cumberland lore

Stockade Annie Was Soldiers' Friend

By Charles Waters

Not often does a person live to become a legend in his or her own time, but Anna Mabry Barr, better known in Clarksville as "Stockade Annie," had achieved that distinction.

Mrs. Barr was a familiar figure in C1arksville and Fort Campbell as she administered to prisoners and soldiers in the jails, hospitals and stockade. She was granted a free run of the stockade and was the only person allowed to talk with prisoners without custodial personnel being present.

Her career as "Stockade Annie" began at the age of 66, when she visited a badly burned soldier from the stockade who was at the post hospital. She held his hand all night and spoke soothing words to him as he awaited treatment.

The next morning the burned soldier asked, "Whereís that old woman who held my hand and talked to me?" When a nurse called Mrs. Barr in, a legend began.

And her reputation continued to grow. At first her access to soldiers was limited, so she went to the commanding general of the post and asked for a pass to the stockade.

"I couldnít have caused more sensation if I had asked for a pass to heaven. Thereís no such thing, I was told," she reported to a number of writers who had interviewed her.

But she did not take "no" for an answer. Every Sunday for a year she went to the headquarters and asked for a pass. "I always take the direct approach," she said.

Persistence paid off, for how long could a general refuse an aristocratic old lady? She was issued the pass, the first of

dozens or more that she would be given in her lifetime.

Trying to discourage her once, an irate young officer asked, "Just who do you think you are?"

"Iím a capital ĎSí ó sovereign citizen and full-fledged taxpayer. If this isnít my camp and my army, whose is it?" she replied.

Her reply was consistent with her character and reputation. Family and friends have recalled that even as a young woman, Anna Mabry usually got her way, and this characteristic over the years helped her earn a reputation as being "eccentric." Some said "crazy", but she was an extremely intelligent person who had published: "My Old Field" and "Vivid Night." She also wrote poetry.

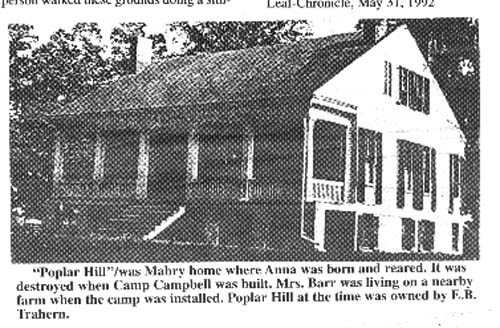

Fort Campbell was really home for Anna Mabry Barr because she was born there in 1876, one of 12 children, the sons and daughters of Thomas Laid Hettie and Bettie Dabney Mabry. The family home, known as "Poplar Hill" (or sometimes jokingly as "Populous Hill") had been in the family since 1835 when her great-grandfather David McManus came to Montgomery County and bought 1,356 acres in District 4. One of his daughters, Malinda, married John E. Mabry and they inherited a part of McManus estate. The older members of the family rest in the graveyard just off Mabry Road, up the hill from Boiling Springs Road on the Fort Campbell reservation.

Anna was tutored at home until she was 12, when she attended a "real" school.

As a young woman, Anna was a popular but headstrong young Southern belle among the affluent group associated with the Mabrys. She met and married Dr. John Christy Barr, a prominent Presbyterian minister. They moved to New Orleans where he served churches for 30 years. They returned to Montgomery County in 1939 and set up residence on a large farm, once a part of the Mabry property. "That's why I am such a sophisticated old lady," she said once to a reporter. "My husband never knew what I was going to dó."

And neither did friends and neighbors in 1941 when the survey began on the site of Fort Campbell.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act had been passed, but she would have no part in government programs. One day she appeared at the local agricultural office (at that time located in the basement of the Post Office) and demanded to know why, without her consent, the government had taken an aerial photograph of her farm. She was not satisfied with the answer given her.

But the real fireworks began in 1941 when it was announced that the government would take her farm as a part of Camp Campbell. She flatly refused to move and went so far as to chase surveyors off with a shotgun. Neighbors, watching the scene, predicted that Mrs. Barr would win.

But then her husband died and Mrs. Barr changed her mind. She decided to devote the remainder of her life to serving the young men who would be training at Camp Campbell. And so began her visits

to the hospital, where she met soldiers who were sick or in trouble. Then she moved to the stockade to help "her boys."

Following Dr. Barrís death, Mrs. Barr built a log cabin on the highway in front of a bluff about a half mile south of Gate 1. She later moved to Hopkinsville where she said she did not "live."

"I live on wheels and just sleep in Hopkinsville," she explained.

"I never had any children, but I have the biggest and best family in the world. Some are robbers, some are murderers, some are thieves, and some are victims of unfortunate circumstances. But they are my children," she said.

When Anna needed money for her children, she knew how to get it. She went straight to the president of a bank once and told him she needed $200 to buy Bibles for "her boys." The president asked what collateral she could offer to secure the loan. When she told him that

she had only the clothes on her back, he hesitated and began to explain regulations under which bankers operated. She stopped him in mid-sentence and said, "Young man, God will see that this loan is repaid."

With such eminent security, the banker felt he had no recourse but to grant the loan. He did, and she repaid it on time.

Anna Barr did just not talk. She acted and protected her children. She discovered once that seven men from the same unit had been put in the stockade. She talked with them and decided that they

had been wrongly imprisoned. She went straight to the commanding general and an investigation proved her correct. The company officer received a reprimand.

Commanding generals did not intimidate "Stockade Annie."

Once when a new commander was assigned to Fort Campbell he heard that some old lady had a pass to the stockade. He ordered it rescinded. The next day when she learned of his action she demanded to see him. She was told that he general was busy, but Mrs. Barr burst into his office unannounced. The general was holding a meeting, but she was not to be denied.

One who was present reported "Iíve never heard a private chewed out like that general was chewed. She really ripped him up." Her pass was renewed.

Mrs. Barrís reputation and influence grew to the point that her wishes carried teh weight of commands. She noticed that the fort was flying its honor flag on Lincoln's birthday. She demanded it be flown on Gen. Robert E. Lee's also.

And it was.

Her reputation grew and she won friends in high placed, including officials at the Pentagon. When she was denied a request (perhaps a demand was more accurate) by a Fort Campbell commander, she would call someone at the Pentagon and soon a message came down from Washington to do whatever she wanted.

Stockade Annie even visited the Pentagon because she said she bad a message from God that she was to deliver in person. She traveled by bus (she had a free pass from Greyhound to anywhere she wanted). She sat all day on the steps of the Pentagon and finally gained the interview she was seeking.

According to Bill Mabry, Mrs. Barrís nephew, only one person remained inaccessible to her. That was President Nixon.

She was greatly upset by the Vietnam War because her boys were being killed and wounded. In 1969, she took the bus to Washington to let Nixon know just bad she felt. She waited all day, but was told by H.R. Haldeman that the president could not see her: Haldeman promised her that he would deliver her message, but that was not good enough. She took the bus home and, died a few months later. If she had been given enough time, those who knew her felt that she would have worn Nixon down.

Mrs. Barr dealt with her boys just as she did with everyone else. She learned army slang so she could communicate more effectively with them. To those in the "hot box," or those who had been put "in cold storage" she spoke firmly but lovingly. "This is where you belong; learn something from it and become a better man," she advised prisoners. "If you are in the hot box, call on Gód...pray hard and heíll do it, too!"

And her boys listened. "Iíve seen times when within an hour, a man who was belligerent and disorderly was turned into butter by Miss Annie," a witness reported.

Once "Aunt Anna," as she was sometimes called, was trying to console a soldier who was not responding to treatment. She had sat and held his hands for days before he finally told her he did not want to live because his pilot brother had been killed. She returned, bringing him a present of a poem she had written for him.

Soldiers showed their devotion to Miss Annie by giving her mementos which she pinned on the black cape she always wore. By the time of her death, the cape weighed 15 pounds. It was literally covered with rank insignia from private to lieutenant general, unit crests, qualification badges, and patches from units from World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

One of her greatest admirers was Gen. William Westmoreland. A Fort Campbell soldier reported that when he arrived in Vietnam and reported to the general, he was asked "Howís Miss Anna?" When she was in her final days at the hospital, the general sent her roses every day.

During her last years her health began to fail, partly because she was so engrossed in her mission of teaching Sunday School, preaching, praying and counseling that she would forget to eat and then would end up in the hospital suffering from dehydration. Most of the time a few good meals would revive her and she would go back to her work.

Bill Mabry tells of on night when he was called to the hospital. He was told his aunt was dying and would not last the night. "I rushed to the hospital and when I walked into her room, she smiled at me. Having had similar experience with her, I told the nurse she would be all right. The nurse thought I was being callous.

Two days later, with the help of some glucose and good food, Anna was back at work with her boys.

The army provided a staff car for her visits to the post when she could no longer ride the city bus. Finally, she visited the stockade in a wheelchair.

When Anna Barr died, more than 250 people, including the Fort Campbell general, attended her funeral at Trinity Episcopal Church in Clarksville, Men from the 553rd Military Police serving as pallbearers. She was buried in Greenwood Cemetery. Some of her own words weré read during the service:

"The world is burning up outside- your boys fill the ditch over which civilization is marching to peace. Are you even listening? 0 comfort the broken-hearted; ease the pain of those who have done their best - given their all".

On May 11, 1986, an encasement containing mementos of Mrs. Barr, including her famous cape, was unveiled in the Pratt Museum at Fort Campbell.

Maj. Gen. Burton D. Patrick, commander of Fort Campbell, paid tribute to her: "Although we never knew each other, I was quick to recognize that if there was ever a person she should be memorialized in the annals of history about this great post and the men who came here to serve during those days, it was-íMomí."

Today, in the quiet of this place so steeped in history, we are about to do just that and memorialize this sweet, kind, thoughtful and gentle lady who became 'mom' to those sick in the hospital, and who became 'Aunt Anna' when she stood on a small box at the airfield to convey a message of love to our soldiers departing for a far-away place called Vietnam.

"Yes, it certainly would have been an honor for me to have known her and to have been able to see that twinkle in her eyes- I/m told gentle, strong and caring, like that of an eagle. So . . .the encasement. . . will serve to remind soldiers of the past, present and future that a giant of a person walked these grounds doing a simple and wonderful thing- helping soldiers."

Leaf-Chronicle, May 31, 1992