J B Caudle�s Marine Magazine Article

The Leatherneck, July, 1944 Vol XXVII, No

8, p.34

Caudl-JB.doc

Magazine article

Sky Spies

Marine photo-recon fliers are charting pathways

for Allied thrusts into heart of Japan�s empire

By Sgt. Bill Miller

Deadly bloom of ack-ack

flowered in the skies over Truk harbor.

Through a rift in

the clouds, Jap gunners could see one of two American Liberators daring

to fly over that most formidable of Nippon�s Central Pacific bastions.

Nip spotters at first

had reported the raiders as bombing planes, but now they knew better.

They were United States Marine photographic reconnaissance planes, sure

harbingers of trouble.

Those

far-ranging sky giants, with cameras instead of bombs in their bellies,

were familiar and highly unwelcome sights to the Japs. Day after

day they came, first over Guadalcanal, then over the Russells, New Georgia,

New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Eniwetok _and

now over Truk. Always after them came the bombers, the warships and

the invasion fleets.

That flight over

Truk, on 4 February, 1944, followed by smashing attacks which exploded

the �impregnable fortress� myth, spotlighted a little known phase of Marine

aviation. Aerial �photo-recon� is said to be responsible for eighty

per cent of all military intelligence in modern war, but few flights are

made public when their daring and vital nature can be appreciated.

Truk was the target

of another Marine photo-recon foray early in 1943, when the most advanced

Allied airfield was on Guadalcanal. One of the longest and most daring

flights ever made, it came within sixty miles of its goal and did succeed

in getting pictures of Puluwat, 125 miles west of Truk.

In weather as dirty

as only the Solomons variety can be, two Liberators of Colonel Elliott

Bard�s Marine Photographic Squadron 154 took off from Henderson Field,

bound for Truk. One of the planes turned back in the heavy storm,

but the other kept on, up the slot to Bougainville, then north over the

vast stretch of open sea.

Aboard the plane

were Col. Bard, Major Andrew B. Galatian, Jr., pilot, Commander J.L. Greenslade,

Navy observer, and a full crew of enlisted Marines. Forced off course

by storms, they finally reached a point midway between Truk and Puluwat.

To the east, clouds and the sun made Truk invisible, but they could see

Puluwat�s reefs beneath the clouds on the west. So they turned west

and took pictures of Puluwat.

All the way back

to Guadalcanal, they fought their way through storms, arriving with only

thirty gallons of fuel left in the tanks, enough to keep them in the air

eight minutes. After stretching the range of their PB4Y-1 to the

limit, they were unable to circle Henderson Field as required in ordinary

landings and had to radio ahead that they were coming in straight.

For the record, Australians

flew American-built Hudsons on two photo-recon raids over Truk in January,

1942, while they still held Rabaul. Despite heavy ack-ack and attacks

by Jap planes, they filmed twelve cruisers and destroyers and an aircraft

carrier in the harbor and bombers packed wing to wing on one island airstrip.

Three weeks later, Australian-manned Catalinas dropped the first bombs

on Truk.

Col. Bard, now commanding

Air Regulating Squadron 9 at Cherry Point, was skipper of VMD-154 during

its fourteen months of operations in the South and Central Pacific.

Commissioned early in 1942, it was the first Marine photographic squadron

to go into combat, its vanguard arriving overseas 5 October, 1942.

Army planes, under Navy control and using photographers from a Marine observation

squadron, handled all photo-recon in the Solomons from July to October,

1942.

Original function

of the airplane in war was reconnaissance. There were Marine aerial

observers in France during World War I, but they took no pictures.

One of those aerial

observers was Sgt. George C. Morgan, who became an ace air cameraman for

the Corps after the war. He served on mapping details in Haiti, Nicaragua

and Panama and was cited as an aerial photographer in the Nicaraguan campaign

of 1927.

In 1921, Colonel

Christian F. Schilt, now commanding 9thMarAirWing at Cherry Point, mapped

coasts and rivers of Haiti and Santo Domingo. He flew a de Havilland

with a K-1 camera attached to a special frame back of the rear seat.

That same year, Lieutenant

Eugene Rovegno took aerial photos of President Harding�s yacht off Quantico,

developing the film in flight and dropping finished prints aboard the Mayflower

when it docked at Quantico eight minutes later. So far as is known,

that was the first time in history photographs were taken, developed and

printed aboard a plane.

Colonel Hayne D.

Boyden was responsible for most of the pioneer work in Marine air photography.

He was the first Marine officer to attend the Army school of aerial photography

at Chanute Field, Ill., in 1923. He probably has taken more pictures

from the air than any other flier and has survived so many crashes that

old-timers call him �a man who can�t be killed.�

Landing force exercises

of the Atlantic Fleet on the beaches of Culebra Island were filmed by Col.

Boyden in 1924 to 1927, with Corp. Hubert H. Dogan as his photographer.

Since 1922 he has done much aerial mapping, including 500 square miles

of northeastern Nicaragua in 1932.

Among Marine officers

who have done much in the field of aerial photography during this war are

Colonels Raymond E. Hopper, William C. Lemly and Ernest E. Pollock.

When VMD-154 was

formed, early in 1942, it was given three F2A-3s (Brewster Buffaloes),

fitted with F-56 automatic cameras. These planes and two SNJs which

replaced them were used only in training.

In Pacific operations,

�heavies� like the PB4Y-1s do strategic mapping and reconnaissance, while

fighter types are used for most of the daily tactical field coverage.

With the new continuous strip cameras, speedy fighters can zoom over enemy

strongpoints, shooting pictures from altitudes of 300 feet or less and

getting away before enemy defenses are alerted.

Majors Mike Sampas

and Herman A. (Hap) Hansen won DFCs for such low oblique flights in the

Solomons. Major Sampas flew an unarmed fighter plane on photo-recon

missions over the Kokumbona area every other day from 19 October to 1 November,

1942, gaining valuable information despite heavy ack-ack and attacks by

Zeros. Major Hansen made similar fights and was shot down once, crash-landing

in the ocean under Jap gunfire. Despite injuries, he made his way

to shore and returned immediately to duty.

VMD-154 was cited

for discovery of the cleverly camouflaged Jap airfield at Munda, which

the Allies captured after they let the Nips finish building it. Intelligence

reports of activity there were conformed by air photos which showed telltale

signs of the airstrip under coconut trees.

Aerial photography

is largely an enlisted man�s show, although officer pilots get most of

the glory. Photographers, gunners, radiomen and flight mechanics

on the PB4Y-1s, as well as most of the ground personnel, are enlisted men.

Four Marine sergeants,

all aerial photographers with the observation squadron which preceded VMD-154

in the islands, won Air Medals for their part in discovery of what is now

Henderson Field on Guadalcanal while the Japs were building it in 1942.

MTSgts. Marcus N.

Harper, J. Morris and W.L. Peak and TSgt. H.E. Collier took the pictures

on the first two flights over Guadalcanal in July, 1942. Army Flying

Fortresses under Navy supervision were used for the 2000-mile missions

from New Caledonia.

�We had a running air battle

with five Zeros for twenty minutes,� MTSgt. Harper recalls of one flight,

�and our gunners swapped plenty of lead with the enemy fighters.

The tail gunner bagged one Zero and the rest were driven away.�

Harper had two tours

of overseas duty. Most of the second was on the ground, but he got

fifty combat hours over the Gilberts and helped photograph gun emplacements

on Betio before invasion. VMD-154 did the reconnaissance for the

Tarawa thrust, handicapped though it was by lack of fighter planes for

low obliques which might have revealed more of the island�s hidden defenses.

Shooting pre-invasion

pictures of Tarawan was no picnic. Many missions were flown, all

for long over-water distances, and the ack-ack was always heavy.

One of the planes

overshot the target when the tiny isle was covered by clouds. After

searching for several hundred miles, it headed back to its base.

Suddenly three Zeros

pounced upon the Liberator. Just as suddenly, the Marine crewmen

found themselves right over Tarawa, only 500 feet up and a perfect target.

They lost no time in hurrying upstairs before the pokey anti-aircraft batteries

opened fire, then beat off the Zeros.

�Blow by Blow� accounts

of front line action on Bougainville were photographed daily by VMD-154,

and films were dropped to a ground photography unit which was in charge

of Tsgt. Harley S. Hardin during the initial Marine landing at Empress

Augusta Bay. Hardin, who is credited with assisting in discovery

of the Munda airfield, had his closet brush with death on Bougainville.

�During the first

few days, we encountered six enemy strafings. Although we had supremacy

of the air, a Jap plane would sift through occasionally and do considerable

damage along the beach. We were without foxholes the first day, and

several machine gun bullets narrowly missed me.�

Marine aerial photographers

are trained at the Naval School of Aerial Photography at Pensacola, Fla.,

and most of them are qualified gunners and bombardiers as well as skilled

cameramen.

MTSgt. Lloyd H. Wolf

was taking pictures on a flight over Munda when eight Zeros jumped his

plane. He immediately abandoned his camera hatch and swung his twin

fifties into action.

�One of the Japs

made a low pass on the starboard side of the plane. He came within

range and I put my bead on him.

�The Zero seemed

to stop in mid-air as I fired a quick series of rounds. My tracers

tore into his fuselage. Our turret gunner saw him plummet into the

water after busting into flames.�

During the sojourn

of VMD-154 in the Pacific, in some 300 missions, there were remarkably

few attacks by enemy aircraft. The wary Japs did not come too near

the heavily gunned PB4Y-1s except when they had great superiority in numbers.

No planes were lost in actual operations.

In one epic battle,

eight Zeros jumped a Liberator returning from a photo-recon mission over

Munda. Having no belly turret, the pilot, Lieutenant Gordon E. (Gig)

Gray, headed for the water. He flew so low that crewmen say the wing

edges hit wave tops.

Sgt. Earl Anderson

and PFC Jack Tarver, gunners, blasted two Jap planes into the drink, and

two others were driven off smoking. Knowing the PB4Y-1 had no direct

fire in front, two of the Zeros attacked head-on. The Liberator was

aimed directly at one of them, increasing its turning circle so rapidly

that the Jap pilot fell out.

When Lt. Gray got

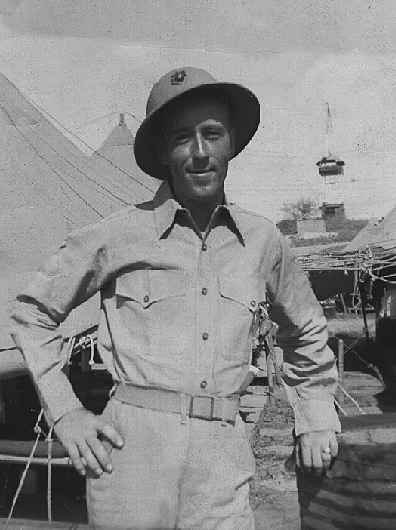

three slugs in his arm, TSgt. James (Pappy) Caudle, flight mechanic, took

the controls until things cooled off and Lieutenant Earl Miles, copilot,

could take over. Sgt. Harry Schaub, radioman, stopped a bullet with

his eye. Photographers on the flight were MTSgt. George Brown and

MTSgt. Levert E. Jones.

Their plane was beat

up so badly that they had to flash a warning ahead and land straight on

Henderson Field. They nosed over in landing, and traffic to Guadalcanal

had to be diverted to Espiritu Santo until the mess was cleared up.

Attached to 1stMarAirWing,

VMD-154 had its difficulties in the early days of the Pacific offensive.

Maps were scarce and hard to read, since the islands lacked such distinguishing

features as roads.

�Most of the maps

preceding our occupation were charts made around 1850.� Col. Bard

explained. �Consequently, they were very much out of date, as the

rivers had changed courses, beaches had built up or receded, and about

their only use was to show the general contour of the islands.

�However, maps covering

nearly every major island in the South Pacific, made from late photographs,

are now available, plus a great many photographs of particular locations.�

Weather is always

the toughest problem, since it determines whether a pilot will come back

with his mission accomplished. More than one campaign had been held

up when weather prevented aerial reconnaissance.

�One point we were

always careful about.� Col. Bard recalls, �was that planes and crew

must be prepared to take off at a moment�s notice, to take advantage of

breaks in the weather. We habitually kept a standby crew for close

jobs during all daylight hours, and sent out daily missions, morning and

afternoon, on flights of 400 miles or more to get the pictures required.

�On one mission,

the mapping of Vanikora Island, thirty-seven hops were flown before the

weather became ideal for mapping.�

VMD-154 has left

the islands, but another Marine photographic squadron is there, under command

of Lt. Colonel Edwin P. Pennebaker, Jr. That outfit already has plenty

of work chalked up to its credit, including the raid on Truk last February.

There will be few

milk runs for these aerial advance men as the Allied ring tightens on Japan�s

inner empire. When Marines spearhead the final assault, they will

follow a path where photo-recon fliers have charted every step.

Sky Spies

Marine photo-recon fliers are charting pathways

for Allied thrusts into heart of Japan�s empire

By Sgt. Bill Miller

Deadly bloom of ack-ack

flowered in the skies over Truk harbor.

Through a rift in

the clouds, Jap gunners could see one of two American Liberators daring

to fly over that most formidable of Nippon�s Central Pacific bastions.

Nip spotters at first

had reported the raiders as bombing planes, but now they knew better.

They were United States Marine photographic reconnaissance planes, sure

harbingers of trouble.

Those

far-ranging sky giants, with cameras instead of bombs in their bellies,

were familiar and highly unwelcome sights to the Japs. Day after

day they came, first over Guadalcanal, then over the Russells, New Georgia,

New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Eniwetok _and

now over Truk. Always after them came the bombers, the warships and

the invasion fleets.

During the sojourn

of VMD-154 in the Pacific, in some 300 missions, there were remarkably

few attacks by enemy aircraft. The wary Japs did not come too near

the heavily gunned PB4Y-1s except when they had great superiority in numbers.

No planes were lost in actual operations.

In one epic battle,

eight Zeros jumped a Liberator returning from a photo-recon mission over

Munda. Having no belly turret, the pilot, Lieutenant Gordon E. (Gig)

Gray, headed for the water. He flew so low that crewmen say the wing

edges hit wave tops.

Sgt. Earl Anderson

and PFC Jack Tarver, gunners, blasted two Jap planes into the drink, and

two others were driven off smoking. Knowing the PB4Y-1 had no direct

fire in front, two of the Zeros attacked head-on. The Liberator was

aimed directly at one of them, increasing its turning circle so rapidly

that the Jap pilot fell out.

When Lt. Gray got

three slugs in his arm, TSgt. James (Pappy) Caudle, flight mechanic, took

the controls until things cooled off and Lieutenant Earl Miles, copilot,

could take over. Sgt. Harry Schaub, radioman, stopped a bullet with

his eye. Photographers on the flight wereTSgt. George Brown and MTSgt.

Levert E. Jones.

Their plane was beat

up so badly that they had to flash a warning ahead and land straight on

Henderson Field. They nosed over in landing, and traffic to Guadalcanal

had to be diverted to Espiritu Santo until the mess was cleared up.

Attached to 1stMarAirWing,

VMD-154 had its difficulties in the early days of the Pacific offensive.

Maps were scarce and hard to read, since the islands lacked such distinguishing

features as roads.

�Most of the maps

preceding our occupation were charts made around 1850.� Col. Bard

explained. �Consequently, they were very much out of date, as the

rivers had changed courses, beaches had built up or receded, and about

their only use was to show the general contour of the islands.

�However, maps covering

nearly every major island in the South Pacific, made from late photographs,

are now available, plus a great many photographs of particular locations.�

Weather was always

the toughest problem, since it determined whether a pilot would come back

with his mission accomplished. More than one campaign had been held

up when weather prevented aerial reconnaissance.

Submitted by Shirley Caudle Miller

|

![]()

![]()

![]()