Home Guards Lead to Post-Civil War Feuds in Fentress County, TN

by Dave Tabler (posted 2013)

“No section of the great Civil War suffered so enduringly as that which was the boundary line between the sections, and no part of the boundary suffered more from devastations of war in the passing to and fro of armed forces and from the raids of marauding bands, than did Fentress County, TN.

“Before the war the county had been sharply divided politically, and with few exceptions that alignment held. Those who were Union sympathizers went north into Kentucky and joined the Federal forces, and those on the side of the South went for enlistment in the armies of the Confederacy. The men who remained at home were compelled by public sentiment to take sides, and the bitterest of feeling was engendered.

Samuel “Champ” Ferguson

“The raids of passing soldiers was the excuse for the organization, by both sides, of bands who claimed they were “Home Guards”—the Federals under Tinker Beaty, and the Confederates under Champ Ferguson. These bands, each striving for mastery, developed into guerrillas of the worst type the war produced, and anarchy prevailed.

“Like so much of the state, the Tennessee area known as Valley of the Three Forks o’ the Wolf paid its tribute of blood and money. At the outbreak of the war, local son Uriah York went north into Kentucky and joined the Federal forces. Taken ill, he had returned to the home of his wife’s father at Jamestown, TN, and while in bed learned of the approach of a band of Confederates. He arose and fled for safety to a refuge shack his father-in-law had built in the forest of Rock Castle. His flight was made in a storm that was half rain and half sleet, and from the exposure he died in the lonely hut three days afterward.

“Meanwhile, back in Three Forks, Elijah Pile’s four sons were divided in their allegiance—two upon each side. Two of them paid the supreme price, murdered by opposing Home Guard bands as they rode along public highways.

Elijah Pile’s father built the family cabin in Fentress County beside a spring, now called York Spring.

“Conrod Pile, like his elderly father Elijah, was a non-combatant, but sympathized with the North. In the autumn of 1863, for some cause unknown to his relatives, he was taken prisoner by Confederate troops, members of Champ Ferguson’s band. As they rode along the road with him, some shots were fired. They left him there.

“In June of the following year, Jeff Pile, a brother of Conrod, was riding along the road beyond the mill that creaks in the waters of Wolf River. He had taken no active part in the war, but was a Southern sympathizer. Some of Tinker Beaty’s men galloped into sight, fired, and galloped on.

The murder of Jeff Pile threw a red shadow across the years that were to come after the war was ended.

“One of Tinker Beaty’s men was Pres Huff, who lived in the Valley of the Three Forks o’ the Wolf. It was generally believed that he was the leader of the band who had ridden out of the woods and killed Jeff Pile, as he traveled unarmed along the Byrdstown Road.

“Huff’s father had been shot. The deed was done by a band of Confederates who had taken the elder Huff prisoner, and neither Jeff Pile nor his brothers were connected with it, except in the quickly prejudiced mind of the victim’s son.

“When General Burnside was moving his Federal forces southward there came to the town of Pall Mall, TN, a young man by the name of William Brooks. He had joined the Union Army at his home in Michigan. He was a daring horseman, handsome, fair and his hair was red – a rich copperesque red.

“The army moved on, but young Brooks remained in the valley. He claimed that as a private soldier he had done more than his share in the conquest of the South—and that the conquest that should ever go to his credit was the conquest of one Nancy Pile.

“When they were married, his father-in-law, Elijah Pile, gave him a farm, and he tilled it, and he smiled his way into the favor of the community.

“He lived in the valley about two years, and a baby had been born to them. The feeling between the children of Elijah Pile and Pres Huff was silent but tense; over it there fell constantly the shadow of the murder of Jeff Pile.

“Meeting down at the old mill one day, Pres Huff and Willie Brooks engaged in an excited argument. Between the dark-browed, sullen mountaineer and the slender, gay young man a contest seemed uneven, and was prevented. Huff told Brooks that the next time they met he would kill him.

“They met next day, on the mountainside, on the road that leads by the Brooks home, on across the spring branch, up beside the York home and then up the mountain. Huff’s riderless horse galloped on and stopped in front of a mountain cabin; his body lay dead in the road.

“There was a hurried consultation at the home of Elijah Pile. Huff’s friends, it was realized, would not be long in coming. Young Brooks went out of the house, down by the spring, and up the mountain back of it. He was never seen in the valley again.

“Huff’s friends waited.

“Weeks afterward, Nancy Brooks, carrying her baby, went to visit a friend. She evaded the watchfulness of her husband’s enemies, succeeded in crossing the Kentucky line and disappeared in the mountains to the north of it.

“The friends of Pres Huff knew she would write home. Months elapsed, but finally a letter came, and was intercepted. She and her husband were at a logging camp in the northern woods of Michigan.

“Secretly, extradition papers for Brooks were secured, and Huff’s former partner in a mercantile business, fully equipped with warrant, appeared with a sheriff before the door of the cabin in the Michigan woods. Brooks was brought back to Jamestown, and put into the log-ribbed jail that John M. Clemens, Mark Twain’s father, had built.

“But there was no trial by law. The next night, through the moonlight and the pines, a little body of men rode. Up the valley, across the plateau, they went, and Jamestown was sleeping.

Grave of William Brooks, Wolf River Cemetery, Pall Mall, TN

“Taking Brooks from the jail, they carried him three miles down the road toward Pall Mall. Here they bound a rope around his feet, unbridled a horse and tied the other end of the rope to the horse’s tail. They taunted Brooks. But they could not make him break his silence, until he asked to be allowed to see his wife and baby. Rough men laughed, and there was the report of a gun. The horse, frightened, galloped down the road, and bullets were fired into the squirming body as it was dragged over the rocks.

“The war had steeled men for the coming of death and crime, but at the manner of the death of Willie Brooks a shudder passed over the mountainsides. To Nancy Brooks was born a son a short time afterward, and he was named after his father.

“A silent, broken-hearted woman, Nancy Brooks took up again her life at her father’s home. To the little girl she had carried on her flight to Michigan, and to the boy whose hair had the copper-red of the father, she devoted herself.

“The girl had been named Mary, and she inherited the piquancy and wit that had made her mother the belle of the valley, and as she grew to womanhood the mountaineers saw again the Nancy Brooks they had loved before war had come with its cold blighting fingers of death.

“At the age of fifteen Mary Brooks met William York, the son of Uriah York, and they were married. A home was built for them, beyond the branch, beside the spring. And Alvin York was their third son.”

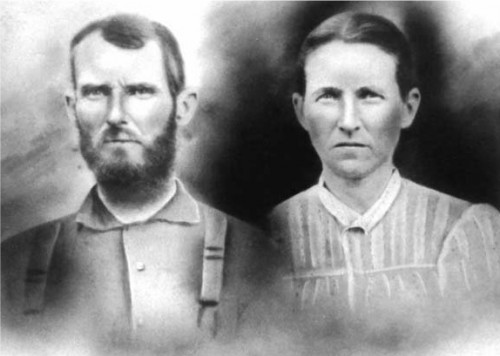

Alvin C. York’s mother and father, William and Mary (Brooks) York

Source: https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2013/01/home-guards-led-to-post-civil-war-feuds-in-fentress-county-tn.html (available via the Internet Archive)

Note on original post: Excerpt from Sergeant York and His People, by Sam K. Cowan

(New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1922). Click here to read the full text transcription.