THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IRON INDUSTRY

IN THE UPPER BUFFALO RIVER VALLEY

[Note: This paper was delivered before a joint meeting of the Lewis County Historical Society and the Wayne County Historical Society at Oak Grove Methodist Church, Lewis County, Tennessee, September 10, 1989.]

The history of the development of the iron industry in the upper Buffalo River Valley spans over one hundred years, from about 1816 until the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929. For the purpose of this paper, two particular areas of iron manufacture will be discussed. The first is what was known in the twentieth century as the Napier Iron Works, which traced its origins to a small forge in operation in the 1810’s. The second area of concentration will be the Allen’s Creek furnaces. These furnaces occupy only a short period of the history of the area, but were part of a much larger and grander operation than the Napier Works.

The first iron producing operation on the upper Buffalo was that of John McClish, a Chickasaw Indian. From available records it appears that McClish operated a small forge on either Buffalo River or Chief’s Creek about 1818. This forge was located on property McClish had obtained as part of the Chickasaw Session Treaty of 1816. The treaty granted to McClish and his heirs in perpetuity, 640 acres of land, or one square mile, at the point where the Natchez Road crossed the Buffalo River1.

It is not known what type of forge was in operation at this site. Nor is it known what types of iron or iron products were produced. It is probable that McClish used the forge to make cast products such as kettles and pots, and may have also produced rod or bloomery iron for sale in Natchez and Columbia. The production could not have been great since no reference is made to any mining operations in the area. The ore used by McClish was readily available in large quantities on the top, or near the top, of the ground.2

By 1822, McClish was experiencing financial problems and the sheriff of Lawrence

County, Tennessee sold portions of McClish’s lands to satisfy judgements against it. It appears that at this time McClish leased his iron works, or the lands on which they stood, to John Jones, David Steel and Thomas Steel. Reference is made in Lawrence County, Tennessee Court minutes of a petition from these men at this time to condemn 3000 acres of worthless and unclaimed land for their iron works located on the southwest corner of McClish’s land. This may have been the “Hed’s Old Works” referred to in 1827.3

The on 3 July 1827, McClish sold 160 acres, which included the “Hed’s Old

Iron Works” to John Catron and John C. McLemore who had earlier bought out the heirs of Jones, and the interest of the Steel’s. McLemore sold his interest to Lucius J. Polk who with John Catron and Catron’s brother, George, entered into a partnership known as the Buffalo Iron Works. George Catron, familiar with iron production, became manager of the works. By 1828, John Catron was the sole owner of the operation. George Catron died in 1828, and Polk sold his interest to John Catron in 1827. At this time Felix Catron became manager of the works.4

The Cantrons managed the Buffalo Iron Works for five years. It is not known whether or not the operations were successful or would have been. The “Biddle Panic” of 1833, brought on by the dissolution of the Bank of the United States by President Andrew Jackson, brought an end to the management of the works by the Catrons. John was forced to sell the works to his son, John Jr, and George F. Napier. They were unable to obtain funding for the purchase due to the unsettled financial conditions and Napier had to get brother, Dr. E. W. Napier, to co-sign the loans from the banks.5

The Buffalo Iron Works were apparently inactive at this point. In 1836, Napier announced that he was going to completely rebuild the works. However, again financial panic closed the operations before the new furnace could be brought into blast. The company underwent several reorganizations and was finally taken over by Dr. E. W. Napier.6

In 1845, Dr. Napier gave his nephew, William C. Napier, one-half interest in the Buffalo Iron Works. At this time, it appears the works had been idle for some time as the younger Napier set about rebuilding the furnace stack and improving the operations. When Dr. E. W. Napier died in 1848, William C. Napier became the sole owner.7 According to J. B. Killebrew, production during this period had been about 20-23 tons of pig per day when in blast.8

The Buffalo Iron Works now became known as the Napier Iron Works. L. G. W. Napier, possible brother of William C., is listed in the 1850 Lawrence County, Tennessee census as iron maker and was probably in charge of the operations.9 The works seems to have continued throughout the 1850’s and into the early 60’s. In 1860, William C. Napier himself was listed in the Lawrence County, Tennessee census as “Iron Monger” and had probably taken direct control of the operations.10

We have no record of the activity of the Napier furnace during the Civil War. The

furnace is prominently marked on the military maps made during the war, but no indication is made as to whether or not the furnace was in use, abandoned or destroyed. Gen. Buell’s army passed by the furnace in April 1862, and Gen. Hood’s army passed the neighborhood in November 1864. Neither makes any reference to the operations.

At this point the furnaces were located in Lawrence County, Tennessee as a result of the repeal of the act creating Lewis County. Maps of the period show the iron works to be on the south side of Buffalo River.11

Following the war, the furnace seems to have undergone extensive repair and was put back into operation. The following excerpt from Tennessee’s Western Highland Rim Iron Industry, complied by Samuel D. Smith, Charles P. Stripling and James M. Brannon in 1988, gives a description of the furnaces at Napier.

The furnace is reported to have been again repaired in 1873, and at that time the single stack was 33 feet high by 9 feet across at the bosh, dimensions suggesting an old-style furnace stack. The forge was refitted in 1879-80, and consisted of a water powered operation with four fires and two hammers, with an annual capacity of 600 net tons of charcoal blooms.12

During the 1870’s the works appear to have been leased by Napier to other operators. Although later reports indicate that during the 1880’s the furnace and forge were abandoned or inoperative. In 1885, all the Napier Furnace lands were included inside the boundaries of Lewis County.13 By 1891, the company was again reorganized and the new owners, E. C. Lewis and J. Hill Eakin, under the name, Napier Iron Works, built a new furnace.14

In 1891, a new stack 60 feet high by 12 feet across at the bosh was built and was put into blast in February 1892. This is evidently the furnace located about one-half mile northwest of the original operation. The old hillside furnace was permanently abandoned at this time and the village of Napier was established.15

During the 1870’s the iron blooms and pigs were carried by wagon to Mt. Pleasant, Tennessee where they were transferred to the railroad for shipment. Several years later, the railroad was extended to Carpenter’s Station and finally in 1894, the Nashville, Florence and Sheffield Railroad was granted a right-of-way through the Napier properties and the line was extended to the furnace.16

The new furnace was remodeled in 1897 to use coke instead of charcoal and operated in this capacity producing foundry pig iron until 1923 when it was blown out for the last time. In 1927, a corporation was formed under the leadership of W. R. Cole, a former company president, but plans for the revitalization of the Napier Iron Works were not realized due to the onset of the Great Depression. The furnace was dismantled about 1930

for salvage material.17

According to Mr. Lindsey, President of the Napier Iron Works in 1912, the Napier

furnace was producing about 100 tons of #2 foundry pig per day.18

—————-

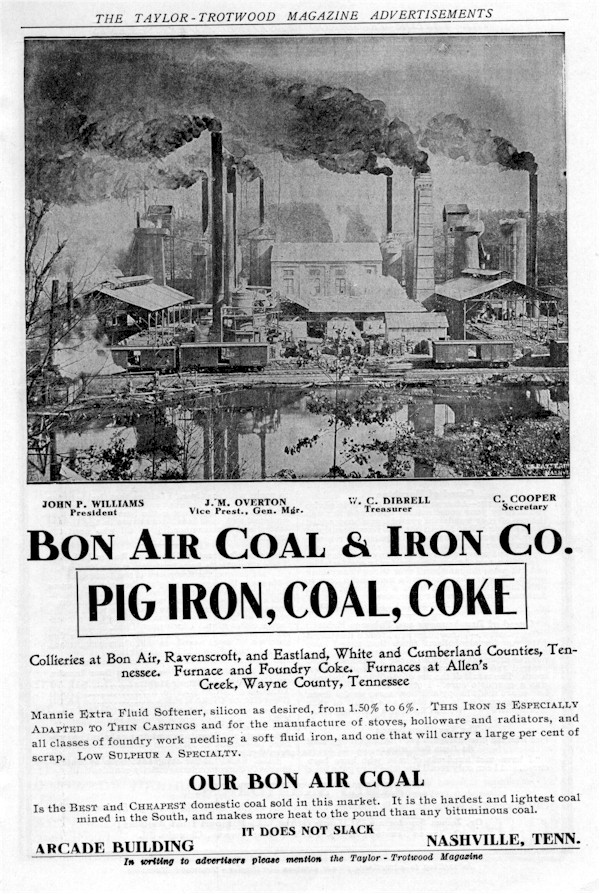

Ad for the Bon Air Coal & Iron Company which appeared in “The Taylor-Trotwood Magazine” February 1907

The second of the iron furnaces in the upper Buffalo River valley was the Allen’s Creek furnaces. This operation was started in 1891 by the Southern Iron Company as a mining operation. Through the machinations of the Southern Iron Company, the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railroad built a trunk line from Shubert in Lewis County, Tennessee to Allens Creek in Wayne County, Tennessee. The main interest at first seems to have been mining ore. But in 1892, construction was begun on two furnaces. These were built from materials and machinery salvaged from two abandoned coke furnaces in west Nashville. Called Mannie #1 and Mannie #2, the #1 furnace was blown in on 22 April 1893.

But before #2 could be brought into blast, the financial panic of 1893 made the company insolvent and operations ceased.19

In 1895, the assets of the Southern Iron Company were bought by the newly established Buffalo Iron Company of Nashville. The new company refurbished Mannie #1 and blew in #2 in 1896.20

During the period from 1892 until 1902, the furnace, when in operation, used charcoal for fuel. At one point, with both #1 and #2 operating, it took two acres of timber a day to furnish charcoal for the furnaces.21 The process was expensive and required many hands to cut the timber, saw it to length for the ovens, fire the ovens and then remove the finished charcoal. A review of the 1900 census for this area reveals that over 50% of the hands were involved in the timber operation.22

In 1902, the Bon Air Coal & Iron Company took over the assets of the Buffalo Iron

Company, which included the assets of the Warner Company in Hickman County, Tennessee. In exchange for $730,265.94 in preferred capital stock and $730,264.94 in common stock, the Buffalo Iron Company transferred all its assets, contracts, lands and its indebtedness to the Bon Air Coal & Iron Company.23

At this point the furnaces at Allens Creek were changed from charcoal to coke fired furnaces. From an economic standpoint, this was a more profitable arrangement since the Bon Air company owned coal mines at Bon Air, Ravenscroft and Eastland, Tennessee. When necessary they also bought coke from the Virginia coal fields.24

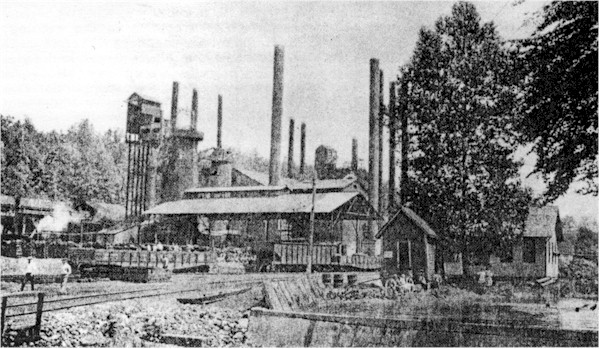

The Mannie furnaces at Allens Creek, 1923. Reproduced from the Tennessee Division of Geology Bulletin 39, Plate 29.

Then in 1917, the Bon Air Coal & Iron Company was reorganized as the Bon Air Coral & Iron Corporation with Mr. William J. Wrigley as chairman of the board, James R. Offield, president, Wm. J. Cummins of Nashville as vice-president, John Bowman, treasurer, and Frederick Leare as secretary. Mr. Wrigley, the principal financier in this reorganization was the founder and president/chairman of the board of Wrigley Chewing Gum Company of Chicago. Bowman, president of the Biltmore Hotel chain in New York was the secondary financier.25

Mr. Wrigley’s perception of the problem with the iron industry was summer up in a letter he wrote to J. H. Patrick of Nashville on 5 August 1918:

Some of your descriptions have caused me to laugh for I know how true they are; especially what you say about the Iron Division. First, they are long on coke and short on iron, and then long on coke and iron and short on limestone; then, they are short on all three.26

Because of his sizable investment in the Bon Air operations, Mr. Wrigley made an

inspection tour of the operations in 1917. He arrived by private railroad car in

Collinwood, Tennessee from Nashville, Mr. W. M. Cummins in tow. While in Collinwood, they toured the Bon Air lands and operations west of the town. Then on the second day of the visit, they drove to Waynesboro where Mr. Wrigley delighted the children on the square by passing out free chewing gum. Returning to Collinwood, there was a grand reception in the evening at the Highland Inn, hosted by the Highland Inn Country Club. The following day, the entourage boarded Mr. Wrigley’s private care for a tour of the Allens Creek and

Lyles, Tennessee operations before returning to Nashville.27

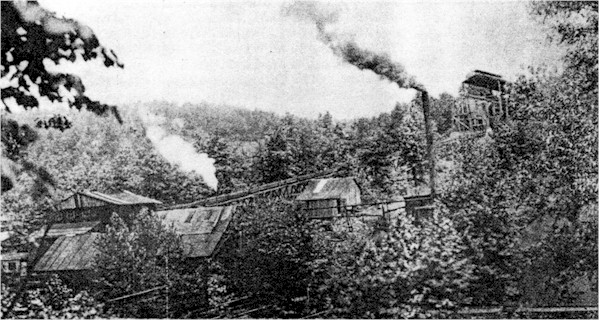

Ore washer at the mines of the Bon Air Coal & Iron Corporation, Allens Creek, Lewis County (formerly Wayne County) Tennessee, 1923. Taken from Tennessee Division of Geology Bulletin 39, Plate 28.

The furnaces at Allens Creek continued intermittent operation until 1923. From 1920 to 1923, only one stack was in blast. The company underwent reorganization in 1920. In an attempt to remain competitive, the corporation induced the state legislature to change the county line between Wayne and Lewis Counties so that the Allens Creek operations were placed in Lewis County. This occurred in 1924. But all attempts at revitalization failed; the furnaces were dismantled in 1926 and sold for scrap iron.28

The biggest problem associated with the iron industry in the Buffalo River valley, as well as elsewhere on the Western Highland Rim, was the lack of capital to finance the operations. To build and operate the furnaces required large amounts of money which was not always readily available. Prior to the Civil War, the only means of obtaining this capital was in loans from banking institutions and in partnerships of monied people. The limited liability stock company had not generally come into use prior to the war.

This practice of partnerships and loans was fraught with problems. Frequent financial panics forced calls on loans and often forced the dissolution of the partnerships. Each time the iron works were the first to feel the effects of the panics.

The Civil War practically destroyed the industry in the Western Highland Rim. Prior to the war, much of the labor had been supplied by slaves, usually leased from the planters or their estates. The war and the subsequent emancipation of the slaves, eliminated a pool of cheap labor. Attempts to rebuild following the war were often met with further economic setbacks. The Panic of 1873 for example resulted in a four-year long depression which wiped out most of the operations.

Another problem facing the iron producers in the upper Buffalo River valley was

transportation. Prior to the 1890’s their ores had to be hauled to the furnace or forge site by wagons; the finished product, either pigs or blooms, had to be hauled, again by wagon, to either the railhead at Mt. Pleasant, Tennessee or to the nearest river port, Clifton, Tennessee. The building of the spur lines from Summertown to Napier and from Centerville to Allens Creek eliminated most of the transportation problems. But it was simply too late; by this time, the rich ore fields in Minnesota and Wisconsin had eliminated the need for the poorer quality iron produced at Allens Creek and Napier.

There is little doubt that the iron industry play a significant role in the development of the upper Buffalo River valley. There is also little doubt that financial instability and the availability of higher grade ores spelled doom for the iron industry in the upper Buffalo River valley.

____________________

Footnotes:

1. Phelps, Dawson, “Stands and Travel Accommodations On The Natchez Trace”,

unpublished. manuscript, Natchez Trace Library, Tupelo, MS, p. 53.

2. Carpenter, Viola H., “Some Lawrence County Iron Mongers And Their Mines.” Yesterday

and Today In Lawrence County, [Tennessee], Volume VII, Issue 3.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Smith, Samuel D., et al, A Cultural Resource Survey Of Tennessee’s Western

Highland Rim Iron Industry, 1790’s – 1930’s, Tennessee Department of Conservation,

Division of Archaeology, Research Series #8, 1988, pp. 88-89.

6. Carpenter

7. Ibid.

8. Smith, page 88.

9. Carter, Maymaud & Joan C. Hudgins, 1850 Census of Lawrence County, Tennessee,

page 105.

10. Warren, Polly C., Lawrence County, Tennessee 1840, 1860 Census, Private Acts and

Miscellaneous Newspaper Extracts, P-Vine Press, n.d., p. 86.

11. Map, Army of the Cumberland, US Army, Corps of Engineers, 1863.

12. Smith, p. 89.

13. Whitney, Henry D., comp., ed., The Land Laws of Tennessee, Chattnooga, J. M.

Deardorff & Sons, 1891, p.954.

14. Smith, p. 89

15. Ibid.

16. Purdue, A. H., The Iron Industry Of Lawrence and Wayne Counties, Tennessee”, The

Resources Of Tennessee, Volume 2, Number 10, October 1912, pp. 375-376.

17. Smith, p. 89.

18. Purdue, p. 375.

19.Miser,Hugh D., Mineral Resources Of The Waynesboro Quadrangle, Tennessee,

State Geological Survey, Bulletin #26, 1921,p. 46.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Scott, Alf & June, Census Records of Wayne County, Tennessee, Volume

5:1900, pp. 123-148.

23. Buffalo Iron Company to Bon Air Coal & Iron Company, Deed, 5 August 1902, Wayne

County, Tennessee Deed Record, Book Y, pp. 124-215.

24. Miser, p. 46.

25. Wrigley, Wm. F., Jr. private correspondence, Wm. F. Wrigley, Jr. Company Archives,

Chicago, Illinois.

26. Wrigley, Wm. F. Jr. to J. H. Patrick, personal correspondence, 5 August 1918.

27. Lawrenceburg, Tennessee “Democrat”, 17 June 1917.

28. Smith, p. 88.

SOURCES:

Anonymus, “From The Collinwood Pilot,” Democrat, 17 June 1917,

Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.

Carpenter, Viola H., “Some Lawrence County Iron Mongers And Their Mines,” Yesterday

and Today in Lawrence County [Tennessee{, Volume Vii, Issue 3.

Carter, Marymaud K., & Joan C. Hudgins, 1850 Census of Lawrence County,

Tennessee, privately printed, Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, n.d.

Miser, Hugh D., Mineral Resources Of The Waynesboro Quadrangle, Tennessee, State

of Tennessee, State Geological Survey, Bulletin 26, Williams, Nashville, 1921.

Phelps, Dawson, “Stands and Travel Accommodations On The Natchez Trace”,

unpublished manuscript, Natchez Trace Parkway Library, Tupelo, MS, n.d.

Purdue, A. H. “The Iron Industry of Lawrence and Wayne Counties, Tennessee,” The

Resources of Tennessee, Volume 2, Number 10, October 1912. Tennessee Geological

Survey, Nashville, Tennessee.

Scott, Alf & June, Wayne County, Tennessee Census Records, Volume 5: 1900,

The Byler Press, Collinwood, Tennessee 1988.

Smith, Samuel D., Charles P. Stripling, and James M. Brannon, A Cultural Resource

Survey of Tennessee’s Western Highland Rim Iron Industry 1790’s – 1930’s,

Tennessee Department of Conservation, Division of Archaeology, Research Series #8, 1988.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Map – Army of the Cumberland, 1863, US Archives,

Washington, DC, unpublished.

Warren, Polly C., Lawrence County, Tennessee 1840 Census, 1860 Census, Private Acts,

Miscellaneous Newspaper Abstracts, P-Vine Press, Columbia, TN, n.d.

Wayne County, Tennessee Deed Records, Book Y, Wayne County Courthouse,

Waynesboro, Tennessee.

Whitney, Henry D., comp., ed. The Land Laws Of Tennessee, Chattanooga, J. M.

Deardorff & Sons, 1891.

Wrigley, William F., Jr., Private Correspondence, William F. Wrigley, Jr. Company

Archives, Chicago, Illinois.