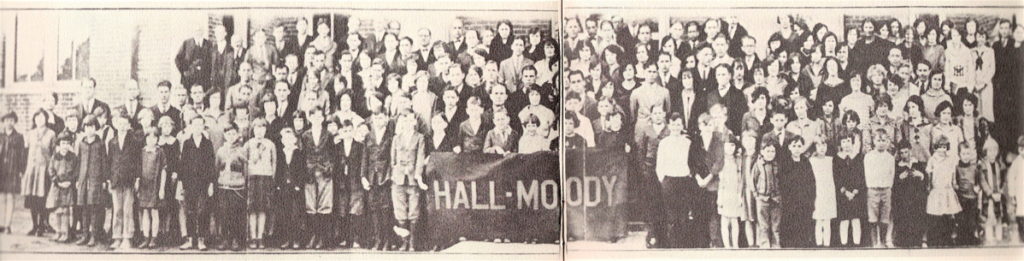

Hall-Moody Institute – Students & Faculty 1926.

.

Memories from the past….

Predictably rigid decorum was maintained at Hall-Moody. “Desent” dress was required and, as one 1907 almna recalls, “teachers did not allow any sweethearting in school.” Catalogs in the mid-twenties specified that “young men and young women are not allowed to waste time by constant association.”

During the Hall-Moody era there wer no paved roads into Martin, and until the twenties, Martin streets were gravel or cinder. In the last years of Hall-Moody Junior College, some of the main streets in Martin were paved. Few if any students owned automobiles, and the few teachers, like Dr. Barrett, who had them, generally had what one alumnus calls “rattletraps.” Even after Mechanic Street was extended up past Lovelace Hall, there was a big mudhole – between the present Home Economics building and the Woman’s gym – from which domoitory boys would routinely have to extricate motorist. As late as the twenties, students often drove teams [of horses or mules] to school, parking them in the field across from the Administration building. Those who didn’t take buggies or wagons often used the train to get in and out of Martin. The Martin depot, where coaches let off returning students, was a weekend gathering spot.

On a Sunday or Monday afternoon, one could walk down Mechanic Street, past homes still standing, passing the Baptist Church on the left and then the Martin Public School on the right, turn up Lindell as far as the Post Office (now the Library), see who was arring, then perhaps drop down by the Railroad Park, a $15,000 investment and the pride of Martin in the twenties, with its “splendid rest room for ladies and children.” One 1907 alumna recalls getting home, but not often, by riding the caboose on a freight train to Sharon, TN.

The Academic Program

At first, given the limited course offerings, everybody at Hall-Moody Institute took more or less the same things, but the variously differentiated degrees — A.B., B.S., B,L., and L.I. — were awarded after 1904. Most early students earned the A.B. or B.S. Business graduates began to be recorded after 1903, as did recipients of diplomas in special areas such as Expression. Expression and Oratory — like the language, classics, and Bible courses — were staples from the first. As one catalog remarked, “The voice can be changed to better, deeper tones and it should be a pleasure to cultivate it.”

The academic program was boosted by Mr. Parker’s $1,000 gift in 1912 for library books. By 1913 there were 4,000 “well-selected” volumes. The 1915 catalog warned that the library was “not a place for social enjoyment or idle pastime, nor our laboratories for useless experiments.”

Promotional literature throughout Hall-Moody’s history, in fact, emphasizes the seriousness of academic pursuits — and the fruitful results that serious application brings. The study of theology was thus offered to the minister to “help him to help himself and thereby help others.” Studying music promised to lead the student “to be able to appreciate fully a part of heaven which God has put on earth.” Band work was said to lead to “remarkable development of the chest and muscles of the neck and face” — and to be better for “weak chests” than athletics. Art had practical significance in “architecture, manufactury, … home decoration.” Particularly until World War One, Hall-Moody programs mirrored Baptist orthodoxy, the work ethic, and the lingering Emersonian belief in the capacity of ordinary people for self-improvement and transcendence.

In 1915-16 the Preparatory Program was sorted out from other courses of study, and received state accreditaion by requiring the 15 Carnegie units (10 prescribed, 5 elective) also mandatory in public high schools. Four years of Latin was a standard feature. The junior college curriculum after 1917-18,also standardized to lead to the associate degree, offered variety but emphasized basic courses. Tuition was $25 a term in 1920.

The Hall Moody Faculty

“THE TEACHERS were in control,” says one 1911 Hall-Moody graduate. Another alumnus, still disgruntled, recalls their “big ‘I’ little ‘you’ ” attitude (and says most came to Hall-Moody because “other schools wouldn’t have them”). But many others remember teachers fondly: Mrs. Burke, for her patience; Miss Hall for her “marvelous stories”; Dean Witherington for his singing in chapel; Miss Skinner for her “inspiring classes”; Miss McColloch for her “unique personality”; Mrs. Davies, who required and “exact” Latin pronunciation, for her “brilliance,” for her ability to inspire “a love for good literature”; Professor Robinson for his “wisdom and gentle nature”; and Mr. Barrett, the former New York Giant pitcher, for his “strange commingling of humor, philosophy, pathos, and good morals.” One graduate remembers the spring night in 1910 when Mr. Robinson took his astronomy class up into the bell tower to watch Halley’s Comet. Another says, “I can still hear Dr. W. J. Davies call the roll in his long drawn out manner.”