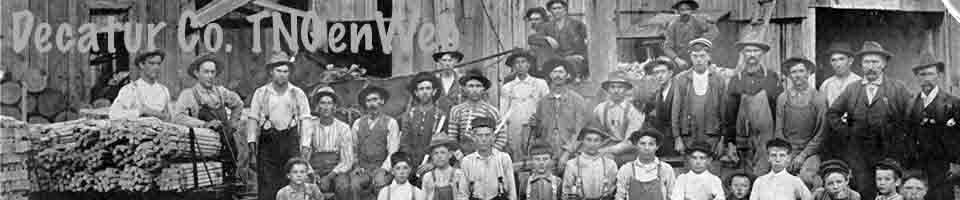

W. V. BARRY ON DECATUR COUNTY NEGROES

compiled by Brenda Kirk Fiddler

Wall Hotel in Perryville

Information is needed on the old Wall Hotel in Perryville. We have an unconfirmed picture of the hotel as well as some newspaper articles about it but we need to learn more about it. Please contact me if you can help with information about the Wall Hotel, formerly located in Perryville.

This Is My Column (excerpt)

March 8, 1940, Lexington Progress

Last Tuesday a card came from my brother-in-law, Bill Dennison, at Perryville, brought news of the death of my old colored friend Ike McDonald, which occurred last Saturday, and Ike had reached the age of 81. The death of Ike left but two of the old citizens of old Perryville that I loved so well, from the days when Mrs. John Wall and her daughter, Mollie, ran the old Perryville Hotel--but in those days Brother Bill and Tom Stout were boys in Decaturville. Ike McDonald came from a respectable Negro family; his father, old Jim, owning good mules and wagons with which he did all the hauling of goods from a Tennessee River landing to the George Kittrell store at Farmer's Valley. I wish I could have visited Ike before he went to that place where there is no racial distinction.

My Column (excerpt)

December 13, 1940, Lexington Progress

Way back when I lived in Decaturville, it must have been in 1882, when the Tennessee River got on one of its greatest rampages, a crowd of us were sitting in the store of G.W. Smith and Son, when Perry Houston and his son, Bill, came in and were first to have crossed the iron bridge at Buckner's Mill. In the crowd the general topic was high water, and when the time came an elderly man, known as "Uncle Boyd," told of his experience, riding a mule in the high waters in the state of "Elynoy," as he had always pronounced Illinois. Uncle Boyd said that when he got into water too deep for the mule to ford or wade without swimming, the animal rose on his hind feet and he slipped over its tail. At this juncture, Uncle David Funderburk, who never saw a joke in his life and did not like Uncle Boyd anyhow, sat in his chair with his feet firmly planted, his walking cane in his right hand with his head leaning against the counter, kicked forward with both feet, bumped his head against the counter and said, "Gad sir,you took that mule on your back and swam out," to which Uncle Boyd replied, "I did nothing of the kind," and Uncle David continued, "I am satisfied if you will refresh your memory, that you took that mule on your back and swam out." Nothing daunted, Uncle Boyd finished his story, but I have forgotten how Uncle Boyd and that mule got out of that high water.

Continuing about Uncle David in the same store one day, Tom Ramsey, son of the local circuit rider, remarked that if a certain bill passed the legislature, forbidding the sale of snuff within four miles of a female institution of learning, the women would get to chewing tobacco, whereupon Uncle David Funderburk remarked, "Get at it--By gad son, they've been at it ever since I can remember," and Uncle David was an old man with a nervous affliction which gave him a very tottery walk.

It seems to me that I have told the story as related to me by Add Funderburk, an aged colored man who lives here, how his old master, Uncle David, was twice hanged in the effort to force him to tell the hiding place of his money which Uncle David would not do, and would not have done, but before he was strung up the third time, Mrs. Funderburk told where the money, a few hundred dollars, could be found. By the way, Uncle Add Funderburk is the only Negro man I know that was born a slave.

My Column

July 7, 1944, Lexington Progress

I have been switched away from what I began to write about colored people so often, that I now hardly know where I left off, but I believe I resume with Decatur County, where Harve White, a well-liked young Negro man, was deliberately shot down by a white hoodlum, "Snort" Simmons, who had already killed another Negro named Scott, all of which happened between the old Frayer Hotel and the house immediately across the street. Harve was shot in the stomach, said to be identically in the same spot of the shot which killed President Garfield. Harve was carried to his cabin, laid on a pallet on the floor, was visited occasionally by a doctor, and got well. President Garfield had a swarm of doctors every hour or less--and he died.

Harve White was a good Negro, lived many years but had an unfortunate ending. One winter day he drank too much liquor, went to his home, and that night froze to death--at least he was found dead next morning. Time after time going back to Decaturville after I moved back to Lexington, I always had to shake hands with Harve, and I didn't object.

The outstanding Negro citizen of Decaturville before I went there in 1881, was Uncle Aaron Yarbro, who at one time was "well to do" financially, but lost out by the trickery of a white man, I was told. Uncle Aaron died no better off than the average colored man of his age.

Another notable Negro in Decaturville was Charles Shelton, generally known as Coon," who pretended to be a barber, but never did learn to give a decent shave or hair cut, and really he was the local bootlegger, who bought his liquor at Perryville, made it half water at a spring half way to Decaturville with the fact that the brand was "Rot Gut" when bought at Perryville. Hundreds of times old "Coon" was called at night for various purposes, and never a single time was he found to be asleep.

For a time in Decaturville, it had been the custom when a death occurred, for the business men to close their store and dig the grave, but that was finally quit, and Charlie Shelton would dig the grave for $100. So when I moved to Lexington and had to pay $5.00 for digging a grave, I thought it was little short of highway robbery.

One more mention and I am done--the MacDonald family, old Jim and his sons.

Jim lived on a ridge on one of the roads to Perryville, and one end of his house was a room where a table was always set to give any white person a meal. Old Jim had a wagon and two or more mules, and hauled all the goods from Tennessee River landing to Farmers' Valley, and the store of George Kittrell.

Jim's sons, as I remember them, were Lewis, who lived to be a very old man and died not long ago in Lexington; Frank, who lived and died at Perryville--and thereby hangs a tale; Ike, who went blind and died a few years ago, and still another who ran the ferry boat at Perryville, and whose name I do not remember.

The first winter that the Tennessee Midland Railroad ran to Perryville from Memphis, Frank McDonald was said to have the contract to furnish the fuel to every business. All went well for a while. Frank would take his sack, go to the cars of coal standing on the track, fill the sack with all he could carry, and deliver it to the store, saloons or whatever it might be.

Unknown to Frank, a new night watchman was appointed and when he made his first trip and began to fill his sack, he was seen by the watchman who cracked him down with a pistol. Frank made a running record for all of Perryville, and all of the coal burners came pretty near freezing until new arrangements could be made.

Frank McDonald quit drinking liquor on his own accord and for the last few years of his life, was a pretty good man.

Once more I have written too much and will have to leave my story untold until a future date.