Keeton Store

Dunbar, Tennessee

from the research of K. Donald Keeton

From its early beginning, the Keeton Store at Dunbar has been the activity and social center of the community. Throughout its long and storied existence, it has been the chosen meeting or gathering place for a variety of community functions. It was first a tavern and gathering place. In its early years, in addition to being a country general store, it functioned also as a stagecoach stop, or way station, on the route between Clifton and Lexington. During the Civil War, it served as a recruiting and mustering in center for military personnel. Battle-weary Confederate soldiers stopped at the store to rest and eat a meal prepared by the neighborhood women.

In later years, the store was a polling place where residents gathered on Election Day to cast their votes. At least two gubernatorial candidates, both of whom went on to become Governors of Tennessee, campaigned there. The store building also housed the United States post office at Dunbar, Tennessee, for a number of years and, later, a grist mill was added. The store was considered the community gathering place for local farm families to catch up on news from travelers, send and receive mail and bring shelled corn for grinding into cornmeal for making cornbread, and shopping for most of their needed staples. Finally, an old-fashioned gasoline pump was added about a dozen years or so before the business moved out of the log building and into larger quarters just across the road from the log building store.

The Early Years

Shortly after Dr. Robert Keeton finished his medical schooling in Kentucky about 1820, moved to Tennessee and married his cousin, Catharina Keeton (same last names), in Franklin County, Tennessee, the two of them set out from Franklin County traveling west in a wagon in search of a place to make their fortune and raise a family. They probably joined up with a wagon train along the way as there were numerous families traveling in wagon trains going west about that time in pursuit of their dreams of a better life.

After crossing the Tennessee River at Shannonville (name changed to Bob’s Landing) and arriving about 1825 in the portion of Perry County that later became Decatur County, Dr. Robert Keeton and Catharina scouted the area and found plentiful good, fertile bottom land for farming and abundant rolling timberlands and fresh-water streams for good fishing, hunting and logging. They must have believed they had found the place they wanted to call home. They cleared land, built a house there and he started what became a very successful medical practice. Their first child, a son, John Lawson Keeton, who grew up and became a medical doctor like his father, was born there on May 25, 1826. Dr. Robert Keeton, an educated man with leadership qualities, quickly became active in civic and community affairs, first in Perry County and later Decatur County. He is known to have been in Perry County as early as 1826 when he served on jury duty there, according to Perry County records.

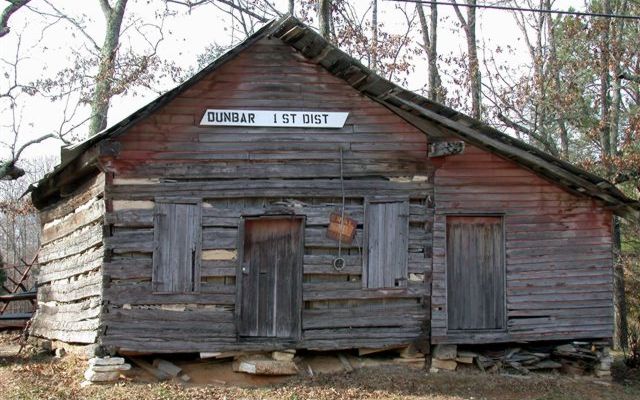

The Keeton Store was built on land that has been in the Keeton family for almost 200 years. Dr. Robert Keeton, the first Keeton to arrive and settle in the portion of Perry County that later became Decatur County, received the land in Land Grant No. 12388, dated August 26, 1851, recorded in Book 7, page 288. The building was a simple, yet impressive, 19th century hand-hewn log design structure with a wood-burning stove in its center.

There is an oral family tradition, as told to Kenneth Donald Keeton (b. August 6, 1934), by his father, Bedford Benard Keeton (b. September 19, 1896; d. March 4, 1975), to whom it was told by his father, Robert Forrester Keeton (b. August 13, 1848; d. January 2, 1911), to whom it was told by his grandfather, Dr. Robert Keeton (b. 1799; d. June 8, 1858), that he, Dr. Robert Keeton, had staked out and laid claim to the said tract of land on which the store stands as early as the 1830s when it was still pretty much a wilderness area and the roads were little more than narrow paths or trails tramped out by the buffalo herds. The Chickasaw Indians had moved out of west Tennessee only about a dozen years or so earlier, significantly calming fears of ambush or attack and freeing up a vast area of land for resettlement by white families.

The oral family tradition referred to above places the date of construction of the old log building store and tavern in the 1840s, which coincides closely with the startup of stagecoach service through the community--before 1845--as well as the formation of Decatur County, also in 1845. Furthermore, after examining the original construction, including the notches in the logs, the nails and other features, it is also the opinion of Michael Thomas Gavin, preservation specialist for the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area, administered by the Center for Historic Preservation at Middle Tennessee State University, that the original structure was built in about the 1840s.

Someone once said the three most important considerations when starting a new business were: Location, Location, and Location. The store was built on a site that became the focal point of the community. It was a site with easy access and high visibility. The store stands alongside the stagecoach route at the intersection of the old Stage Road and Dunbar Road--roughly half way between Clifton and Scotts Hill. It is a convenient location for not only a tavern and a country general store but also a community gathering place or activity center. The log building store is conspicuously visible at the top of the “T” formed by the intersection of the roads where present-day Dunbar Road butts into Highway Tenn. 114, formerly known as Stage Road. As pioneer families arrived and settled in the area, they built their houses and established their farms surrounding the store.

Describing the store as a cracker-barrel type store because of the wide variety of merchandise sold there, Beatrice (Mrs. A. H.) Taylor said it was originally called Hermitage, possibly in honor of The Hermitage, the Nashville, Tennessee, home of Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States (1829-1837). Mrs. Taylor (b. December 2, 1898; d. October 3, 1985), author of an article titled “Tales of Old Days are Recalled in Colorful History of Dunbar”1 and published in The Lexington Progress, Lexington, Tennessee, newspaper on August 1, 1958, was a respected Decatur County historian and longtime resident of the Dunbar community. She was born in the Dunbar community and received the available schooling there. Her home was just a short, 10-minute walk from Keeton Store. Her parents and grandparents had lived in the Dunbar community for several years before she was born.

In addition to the usual items sold in a country general store, which already included just about every necessity of a farm family, there were also occasional special sales such as when the annual shipment of women’s colorful spring hats loaded with flowers, chiffon and ribbons and the latest dress-making fabrics arrived. There also was a tavern and bar in the store building in the early days. Hard times fell on the community after the Civil War. The bar business went away and the owner declared “done bar.” The phrase caught on and that, according to the legend, is how Dunbar got its name.

In colonial America, people went to their village taverns for all sorts of reasons such as mailing a letter, getting legal advice, having a troublesome tooth pulled, or even starting a revolution. They could also eat lunch or get a haircut and shave. A typical colonial tavern was much more than just a place to quench a thirst. It was usually the only public building in town unless that town happened to also have a courthouse. The combination of a general store and a tavern under one roof created a virtual colonial era shopping mall. Some colonial taverns even provided space for church services, business meetings and school classes. The colonial tavern was literally the town’s center.

The American Revolution, arguably the most important event in the history of the United States, was started in a town tavern. Meeting in secrecy on April 12, 1776, at The Sign of the Thistle, a Halifax, N. C., tavern that no longer exists but a portion of which has been restored and is now known as the Eagle Tavern, the Fourth Provincial Congress of North Carolina voted unanimously to recommend to the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, Pa., that the American colonies (provinces) declare themselves independent and free from British rule. Their recommendation, written in the form of a resolution and later named the Halifax Resolve because of where it was adopted, became the first official provincial action by any of the colonies toward declaring independence from Great Britain. Ultimately, the Continental Congress issued the United States Declaration of Independence on behalf of all of the American colonies in July 1776 and thus the colonies became independent states no longer part of the British Empire.

There is no existing evidence of counseling clients with legal problems or assisting patients with medical issues at the tavern at Keeton Store. However, it is a well documented fact that Dr. Robert Keeton was a medical doctor and he was just the first in a line of several medical doctors in the extended Keeton family, any one or all of whom could have practiced briefly at the tavern. There also is ample proof that Dr. Robert Keeton was appointed and served as legal representative for his family in some major court proceedings.

Judging solely by the tale of the bar shutting down when hard times hit, it is unlikely that the Keeton Store tavern ever achieved either the status or the reputation of a major dispenser of hard liquor. Rather, the tavern’s mission all along was to serve the community in ways such as those referred to in the opening paragraphs of this narrative.

People occasionally gathered at the store for a variety of reasons seemingly unrelated to the store’s core business. One former resident of the Dunbar community, a woman now in her 80s, remembered as a child going with her parents to a community mattress making party under the trees beside the old store. It has been reported that the local housewives sometimes held their home economics demonstration club meetings there. And when the whole community was being vaccinated for polio and smallpox, the chosen location for the people to gather for the mass inoculations was Keeton Store. When the old log building was being dismantled for rebuilding in 2010, a medical syringe, apparently never used, was found in a neat little cylinder-shaped wooden case about the size of a toothbrush travel tube lying on a log high up in the wall.

Syringe found in Keeton Store

The Stagecoach Era

As the Stage Road name implies, a stagecoach route with daily schedules ran in front of the store serving points between Clifton to the east and Lexington to the west, with connections to and from points beyond. It was the first stagecoach route operating in the southern end of Decatur County, according to the book, The History of Decatur County Past and Present, written by Decatur County Historian Lillye Younger2, and quite possibly the first stagecoach route in all of Decatur County.

The stagecoach route followed on or very close to the buffalo paths and for a long time was named, simply, Stage Road. The stagecoach route and way station could have been a significant reason for the store’s location beside the old Stage Road, presently named Highway Tenn. 114.

The stagecoach route was begun before 1845 according to Henderson County Historian G. Tilman Stewart, who, in his book, Henderson County3, recognized that the Lexington and Clifton stagecoach route—the one that ran in front of Keeton Store--was the first stagecoach route serving Lexington. Then in the next paragraph of his book he reported that a stagecoach route between Lexington and Perryville was established about 1845. Therefore, the Clifton to Lexington route, which was the first serving Lexington, must have been in operation prior to 1845. Auburn Powers, in his book, History of Henderson County4, stated that the last stagecoach passed through Scotts Hill in 1870. Keeton Store at Dunbar and Scotts Hill were on the same stagecoach route and, therefore, service most likely ended at Keeton Store in 1870 when service ended at Scotts Hill.

The stagecoaches that passed by Keeton Store were portrayed as some of the best and fastest in the business. G. Tilman Stewart’s book offers this interesting tidbit about the speed and excellent quality of the stagecoach service from Jackson to Nashville, which would have passed in front of and stopped at Keeton Store: “In 1850, I. W. Norweed advertised a reduced roundtrip fare from Jackson to Nashville for $16 or a oneway fare for $9 via Lexington, Scotts Hill, Clifton, Waynesboro, and Columbia in 34 hours. The advertisement concluded with the following sentence: ‘This line is now successful, being stocked with new fourhorse tray, superior teams, and careful sober drivers.’" Tickets for the trip were sold by the Jackson Hotel.

Indeed, stagecoaches were the best and only overland for-hire transportation available in all of Decatur County prior to June 30, 1889, when the Tennessee Midland Railway Company began daily train service between Lexington and the west bank of the Tennessee River at Perryville. Children and teenagers, especially, and probably even grown women and men, must have watched in awe as the stagecoaches arrived and departed Keeton Store. Most of them had never ridden in a vehicle as luxurious as a stagecoach. They probably dreamed of some day being able to get on board one of the stagecoaches and travel to some far away place.

The westbound stagecoach stopped at Keeton Store in the mornings and the eastbound stagecoach stopped there in the afternoons. While the driver dropped off and picked up mail and freight, the passengers had an opportunity to get off the stagecoach, stretch their legs and talk with people, often bringing news of happenings in other parts of the country. Local residents sometimes scheduled their shopping trips to the store to coincide with the schedules of the stagecoaches.

One of the best sources for residents to get news prior to the 20th century was Keeton Store. Local newspapers were almost non-existent. There was no telephone service in the community. Radio and television broadcasts were still several years away. But stagecoach drivers and passengers provided an important communications link between the Dunbar community and the rest of the world.

For a long time—until several years after the Civil War (1861-1865)—one of the main wagon routes between Nashville and Memphis was via the old Stage Road (now Highway Tenn. 114) that runs in front of Keeton Store. Some of the wagons were going east but the majority of them were going west. The early pioneers traveling in covered wagons in wagon trains from North Carolina, middle Tennessee and other eastern origins going west in search of their fortunes passed through the Dunbar community in front of Keeton Store. Mrs. A. H. Taylor reported in her newspaper article that after crossing the Tennessee River at Clifton, some of the wagon trains stopped in the Dunbar area for a week or two to rest and perform maintenance on their equipment1 before continuing on their westward journey.

The Civil War Years

During the Civil War, the store was also a recruiting and mustering in center for local military personnel1 where able-bodied men reported for duty, were sworn in and then marched away for assignment.

The Dunbar community, including Keeton Store, remained relatively unscathed by the ravages of military hostilities during the Civil War. Nevertheless, there were troop movements through the community on Stage Road. There were “barn burning” marauding soldiers prowling the nearby woods and fields. The sound of guns along the Tennessee River could be heard at Keeton Store. There was bickering and there was skirmishing within two or three miles of the store, especially at Nebo Hill on New Year’s Day 1863 when a contingent of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s 1800-man cavalry brigade, the 8th Tennessee Cavalry (CSA), under the command of Colonel George G. Dibrell, moving east on Stage Road met and engaged the enemy, the 6th Tennessee Cavalry (US), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William K. M. Breckenridge, moving south on Decaturville Road (now Highway Tenn. 69).

The combatants’ initial pop-shots bickering, a common military tactic used for annoying and delaying the opponent, quickly escalated into a full-blown skirmish with several casualties on both sides. But it was the sound of the big guns at Shiloh on April 6, 1862 that served as the rallying call for local farmers to stop their working in the fields or whatever they were doing, take up their weapons, mount their horses or mules and go join in fighting the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862).

General Forrest, a Tennessee native, passed through the Dunbar community on Stage Road on at lest two occasions during the Civil War: On December 16, 1862 and again on January 1, 1863. General Forrest’s written report to his commander stated that “In accordance with your order I moved with my command from Columbia on the 11th instant, reached the river at Clifton on Sunday, the 13th, and after much difficulty, working night and day, finished crossing on the 15th, encamping that night 8 miles west of the river. . . .” Their camp that night was at the foot of McCorkle Hill near the Red House Inn, about two miles or so east of Keeton Store. The next morning the soldiers continued to move on Stage Road past Keeton Store en route to Jackson.

About two weeks later, on New Year’s Day 1863, after fighting the Battle of Parker’s Crossroads on December 31, 1862, General Forrest and his troops returned to the river crossing at Clifton via Stage Road, again passing in front of Keeton Store.

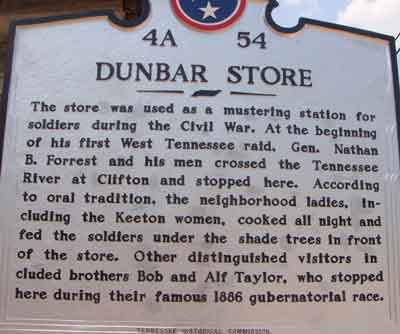

On his way into west Tennessee, General Forrest and troops of his Tennessee Cavalry Brigade stopped under the tall trees across the road from the store to rest and eat a meal prepared by the ladies of the neighborhood. This legend is another oral tradition as told to Betty Gurley Hughes (b. August 12, 1941) by her mother, Vera Maners Gurley (b. October 9, 1909; d. July 16, 1992), to whom it was told by her grandmother, Julia Sophronia Keeton Maners (b. August 9, 1845; d. September 24, 1930), daughter of Dr. John Lawson Keeton and one of the “ladies” who stayed up all night the night before and cooked and prepared food for the general and his tired, battle-weary soldiers. The tradition of the troops stopping to rest and eating a meal under the trees at the store is also recounted in the newspaper article by Mrs. A. H. Taylor1 and is now permanently displayed on the historical marker cast and erected on the site by the Tennessee Historical Commission in commemoration of the Keeton Store and its connection with the Civil War.

According to an oral family tradition passed down through the generations and told to Timothy Bryan Keeton (b. July 10, 1958) by his cousin, William Curtis Keeton (b. November 24, 1903; d. November 1, 1999), to whom it was told by his grandfather, Robert Forrester Keeton (b. August 13, 1848; d. January 2, 1911), that he, Robert Forrester Keeton, sometimes stayed overnight in the store during the Civil War--to deter looting by marauding soldiers—while the rest of the family stayed at the Keeton home located near Turnbo Creek, a mile away. The same oral family tradition states that the laborers on the Keeton farm would hide Dr. John Lawson Keeton’s riding horse during the Civil War to keep marauding soldiers from stealing it. They wanted the doctor to have his good riding horse when he needed to go and take care of the sick people.

Several men from around Dunbar volunteered and served in the Civil War. The stories of three of them are summarized below:

William Alex Tucker (b. 1825; d, April, 1862). Company E, 27th Infantry (CSA). A Rebel from the Dunbar area, Alex Tucker organized a Company (D) called the Decatur County Tigers which formally joined the 27th Infantry at Trenton in September, 1861. Alex was fatally wounded in the first day's fighting at Shiloh (April 6, 1862), with a leg shot off. He lay on the field all night while comrades helped the best they could. The next day he was jolted south in a wagon ambulance as the Confederate soldiers retreated toward Corinth, Mississippi.

After the retreat another Rebel from around Dunbar came home on leave and told Alex's family that he had been critically wounded at Shiloh. At once, Reuben Houston Tucker, 17-year old son of Alex, was started on a mule to try to find and help his father. Nearly 50 miles from home, the boy found the father among the wounded near Corinth and lovingly cared for him the best he could until the father died a few days later. Reuben helped bury his father and then returned home to Dunbar. Soon in the Army himself, neither Reuben back then, nor his popular and able historian daughter, Mrs. A. H. Taylor (Beatrice Tucker Taylor) later, could ever definitely locate Alex's grave. This story is published in the book, History of Scotts Hill, Tennessee by Gordon H. Turner, second printing by Marian Turner Johnson5.

John Washington Tucker (b. January 24, 1831; d. April 29, 1917). There is another oral family tradition as told to Timothy Bryan Keeton (b. July 10, 1958) by his cousin, William Curtis Keeton (b. November 24, 1903; d. November 1, 1999), as told to him by his great-grandfather, John Washington Tucker, that he, John Washington Tucker, was working on the farm when he heard the guns at Shiloh. He stopped working, took his gun, which could have been one of the black powder rifles reportedly built by his blacksmith father, George Washington Tucker, and left for the war. On one occasion an enemy bullet (Minie ball) passed between his ear and his head. He also told of fighting at Chattanooga (there were three Battles of Chattanooga: June 7-8, 1862; August 21, 1863 and November 23-25, 1863). Several years after the war, on January 2, 1881, John Washington Tucker’s daughter, Sarah Emily Tucker (b. February 19, 1866; d. June 15, 1955), was married to Robert Forrester Keeton, the young man who was managing Keeton Store during the Civil War and sometimes stayed overnight at the store by himself to deter looting. John Washington Tucker is buried at Keeton Cemetery.

James Maners (b. March 15, 1843; d. April 24, 1900) enlisted in the Confederate Army on November 25, 1861, and served twelve months in the 51st and/or 52nd Regiment(s) of the Tennessee Infantry. Although he attained the rank of Corporal, he was discharged--honorably, in Company A-51--as a Private for reasons of disability and smallness. Discharge records show he was 5 feet three and three fourths inches tall at the time of his discharge. Several months after the Civil War ended, James Maners married Julia Sophronia Keeton, daughter of Dr. John Lawson Keeton, on January 7, 1866. Julia Sophronia Keeton is the same young woman referred to in a previous paragraph as one of the neighborhood ladies who stayed up all night cooking and preparing food to serve the soldiers at the Keeton Store. This historical information about James Maners is also recorded and published in a Maners family cookbook, Southern Recipes from The Maners Clan.

Other famous people who stopped at Keeton Store include Bob and Alf Taylor when they campaigned for Governor of Tennessee. Robert Love Taylor was Governor of Tennessee 1887-1891 and 1897-1899. Alfred Alexander Taylor served as Governor of Tennessee 1921-1923. Bob and Alf Taylor, brothers—one a Democrat and the other a Republican—both vying for the same political office, ran against each other in 1886 in the gubernatorial campaign known as Tennessee’s “War of the Roses.”

The brothers traveled together, shared rooms in the same hotels, sometimes even slept in the same trundle bed and spoke at the same times and places, one of those places being Keeton Store at Dunbar. Robert Love Taylor, the Democrat and younger brother, won the 1886 election by 13,000 votes. Although Alfred Alexander Taylor, the Republican and older brother, lost the 1886 gubernatorial election, two years later, in 1888, he won Tennessee’s First Congressional District seat and was reelected in 1890 and 1892. Finally, in 1920, when he was 72 years old, Alfred Alexander Taylor won an election for Governor of Tennessee but he was unsuccessful in his bid for a second term in 1922.

Struggles Following the Civil War

Following the Civil War, money was extremely tight in the Dunbar community and elsewhere. Many of the local farm families especially had very little or no cash. Credit cards were not in use during the years the store was in operation. In fact, credit cards for use by the general public with multiple merchants did not begin to become available until a few years after the old store closed. The Diners Club card, one of the first general purpose cards, was started about 1950. It was followed in 1958 by the world wide American Express card. But there was a genuine and growing need for credit in the Dunbar community in the years immediately following the Civil War and, really, right on through the Great Depression years and World War II.

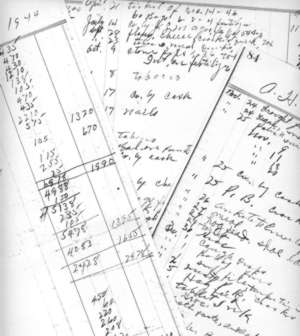

As a service to the community, Keeton Store tried to provide credit to the local farmers who needed credit to tide them over until crop harvest time each year when they could pay their bills. In a typical example, the farmer might offer a milk cow, a wagon and team or even his entire crop as collateral in exchange for a line of credit. The store maintained meticulous handwritten records in a ledger for several years until it switched to a ticket system whereby a handwritten itemized ticket was issued for each credit sale. The customer was given a carbon copy of the ticket and the merchant kept the original for his records.

Once established, credit apparently continued to be available to a customer for as long as his account was in good standing.

The ticket system was still in effect when the business moved out of the log building store and into the cinder block building across the road in the 1940s. There is no evidence that anyone ever defaulted on their promise to pay nor that the store ever foreclosed a mortgage or loan.

After the Civil War, especially, country stores all across Tennessee and probably throughout the South were much more than just places to buy pintos and salted fatback, play checkers and tell war stories around potbellied stoves. Country store merchants were leaders in transforming debt and credit into more of a social obligation and a privilege that should be available to every responsible person, regardless of race, class or gender, and not limited to a business contract available only to white men of means. Those country store merchants were out front in changing communities’ attitudes toward debt and played a huge role in removing the stigma of debt and credit. Without some type of credit arrangement during the difficult years following the Civil War, many local newly freed slaves and farm families might not have survived. An examination of old store ledgers revealed that Keeton Store made credit available to blacks and women as well as white men.

The store also accepted butter and eggs and live chickens in payment for staples such as sugar, coffee, fertilizer and coal oil. Some customers occasionally even referred, affectionately, of course, to the store as the trading post, reminiscent of colonial times. The store owner maintained a chicken coop to house and feed the chickens until they were sold and hauled away to market.

Nearby Schools and Businesses

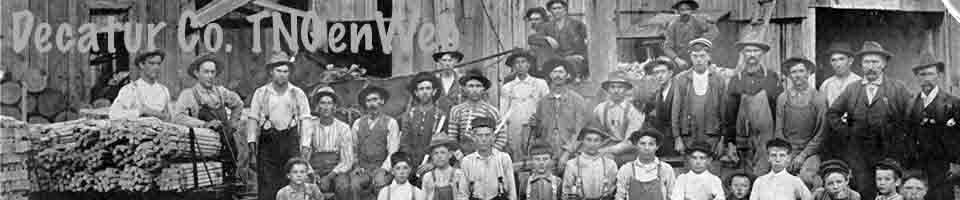

For many of the one hundred years or so that the store operated out of the log building, it was the only commercial establishment in the Dunbar settlement, or community. It was known as both Keeton Store and Dunbar Store and sometimes also referred to simply as Dunbar.

There was a blacksmith shop about 150 yards or so east of the store--assuming the old Stage Road runs east-west--that is believed to have been in operation in about the last half of the 19th century and early 20th century. The shop was last run by Jimmy Mayo. George Washington Tucker (b. July 7, 1801; d. December 15, 1895) was a blacksmith living in the Dunbar area and is believed to have worked in the blacksmith shop and possibly owned it before Jimmy Mayo. George Washington Tucker must have been quite good at his trade of blacksmithing. It has been reported that he probably built several black powder rifles, among many other things, for his customers. George Washington Tucker is buried in nearby Lafferty Cemetery.

About 300 yards or so farther east from the blacksmith shop was a one-room school house. The school was run by Dr. Robert and Catharina Keeton’s daughter, Iantha Adeline Keeton Clardy (b. February 9, 1833; d. November 17, 1919), and her husband, Dr. James Harvey Clardy (b. February 1, 1826; d. January 30, 1871). The school was aptly called Clardy School. A nearby fresh- water spring was the source of cool drinking water for the school. The spring is still active and sometimes referred to as Clardy Spring. The Clardys moved to Texas about 1854 and did not return to Tennessee. James enlisted as a surgeon in Captain D. M. Short’s Company D, 4th Texas Infantry (CSA) on May 23, 1861. James and Iantha Adeline are buried in the Clardy Cemetery at Center, Shelby County, Texas.

West of Keeton Store—again, assuming the old Stage Road (Highway Tenn. 114) runs east-west—about a mile or so up the road, near Brooksie Thompson Road, there was a cotton gin that was in operation in the 1880s and probably longer. It was called Dunbar Cotton Gin6. There is evidence that it was operated by J. J. Lancaster from 1879 until 1888. Mr. Lancaster left a ledger containing documentation of his transactions. The gin was last run by the Clint Brasher family but exactly when it shut down is not known. The gin was steam powered and sat close to the headwaters of Turnbo Creek where it got its water supply.

Union Hall School was located between Keeton Store and Dunbar Cotton Gin. Initially, it was domiciled in a building built for the Farmers Union in 1907. Later, a larger building was built for the school. The one-room, one teacher Union Hall School stayed in it teaching classes through the eighth grade until about the early 1950s when it was consolidated with the Decaturville schools.

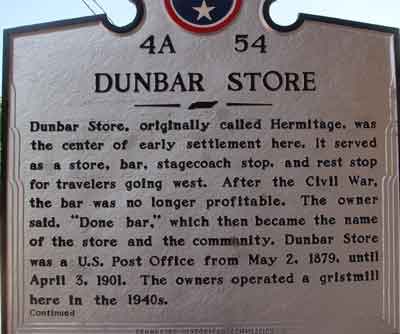

Dunbar Post Office

The official United States post office at Dunbar, Tennessee, resided in the store from May 2, 1879 until April 30, 1901 when it was transferred to and consolidated with the Bath Springs post office. This event is confirmed in a letter dated September 18, 1981 from Thomas G. Hudson, Director, Federal Archives and Records Center, General Services Administration – Region 4, East Point, Georgia, to J. Paul Montgomery, Bath Springs, Tennessee. Residents from all over the community came to the post office to send and receive mail. The front door of the old store still has the letter drop slot where letters were dropped inside 130 years ago. The Bath Springs post office has now been relocated to the new Keeton Store building at Dunbar, across the road from the old log building store.

There was no home delivery of mail in the early years. The store was sort of an unofficial post office even before it became a United States post office and then again after the consolidation with the Bath Springs post office. Rural Free Delivery (RFD) service was begun in the United States in 1896 to deliver mail directly to farm families. But not every household got home delivery even after RFD was begun, due primarily to poor road conditions or distance from the roads. The early rural letter carriers usually made their rounds on horseback, by wagon or some type of horse-drawn buggy. As many as a dozen families still maintained mailboxes at Keeton Store until about the 1950s. Someone from those households usually walked to the store every day to get their mail. The mailboxes were mounted on posts and lined up in a row beside the road in front of the store and serviced by the rural letter carrier from the Bath Springs post office.

The early settlers did not do a lot of letter writing. They were too busy building their houses, clearing the land and raising crops. But there were occasional letters to and from residents of the Dunbar community. Steamboats hauling passengers, mail and freight on the Tennessee River regularly interchanged mail pouches with the stagecoaches at Clifton for points along the Clifton to Lexington stagecoach route.

Some of the new merchandise arriving for Keeton Store was shipped by steamboat before being transferred to stagecoaches for delivery. Other travelers also sometimes brought incoming mail from the steamboats to addressees along the route. They usually either dropped the mail off at Keeton Store or delivered it personally to the addressee. Outgoing mail was handled in much the same way.

Establishment of the Dunbar post office in 1879 with the appointment of Robert Forrester Keeton as its first postmaster brought some needed order and a degree of dependability to the mail service in the community. It was still necessary, however, for Dunbar customers to go to the post office to receive and send their letters.

The 20th Century; Great Depression; World War II Years

For many years, the store was an official polling place where voters gathered on Election Day and cast their ballots. Election Day was also an occasion for a community picnic or a church fundraiser with a food and drinks concessions stand under the oak trees at Keeton Store. The socializing activities provided a reason for families--men, women and children of all ages--to load into their mule- drawn wagons for a trip to the store and spend a full day voting, visiting and picnicking.

Women were not allowed to vote prior to August 1920 when the Suffrage Amendment, the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, was ratified by the required three-fourths, or 36, of the 48 states and became the national law. After having been ratified by 35 states, Tennessee narrowly approved the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, with 50 of 99 members of the Tennessee House of Representatives voting yea. Thus, Tennessee gained the dubious distinction of being the 36th, and last, approving state needed for the amendment to become the law of the land. To its credit, however, Tennessee had already, in 1919, granted women the privilege of voting in Presidential elections only. The Tennessee legislature’s favorable vote on the Constitutional Amendment on August 18, 1920 cleared the way for the United States Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the privilege to vote in all elections. For the record, the other 12 states ultimately ratified the amendment, Mississippi being the last, in 1984. Alaska and Hawaii were not states when the amendment was ratified.

Sometime during the Great Depression years (from about 1929 to about 1939), Bedford Benard Keeton, who owned and was running the store at the time, built a lean-to shed onto the east side of the log building store and added a grist mill—the kind of mill that produces stone-ground cornmeal for baking cornbread. The grist mill proved to be a hugely popular and successful investment.

Out of economic necessity, many farm families were eating cornbread regularly for dinner and supper and frequently even for breakfast, too. Times were tough everywhere. There were national food shortages and government rationing of some food products such as meats, sugar and coffee, especially during the Great Depression and World War II. Families were eligible to receive an allotment of orange and blue stamps determined by a government formula. With the stamps a person could purchase the specified amount of a rationed item. Without the stamps, however, he could not buy the rationed commodities from a store. Merchants were required to keep detailed records of sales of the rationed merchandise.

Grist mill customers from all over the county flocked to Keeton Store with their sackfuls of shelled corn for milling. Mainly, they came on horseback and in wagons but there were also some cars and pickup trucks. Saturday was the designated grinding day and the mill usually was running continuously from early morning until night.

Since the designated milling day was Saturday and not a school day, it was not uncommon for the entire family to load into the wagon and make the trip to the grist mill. The women enjoyed shopping and visiting in the store while the men usually watched the milling process and the children played games outside. Old timers remember one customer in particular, Mr. Elsie Casey, who had gained the reputation for being the last customer of the day. He always arrived at the grist mill with his sack of shelled corn just as daylight was fading into darkness. Mr. Casey very graciously helped out by holding a kerosene lantern so the miller could see what he was doing as he went about his work adjusting the grinding wheels, regulating the rate of flow of the corn and testing the texture of the cornmeal.

The grist mill was powered by an Allis Chalmers Model B tractor that was used on the Keeton farm during the week. There was a belt attachment running from a pulley on the tractor to a wheel pulley on the main shaft or axle of the grist mill. Before starting the grinding, each customer’s corn was carefully measured and a portion of it scooped out and put into a toll barrel as the “miller’s toll,” or percentage of the corn, for his compensation. The toll corn collected at the mill probably was fed to the miller’s chickens or livestock as there were always plenty of animals on the farm. The miller then poured the customer’s corn into a cone- shaped hopper above the belly, or grinding chamber, of the mill where the actual grinding took place. He attached the empty sack to a chute to receive the meal when it was ready.

The idea of a miller’s toll is not new and it did not originate with the grist mill at Keeton Store. In fact, it did not even originate in America. The custom of a miller’s toll was practiced at grist mills in Great Britain and perhaps other countries long before the first English colonists sailed to America and dropped anchor on May 14, 1607 at the place in Virginia they named Jamestown in honor of their king, King James of England. The very early grist mills were almost always supported by farming communities and the millers received the miller’s toll in lieu of monetary wages.

Apparently, both the miller and the customers at the Keeton Store grist mill liked the novelty of the miller’s toll. With the mill running just on Saturdays at Keeton Store, the miller’s toll could not by itself have been a huge profit maker for the miller. Likewise, a few scoops of shelled corn were not a big strain on a farmer’s food budget. One old timer remembered that the miller’s toll at the Keeton Store grist mill was one-seventh of each customer’s grain. That translates to eight pounds out of a 56-pound bushel of shelled corn. The cash value of eight pounds of corn during the Great Depression years and World War II is not known. The real payoff came in the form of goodwill, community service and more happy shoppers in the store.

When finished with the preliminaries, the miller then activated a shaker, or vibrator, that started gently shaking corn through a controlled orifice at the bottom of the hopper cone letting it spill slowly into the grinding chamber below where the kernels were cracked, crushed and rubbed between large stone wheels turning about 120 rpm in a spinning and grinding motion until the desired texture of meal was achieved—thus the term stone-ground cornmeal. The meal was then screened out of the grinding chamber into the exit chute, or trough, leading back into the customer’s sack attached to the mouth of the chute. Thus the customer’s sack was refilled with cornmeal ground from the same grain he had brought to the grist mill minus the miller’s toll. Satisfied customers used to say “Mr. Bedford” had a special knack for grinding the corn just right for cornbread— not too fine like flour and not too coarse like grits. Old-timers would tell you that stone-ground just tasted better.

Bedford Keeton continued to run the grist mill for a while after the old store closed and the business moved across the road into a new cinder block building in the late 1940s. Before he retired, Bedford Keeton taught his youngest son, Bryan Edison Keeton (b. June 15, 1936), the art of milling and Bryan kept the grist mill business going for several more years. When the grist mill operation was finally discontinued the lean-to shed was dismantled and removed from the log building and the grist mill itself is now stored at a separate location.

Another popular addition to the store’s line of merchandise during the Great Depression years was a gasoline pump to accommodate the growing demand for gasoline by local farmers as well as passing motorists. It was a Standard Oil Company Esso (now known as Exxon or ExxonMobil) gasoline pump and it stood in front of the store slightly left of the store’s entry door--as one faces the store. There was enough space for a car to go between the store and the pump and also room for a car on the side of the pump away from the store without hanging over in the road.

Dorothy Keeton Blankenship pumping gas

The pump was manually operated—there was no electricity anywhere in the Dunbar community in the 1930s and first half of the 1940s. Pumping in a back and forth motion on a baseball bat size handle attached to the pump, the operator pumped the gasoline from an underground storage tank into a measured 10-gallon glass bowl on top of the pump. When the bowl was full, the operator released the gasoline from the bowl by squeezing a nozzle, allowing the gasoline to flow by gravity through a hose and the nozzle, similar to the nozzles we use today, into waiting cars and trucks and farm equipment. Customers were not expected to pump their own gasoline—store personnel pumped it. Prices were as low as twenty cents a gallon in the 1940s. Instead of buying a “fill ‘er up” tank of gasoline, most customers chose to get either five gallons (a dollar) or ten gallons (two dollars). The first electric gasoline pump at Keeton Store was installed at the new building across the road from the old store.

The store received its gasoline supplies by truck from a Standard Oil Company distributor at Lexington. Deliveries were made to the store about once or twice a week or as needed.

One more customer-pleasing addition was an icebox drink cooler. It was added sometime about the 1930s when ice delivery from the ice plant in town became available at Keeton Store. The icebox was conveniently placed in the center isle of the store pretty close to the front door. It was a wooden box with tin inner- lining about the size of a large office desk and was kept well stocked with bottles of ice-cold soft drinks. The price was five cents. The customers liked it. It was the first time they could buy cold drinks at the store. Some of today’s old timers would tell you that drinks tasted better back then when they were sold in glass bottles and chilled on big blocks of ice. During winter months when ice was not needed, the drinks were still kept in the drink box to protect them from freezing and bursting the bottles.

Dr. John Lawson Keeton, the eldest son of Dr. Robert and Catharina Keeton, was an early owner of the store. But he had other business interests, as well. Following in the footsteps of his physician father, Dr John Lawson Keeton completed the necessary schooling and also became a medical doctor. He maintained an office at Swallow Bluff, a thriving river landing settlement along the Tennessee River, several miles from Dunbar. In addition to his office practice, he made house calls on horseback throughout the county. He also enjoyed spending as much time as possible at the farm where he sometimes worked in the fields side by side with the laborers.

Management of the store was delegated to other family members. Dr. John Lawson Keeton’s oldest son, Robert Forrester Keeton, with help, no doubt, from his step-mother and his siblings, was running the store during the Civil War and continued to do so until sometime in the 1890s. In addition to running the store, Robert Forrester Keeton also served two terms—almost seven years total--as postmaster of the Dunbar post office. He was the first postmaster of the Dunbar post office, serving from May 24, 1879 until April 15, 1881. Later, he was appointed again and served from February 14, 1889 until December 21, 1893. The post office was domiciled in the store building during that time.

In the 1890s, Robert Forrester Keeton sold half interest in the store to his neighbor, W. D. (Billy) Johnson, Jr., who lived beside nearby Turnbo Creek. They then called the business Keeton & Johnson. A little later, Mr. Johnson bought the other half interest and ran the store by himself for several years before selling out to Hence Ray.

Mr. Hence Ray had run the store for only a short time when, about 1925, Robert Forrester Keeton’s youngest son, Bedford Benard Keeton, bought it. He had recently returned home from duty in World War I (1914-1918). After that, except for about two years when Walter H. Lafferty and J. Leonard Magers owned and ran it, the store has been in the Keeton family and is now referred to alternately as Keeton Store and Dunbar Store. The business moved into a new, two-story cinder block building across the road in the 1940s. The top floor of the new building was built to house the Masonic lodge. The Masons and Eastern Star still hold their meetings there regularly.

There was no electricity at the store or for that matter the whole community until after World War II when the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) brought electricity to the entire region. TVA had built a hydroelectric dam at Pickwick Landing on the Tennessee River in the 1930s and after World War II began an aggressive expansion program bringing electricity to surrounding communities. Before electricity was turned on about 1946, the store lights were kerosene lamps or lanterns hanging on the walls. From the time it first opened in the middle of the 19th century until it was finally closed, the log building was heated by a wood- burning stove located near the center of the store. The men customers— smokers, in particular--seemed to enjoy their camaraderie more while they sat on empty wooden nail kegs spaced around the stove, nursing hand-rolled cigarettes between their nicotine-stained fingers and stoking the fire in the stove on cold winter days.

About the author:

K. Donald Keeton was born and grew up in a log house across the road from the old Keeton Store. Well, actually, by the time he came along—he is the seventh of nine children in his family—the house that started out after the Civil War as a pretty typical 19th century Tennessee log house with two large rooms, or pens, two fireplaces and a dog trot in between, already had several additions just to accommodate the rather large family. The add-ons included a kitchen, dining room, bedroom, front room and porch. His birthplace, nevertheless, was and still is a log house. The two hand-chiseled limestone chimneys are still visible from the outside but the log walls are hidden behind newer construction. When he was growing up on the Keeton farm, he had a good view of the log store building from his front porch. He has been able to draw on his personal experiences as he researched and penned the Keeton Store article.

Born in the midst of the Great Depression, Don attended the one-room Union Hall School at Dunbar through the seventh grade, then was transferred to the Decaturville schools and ultimately received a diploma at Decaturville High School. He has now lived away from Dunbar and Decatur County for more than six decades but still cherishes many fond memories of growing up working and playing in the fields and at the store at Dunbar. To paraphrase a familiar old saying: The vicissitudes of life may take a boy away from home but they can't take away his memories.

Footnotes:

1Article titled “Tales of Old Days are Recalled in Colorful History of Dunbar” by Mrs. A. H. Taylor published in The Lexington Progress, Lexington, Tennessee, August 1, 1958 and also published on the Internet at http://www.tnyesterday.com/yesterday_decatur/dunbar/dunbar_history.html

2The History of Decatur County Past and Present, by Lillye Younger, also published on the Internet at http://www.tnyesterday.com/books/younger/y05.html

3Henderson County, by G. Tillman Stewart, also published on the Internet at http://www.tnyesterday.com/books/stewart/first_decades.html

4History of Henderson County, by Auburn Powers, also published on the Internet at http://www.tnyesterday.com/books/auburn/ap-c14.html

5History of Scotts Hill, Tennessee, by Gordon H. Turner, second printing by his daughter, Marian Turner Johnson.

6Ledger from Dunbar Cotton Gin - 1879 from the research of Jerry L. Butler at http://www.tnyesterday.com/yesterday_decatur/dunbar/cotton_gin/GIN.html

Keeton Store is being restored

Restoration of Keeton Store - 2011

Front Door to Keeton Store with Letter Drop Slot

Dunbar Store Historical Marker

Following restoration of the Keeton Store at Dunbar, a Tennessee Historical Marker was placed at the store and dedicated on May 26, 2012.

|  |