Grand Junction Deaths

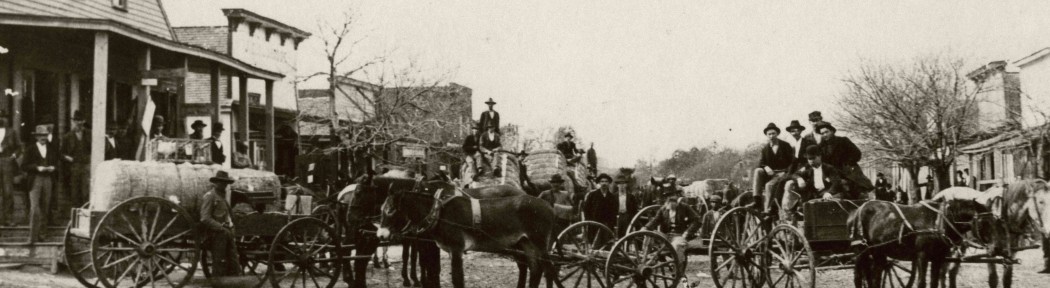

Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878

56 White Victims as Published in the Bolivar Bulletin

Miss M.B. Moore – A teacher from Memphis – age 30 years

Mrs. E.W. Belew – A refugee from Granada, Mississippi – age 25 years

Mrs. Hewitt – A refugee from Memphis – age 25 years

George Lloyd – A clerk, age 60 years

W.J. Owens – A farmer – age 35 years

Mrs. W.J. Owens – A house wife – age 30 years

Miss Julia Culligan – A child of 14 years

Robert Clampitt – A carpenter, age 35 years

Mrs. Mollie Clampitt – Housewife, age 30 years

Harris Clampitt – Child of Robert and Mollie Clampitt – age 9 years

Chalmers Clampitt – Child of Robert and Mollie Clampitt – age 11 years

W.W. Pledge, Jr. – Express Agent, age 22 years

C.V. Prewitt – A farmer, age 30 years

Ernest Prewitt – Son of C.V. and A. Prewitt, age 2 years

Mrs. Eugenia Stinson – Wife of A.F. Stinson, age 24 years

Cyrus F. Stinson – Son of A.F. Stinson, student, age 8 years

Samuel Stinson – Son of A.F. Stinson, age 7 years

Charles Stinson – Son of A.F. Stinson, age 5 years

Frank Hawkins- Ran a boarding house, age 50 years

Frank Lavender – Marble cutter, age 28 years

Harry Lavender – Son of Frank Lavender, age 5 months

N.P. Hazzard – A clerk, age 16 years

Jasper Lavender – A marble cutter, age 23 years

Dr. N.H. Prewitt – A physician, age 45 years

Mrs. Nannie C. Prewitt – A housewife, age 45 years

R.P. Milam – Mail agent, age 23 years

Mrs. Bettie Hayes – A milliner, age 39 years

Mrs. Melora Smith – A housewife, age 45 years

Beauregard Smith – A student, age 16 years

Mary Tucker – A daughter of Smith Tucker, age 6 years

Susie Tucker – A daughter of Smith Tucker, age 3 years

J.H. Prewitt – A farmer, age 40 years

Mrs. Mollie Prewitt – Wife of J.H. Prewitt, age 35

T.E. Prewitt – Son of J.H. & Mollie P. Prewitt, student, age 18 years

Mrs. Susan Pledge Jennings – Of Madison, Alabama, 24 years

Booker Swann – Telegraph operator, age 22 years

Thomas E. Jones – Express Agent, age 25 years

Mr. Handy – A telegraph operator

James Netherland, Jr. – Hotel clerk, age 19

Parvin Netherland – Son of James Netherland, age 3

A Stranger – Occupation unknown

A Stranger – Occupation unknown

Dennis Flannery – Saloon keeper, 30 years

Mary Flannery – Daughter of Dennis Flannery, 3 years old

Mrs. Dennis Flannery – Housewife, 25 years old

W.J. Woods – Saloon keeper, age 45 years old

Annie Woods – Daughter of W.J. Woods, age 15 years

Mollie Woods – Daughter of W.J. Woods, age 18 years

Willie Woods – Son of W.J. Woods, age 7 years

Kittie Woods – Daughter of W.J. Woods, age 5 years

Virginia S. Bowers Patterson – Wife of M.A. Patterson, age 59 years

Smith Patterson – A teacher, age 37 years

William W. Bass – A farmer, died October 16, 1878, age 30 years

Mrs. Mary Prewitt – Wife of P.H. Prewitt, age 70 years

Mary L. Bledsoe – Wife of James Bledsoe, age 17 years

Mae Prewitt – Daughter of S.L. Prewitt, age 3 years.

The 56 Yellow Fever victims of Grand Junction listed above are all white. There were 20 Negro deaths. Their names were not given for publication. Of the whites who had the fever, 15 survived and are now considered well. Ten are considered convalescent, and three are still sick on October 31, 1878.

Dr. N.H. Prewitt sent this letter to the Bolivar Bulletin before he succumbed to the Yellow Fever epidemic in October of 1878:

“I am thoroughly demoralized by the deaths of so many friends and relatives. My brother, Joe, was convalesing, got up and arranged personal effects and moved over to Brother Dr. Tom Prewitt’s, relapsed, and I saw him put beneath the sod day before yesterday. Sister Nannie O. Prewitt, the widow of the late Jack Prewitt and mother of R.P. Milam, one of our first cases, died the night before. She contracted the fever while waiting on that dear son. I took her to my house. She was the oldest sister of my wife and a member of the Presbyterian Church. I have three convalescents in my house. Arthur is up and running the whole post office Department at this place. Sister Alice Prewitt, wife of dear C.V. Prewitt, who is dead, also has the fever along with little Susie and her dear mother. What terrible times! Excuse so much personal news. Since my last letter, we have lost our noble Tom Jones of the Express Office. The Lavender brothers and Tom Jones all died within 15 minutes of each other. The Lavenders were accountable in their work of burying the dead and their places cannot be easily filled. We are dependent on Isaac Toler, John Stone, and Tony Jordan (all colored) to bury the dead. We cannot too highly praise these colored men. Mr. Clampitt died yesterday. The death number to date is about fifty. There are several new cases under treatment with three or four dangerous. Dr. Tom Prewitt is now relapsed and in critical condition.”

Bolivar Bulletin Article, October 10, 1878:

Honor to Whom Honor is Due – While others have nobly done their duty, Dr. Nathan H. Prewitt, of the Junction, is singularly conspicuous among the heroic physicians of the stricken South in standing so true to his professional obligations to the public. He and his brother, Dr. Tom Prewitt, are entitled to the largest measure of praise for their devotion and self sacrifice which they have manifested all through the terrible fever scourge at the Junction. The following letter from the distinguished Dr. W.H. Beatty speaks for itself. “To Mr. G.W. Armistead, Editor of the Bolivar Bulletin: At the call of your state, I was sent to Grand Junction and found things in a terrible condition. Most of the best people had (I think wisely) fled. One of the local doctors was very sick and the other, Dr. Nathan Prewitt, would have been in bed but for his indomitable energy and determination. He really had the fever when I arrived, but he took me to see every sick person in town at a time and under circumstances when any other man I ever saw would have been in fear, and during my entire stay of three weeks, he aided me in every possible way in my efforts to relieve his sadly afflicted neighbors and friends. But for him, I could have done nothing and would have left in despair. Your readers already know what terrible ravages the disease made at Grand Junction. I want them to know that but for Dr. Nathan Prewitt, it would have been vastly worse, and therefore, ask that you publish this, which will take Dr. Prewitt by surprise more than anyone else. Signed, W.H. Beatty, M.D.

Dr. Nathan H. Prewitt died October 11, 1878 of Yellow Fever and lies buried in the Grand Junction Cemetery. He was born August 6, 1829. He was the son of James and Elizabeth Hill Prewitt (both buried at Mt. Comfort Cemetery.)

From the Jackson Tribune and Sun:

Shocking Inhumanity Near Milan

Young Howlett, aged 10 years old, a grandson of Mr. Pledge, the hotel man of Grand Junction, passed up to Milan a few days ago where his grandfather was staying. Being from an infected area or town, although having stayed in it only a few hours, he could not remain in Milan. His grandfather rented an isolated cabin a mile or more from town and hired a Negro woman to take the boy and stay with him until the days of his quarantine were completed. The first night in the cabin was a terrible one in his experience. A few persons whom fear and cowardice had made brutes of themselves went to the cabin, stoned it, shot into it, and ran the poor little fellow out into the night and darkness, and fired shot after shot at him as he fled in wild terror. The little fellow remained all night in the woods wandering and hiding in pitiless cold. Next morning he crept into Milan and his grandfather took him to a place of safety. Now we respect quarantine, we respect the fears of the people in these terrible times, but such treatment as this little boy received is simply inhumane and brands the authors as brutes and cowards. We know the respectable people of Milan condemn the acts denounced by us fully as much as we do and we further know that the Milan authorities and quarantine officers are guiltless of any connection with the perpetrators, but they should hunt down the guilty and see that they are punished.

A survey of the Zion Temple II Cemetery has been added. The cemetery is located southwest of Grand Junction off of Smith Road.

New website containing over 1,500 documents that operated in Bolivar and the surrounding area.

During the Civil War, the Provost Marshal was the Union Army officer charged with maintaining order among both soldiers and civilians. Records for Hardeman county have been added to a TLSA database: Union Provost Marshall Database

There are at least twelve (12) African Americans buried in Polk Cemetery in Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee.1 Various documentation contains the names of these individuals: three blacks have headstones; seven are mentioned in the Diary of John Houston Bills;2, 3 one is documented on March 2, 1902 in a Memphis, Tennessee Commercial Appeal newspaper article about Ezekiel Polk;4 and the twelfth is recorded in burial records of St. James Episcopal Church in Bolivar.5

* Three graves of African-Americans with headstones:

1. John McNeal, April 16, 1907, age 57;

2. Lila, wife of John, September 1909; [John and Lila had no children. Their estate was left to a niece, Lily Moore.]

3. In Memory of Rueben B., faithful servant [of John H. Bills] and honest man, 1846.

* Seven African-American burials mentioned in John H. Bills’ diary:2, 3

1. Charlotte, died July 28, 1853. “Thursday, July 28, 1853 … Our house servant, Charlotte, died this morning at 3 o’clock. She had been sick for 24 days of typhoid fever, during all of which time Dr. Neely attended her without affecting the slightest good in her case. We bury her in the family [Polk] Cemetery at 5 p.m.”

2. Victoria’s infant Emma, February 24, 1863 – Tuesday August 18, 1863. Victoria was a house servant who was a “general attendant.” It appears she attended Clara Bills (John H. Bills’ daughter). “Wednesday, September 18, 1861, Clara Bills & svt Victoria off for a visit to her friends at Huntsville.”

It appears Victoria was acquired by John H. Bills between 1845 and 1856. He referred to her several times in his diary. She “jumped the broom” with Willis, a servant of Dr. Wood, on Monday, December 29, 1862. She had an infant on February 24, 1863, who died on August 18, 1863. “Early this morning Victoria’s infant Emma died, disease convulsions from whooping cough … I bury Vic’s infant in the Polk Cemetery.”

3.- 7. Sam Bills, his wife Lucretia (Creasy), Creasy’s daughter Martha

Martha’s husband Willis, and Sam’s “only son.”

Sam Bills, circa 1797 – September 10, 1869. Sam was buried in Polk

Cemetery one day after his death (September 11) “beside his only son.”

John H. Bills had purchased Sam on February 19, 1839 from John Lea for $650.00. (John Lea was the person who sold The Pillars to John H. Bills. Hence Sam changed owners but stayed on the same plantation.) Sam was about 42 at the time. Sam held a special place with John H. Bills. Bills had Sam baptized “by sprinkling” on Saturday,

June 19, 1858. Bills’ diary contains no other mention of baptism of any other slaves.

Sam was a “good old servant” who had been with Bills “more than 30 years.” Bills wrote that Sam died of “old age – he was a faithful honest man, refused to leave me when free & was true to my interest during the War of the Rebellion – peace to his ashes.”

Lucretia (Creasy) Bills, wife of Sam, circa 1805 – December 24, 1870. John H. Bills purchased Creasy and her two children (Bob and Martha) on July 17, 1833 from Humphrey Keeble. Creasy was about 28, Bob was 2, and Martha was 2.

Creasy served as a milkmaid for Bills. She died just over one year after the death of her husband Sam. “Old Creasy who has been sick for 3 weeks expires at 9 ½ a.m.” Creasy was buried the next day at 2 p.m.

Martha Bills Mayhugh, daughter of Lucretia (Creasy), circa 1831 – September 17/18, 1870. Martha “jumped the broom” with Willis, another slave of John H. Bills. After Willis’ death, she married WilliamMayhugh on May 26, 1866.

On September 18, 1870, John H. Bills wrote, “Arrive at home at 5 ½ o’clock [a.m.] & find my ex servant Martha dead. She has been sick along time, leaves 7 or 8 helpless children.”6

Willis, husband of Martha, circa 1817 – September 16, 1862. John H. Bills purchased Willis on November 28, 1849 from Lucy Wynne. Willis was about 32 at the time. One day after his death, Willis was buried in Polk Cemetery.

Sam’s only son – name and dates unknown; died before his father, who died on September 10, 1869.

* Jim, slave of Ezekiel Polk, circa 1776 – between 1860 and 1870.4

According to a Commercial Appeal newspaper article about Ezekiel Polk dated March 2, 1902, “… In 1849 Edwin Polk gave the land for Polk Cemetery in southwest Bolivar, ‘to be forever a family burying ground.’ To this place Ezekiel Polk’s remains were removed in the early 50s, and a second monument erected. Close by was put to rest ‘Uncle Jim,’ his faithful servant, who followed his master’s fortunes from Pennsylvania to Middle Tennessee; thence to West Tennessee. A daughter of this same Uncle Jim is at present living in the Polk place in her ninety-sixth year.” [Some of the dates in this article are not accurate. According to John H. Bills’ diary:

Thursday, November 20, 1845 – A fine day. We spend it removing the remains of our friends to the Polk Cemetery. We succeed in removing all the tombstones & the bones of Colonel Ezekiel Polk ….

It also appears that Ezekiel Polk brought Jim to Tennessee from North Carolina, not Pennsylvania.] Note: After Ezekiel Polk’s death, Jim became a slave of Ezekiel’s son Edwin Polk, and, after Edwin’s death in 1854, was inherited by Edwin’s wife, Octavia Jones Polk.

The daughter of Jim, who was referenced in the Commercial Appeal article, appears to have been a freedwoman named Lively Polk.

* Rena, slave of Major [E. P.] McNeal, died March 6, 1865.5

St. James Episcopal Church documented the funeral of: “… Rena an old servant of Maj. McNeal’s at Polk Cemetery – services at the grave.”

It is reasonable to assume there are other African Americans buried in Polk Cemetery. The above twelve slaves/freedpersons are ones about whom we have documentation.

SOURCES:

1 Polk Cemetery is located on S. Union Street in Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee. Some of Hardeman County’s most prominent citizens are buried there, including Colonel Ezekiel Polk, grandfather of President James K. Polk.

The twelve African Americans mentioned above are buried in the Southwest corner lot.

2 John Houston Bills Papers, Series 2, Diary, 1843-1871. Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Microfilm Accession Number J8.

3 “Diary of John Houston Bills,” Bills Family Papers, 1826-1877. Manuscript Unit, Tennessee State Library & Archives, Nashville, Microfilm Accession Number 123, 1972. (This diary is an extracted, typed transcription by Virginia M. Bowman, third great granddaughter of John Houston Bills. It contains some errors.)

4 “Ezekiel Polk, His Life and Character,” Commercial Appeal, Memphis, Tennessee, March 2, 1902.

5 “Funerals,” Church Records. St. James Episcopal Church, 223 Lafayette Street, Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee, page 171.

6 Names of nine children of Martha Bills Mayhugh are noted in Plantations of John H. Bills, his Slaves and Their Descendants, 1820 – 1920, by Katie Brown Bennett. A copy of this book is available in the Hardeman County Regional Library, Bolivar.

COMPILED AND SUBMITTED BY: Katie Brown Bennett