and to reunite with friends and family over a meal of the best foods their agriculture, animal husbandry, and cooking skills could provide.

Today, the menu would be composed of some of the same dishes, recipes for which had been handed down from generation to generation for one and one-half centuries. There was the big pot of broken, green beans cooked for hours in chunks of cured pork, always contributed by Aunt Mildred Hart McLemore: cornbread dressing prepared in a large, 9” by 13” pan, with long pieces of stewed chicken that was the specialty of Aunt Ruth Hart Townsend; Ruby Britt Fryman never forgot to bring miniature, chocolate fudge pies; the buttermilk cornbread, brown and crunchy on the outside, moist and sticky on the inside was always made by Grandma Lula Mae Hart Wallace Baker; the best chocolate pie ever tasted, created and double-cooked by Linnie Britt Milam would be devoured before everyone could get a bite; Roxie Milam Wallace, mother of the Wallace younger generation, could be depended on to provide a succulent dessert—fresh strawberry tart or moist coconut cake; Ginny her sister was expert on potato salad with deviled eggs, and her carrying utensils would be empty after everyone had eaten; and, Aunt Reble’s super thin French cookies were an exotic touch. Some relatives would bring homemade pickles, especially the bread and butter recipe, while others put out casseroles of rich, golden squash, crisp fried, green tomatoes, luscious field peas, Irish potatoes in a skillet with onions, gallon jugs of candy-sweet tea, biscuits with country ham, and of course the obligatory banana pudding made in the “from-scratch”, country way with fresh eggs and cream.

___________________________________

This year everything had changed. Halleluiah! Now, the families walked many paths down Palestine Mountain. They had grown in size to numbers unanticipated. They walked hand in hand in groups, the young with the old from ages passed, all the way back to the beginning. The church expanded until it became a huge open pavilion, a beautiful impressive structure in a meadow that seemed to go on for miles and miles of gently rolling hills beside a river of sun dappled light. Thousands of faces beamed and smiled at their children and each other, greeted old friends with handshakes and pats on their backs, mothers cried and hugged one another. With daughters, sons, and fathers, they all moved together toward the church sanctuary and joined, singing there all the hymns they dearly loved, “Shall We Gather at the River,” “In the Sweet Bye and Bye,” “We’re Marching to Zion.” These Christians’ marching orders were over forever. They had arrived at their final destination, just as they had practiced at Palestine on the “Most Perfect Day.”