POTTERY MAKING IN HENDERSON COUNTY

Extracted from: Samuel D. Smith and Stephen T. Rogers. 1970. A Survey of Historic Pottery Making in Tennessee. Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Conservation, 1979

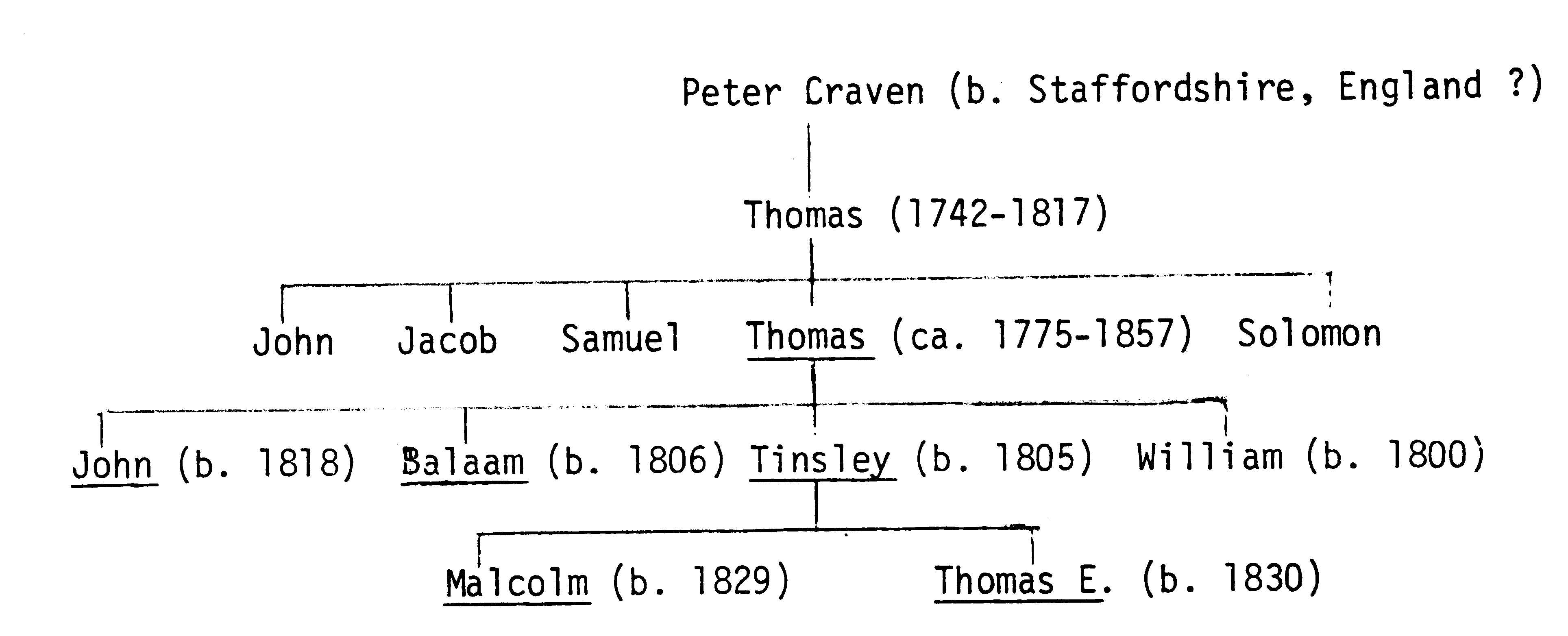

The ceramic history of Henderson County is very complicated and has its origins in an older North Carolina pottery tradition. Of the ten potters listed on the 1850-1880 census schedules for Henderson County, five were members of the Craven family from North Carolina: Balaam, John, Tinsley, Malcolm, and Thomas. A sixth potter, John Hughes, was living in the household of John Craven, and the remaining four potters, Mark Mooney, Alexander Fesmire, and Richard and Riley Garner, all had direct ties to North Carolina.

Much has been written about pottery making in Randolph County, North (Auman and Zug 1977), and specifically about Peter Craven (Crawford 1964). The patriarch of the Tennessee Craven family was Thomas Craven, born in North Carolina about 1775. He was the oldest son of Thomas Craven and the grandson of Peter Craven. Thomas Craven, Jr., was listed on the 1800 and 1810 censuses for Randolph County and on the 1815 tax list.

Thomas's sons John, Tinsley, and William moved to Henderson County, Tennessee, in 1829, and Thomas and a fourth son, Balaam, were in Clarke County, Georgia in 1830 (1830 U. S. Census, Clarke County Georgia). By 1840 Thomas and Balaam had joined the other Cravens in Henderson County. An additional generation of potters appeared by 1850 when Tinsley's sons, Malcolm and Thomas E. Craven, were listed as potters (1840-1850 U. S. Census, Henderson County).

An abbreviated Craven family chart is presented below in order-to illustrate the relationship between generations. The individuals involved in pottery making in Tennessee are underlined.

The Fesmire family seems to have been associated with the Craven family for many years. Balaam Fesmire was born in North Carolina, presumedly in Randolph County. Balaam moved to Henderson County, Tennessee, about 1829, the same time the Craven family moved west. In 1850, Balaam Fesmire was living next to Balaam and William Craven (see 40HE37). The repetition of the Biblical name Balaam in both families was probably not coincidental and is additional proof of the families' close ties. While Balaam Fesmire was never listed in the census as a potter, it seems logical to assume he played some part in the pottery-making activities in Henderson County.

40HE35

Balaam Fesmire's son Alexander was listed as a potter on the 1870 census for Henderson County and apparently was working at the 40HE35 site. Thomas E. and Malcolm Craven (sons of Tinsley) were also listed as potters and were living next to Alexander Fesmire in 1870.

This Fesmire-Craven pottery produced salt-glazed stoneware in the standard utilitarian forms, and tobacco pipes and ceramic animal figurines were also made. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the ware concerns several sherds from large ovoid-shaped jars that have an appliqued "rope-like" design around the midsection. Two large jars in private collections have this identical applique and clearly were made at this pottery… (Beasley 1971: No. 123).

The exact period of production at this site is not known, but a large quantity of waster sherds was found, suggesting a long operation. The pottery probably active from before 1870 until at least the 1880s.

40HE36

The recording of this site was largely based on information provided by the former landowner, a life-time resident of the area. The pottery was located at the end of a hollow known locally as "Old Potters Shop Hollow" (John Britt, Henderson County, personal communication).

The early history of this pottery is unclear. Thomas Craven and his sons, John and Tinsley, were probably associated with this operation. John, Tinsley, and Tinsley's son, Malcolm, were all listed as potters on the 1850 census. In 1850, Malcolm had recently married and was living next door to his father and his uncle John. Living in John's household was John W. Hughes, also a potter. All four of these potters probably were associated with this site; however, one or more additional kiln sites could exist in this general area.

The 40HE36 pottery was probably out of production by 1860. Tinsley Craven died in Lexington, Tennessee in·1860 (Cravens 1957:6), John did not appear on the Henderson County census schedule after 1850, and Tinsley's son, Malcolm, moved to a different part of the county by 1860 (see 40HE35).

A large waster sherd pile was once evident at this site, but heavy vegetation prevented the collection of an artifact sample during the survey.

40HE37

While both the history and the location of this site is somewhat speculative, it was felt that enough information was obtained to assign a site number. By 1850, Balaam and William Craven had settled in this area northwest of Lexington, Tennessee, 10 miles from their brothers Tinsley and John (see 40HE36). They were joined by Balaam Fesmire. The 1850 census shows these three men living next to each other. Balaam Craven was the only one listed as a potter, but Balaam Fesmire's son, Alexander, was a potter in later years (see 40HE35) and probably learned the pottery trade at this site.

Both William Craven and Balaam Fesmire received land grants in this area (West Tennessee Land Grant Book 3, p. 181; Book 7-A, p. 865, Book 9, p. 517; and Book 12, p. 424; Tennessee State Library and Archives). Long time residents of the area still remember the Bill Craven homeplace. The pottery was probably in operation until sometime in the 1860s. In 1860, Balaam Fesmire's son, Alexander, was still living in the area, but Balaam had moved. Also Balaam Craven had moved to a new district in the county. By 1870, the pottery probably was not in operation. By this time Alexander Fesmire had also moved and established a new operation (40HE35).

The 40HE37 pottery site is located on land now densely covered with pine trees. No physical evidence of the site was found at the time of the survey; however, the information provided by informants was very specific as to location.

40HE38

Richard and Riley Garner were the sons of Adam Garner of North Carolina. A.Garner was listed on the 1810 Census for Guilford County, North Carolina. By 1830, Adam Garner was in Henderson County, Tennessee; but, by 1840,Garner had moved to Blount County in East Tennessee (1830 and 1840 U. S. Census, Blount and Henderson counties).

The Garners were back in Henderson County by 1850. Riley and Richard were both listed on the census as potters living near their father Adam. Apparently the Garners continued their wandering life-style because they were not listed in subsequent census schedules for Henderson County. No other records regarding these Garners in Henderson County were found, but the Garner family name is still very conspicuous in the southwestern part of the county. Some of the family may have moved to northeast Arkansas, where there was an 1890s pottery associated with a J. C. Garner (Smith 1972:9).

The pottery site associated with Richard and Riley Garner was located from information provided by Garner descendants. The kiln was formerly situated in an area that has undergone a great deal of change and disturbance due to erosion. A light scattering of brick debris was found, but no sherd sample could be collected. The brick fragments are covered with a heavy coating of salt glaze that would suggest the Garners were producing salt-glazed stoneware.

40HE39 and 40

Mark Mooney was another North Carolinian who settled in Henderson County. Mooney was established here by 1840, and he was listed as a potter on the 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880 censuses for Henderson County.

Mooney built at least two kilns during his more than thirty years of pottery making. Both kiln sites are located in the same general area, and it is not certain which is the older.

Mooney produced salt-glazed stoneware at both sites. Typical vessel forms included crocks, bowls, and grease lamps. He also made tobacco pipes. One marked sherd was found at 4OHE39. The stamp is square in shape with diagonal lines through it that form four triangles. Two of the triangles more deeply depressed than the other two suggesting a stylized "M."

Mooney's pottery was probably out of operation by 1880. On February 2, 1880, Mooney was decreed a lunatic, and the court appointed him four legal guardians (Henderson County Bond and Guardian Book, Vol. A, p. 239).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Auman, Dorothy Cole and Charles G. Zug. 1977. Nine Generations of Potters - The Cole Family. Southern Exposure, Summer and Fall Issue, pp. 166-174.

Beasley, Ellen, 1971. Made in Tennessee. Brochure to accompany an exhibition of early arts and crafts, Tennessee Fine Arts Center at Cheekwood, Nashville.

Smith, Samuel D. 1972. Arkansas Kiln Sites. Field Notes, No. 95, pp. 7-10. Newsletter of the Arkansas Archaeological Society, Fayetteville.