FNB Chronicles

(page 1)

The Civil War

. . . On The Cumberland Plateau In Tennessee

By MICHAEL R. O’NEAL

Scott County Historical Society Member

(EDITOR’S NOTE— This article, on the Civil War in Scott and surrounding counties, was completed in May 1982 as part of a history course at Middle Tennessee State University. it represents a rare glimpse of how America’s most bitter struggle touched the lives of those who resided in one of the most isolated areas of the country. For the purpose of ease in reading and with the author’s permission, some 140 footnotes have been omitted from this article. O’Neal‘s paper was first published in the Winter and Spring 1986 Newsletters of the Scott County Historical Society and is reprinted here with permission.)

The Cumberland Plateau is the westernmost geographical subdivision of East Tennessee, a 5,000-square-mile upland region which has historically been isolated by steep escarpment walls on the east and west. During the Civil War this unusual area, because of the character of the terrain and residents, experienced some of the most bitter guerilla warfare to have occurred in the state. While having much in common with the rest of East Tennessee, the peculiar isolation of the Plateau made its wartime experience different in many respects. The purpose of this paper is to provide a study of the political, social, and military history of the Civil War in one part of this area, the Upper Cumberland Plateau, which is comprised of Scott, Morgan and Fentress counties.

Although the land which makes up the Upper Cumberland range was not officially opened to settlement until the signing of the Third Treaty of Tellico in 1805, by the end of the eighteenth century there was already a thin and largely unrecorded migration of white settlers into the area. In general, however, westward-moving pioneers opted to bypass the rocky and barren lands of the Plateau for the more fertile bluegrass regions of Middle Tennessee and Kentucky. Though but sparsely populated, civil governments were soon established on the Plateau — Morgan County in 1817 and Fentress in 1823 (Scott County was formed in 1849 out of parts of Morgan, Fentress, Campbell and Anderson counties).

On the eve of the Civil War, Scott, Morgan and Fentress counties were remarkably similar — sparsely populated (the 1860 census figures were 3,519, 3,353, and 3,952) and rural (each of the counties had only one town, its county seat, which was centrally located; these were Huntsville, Montgomery, and Jamestown). Small farms and few slaves were the rule. Although nine percent of East Tennessee’s population was slave (in only two out of thirty-one counties did blacks represent as much as four percent of the total population), on the Cumberland Plateau the number was even less. Slaves in Scott, Morgan, and Fentress counties numbered 61, 120, and 187, respectively. Scott was one of only two counties in Tennessee which had less than one hundred slaves, and the only one in the state which had no free blacks.

There is little to indicate the attitude of the people of the Upper Cumberland during the years of growing sectional strife (Newspapers did not begin to be printed there until the late 1880s). Politically the Cumberlands wavered in sentiment and pre-war election results do not reveal any pattern which would explain the strong Unionist leaning which would become apparent in 1861. One incident which illustrates just how far removed the people of this section were from the current events at this time is in the report of Reverend HERMAN BOKUM, of the Knoxville Bible Society, who was amazed to find people in Scott County who had not heard of the secession of South Carolina several months after the event.

The election of ABRAHAM LINCOLN in the fall of 1860 and his subsequent call for 75,000 troops for the suppression of South Carolina triggered a wave of secessionist sentiment which spread across Tennessee from west to east, erasing the general hope for a peaceful settlement which had been prevalent in the state. Governor ISHAM G. HARRIS determined to carry Tennessee out of the Union, called the state legislature into session to vote on a proposal which called for a convention to consider the future status of the state. In East Tennessee leading political and religious leaders (among them THOMAS W. HUMES, OLIVER P. TEMPLE, Senator ANDREW JOHNSON, First District Congressman THOMAS R. NELSON and HORACE MAYNARD, and fiery editor WILLIAM G. BROWNLOW) loudly denounced this measure and did their utmost to defeat it. The result of the poll taken of February 8, 1861, was "a conservative triumph over radicalism." In East Tennessee eighty-one percent of the vote was against the convention proposal; statewide it was rejected 68,282 to 59,449. The voting results from the Upper Cumberland area reveals that opinion on the question of succession was already firmly decided, with the exception of Fentress County (which, because of its western half, had economic ties with Middle Tennessee); in Morgan County the vote was 488-13 against. In Scott 385-29 against, and in Fentress 334-325 for the convention.

HARRIS, however, was not to be stopped. The Fort Sumter crisis led him to call for a second vote on the question of secession to take place on June 8. This time, however, it seemed likely that popular sentiment might carry an ordinance of secession. Accordingly, East Tennesseeans met in Knoxville on May 30 in a convention of their own to discuss their options; twenty-six counties (469 delegates) were represented, although only Morgan County represented the Cumberlands.

Because every vote was deemed critical on the eve of the June 8 election ANDREW JOHNSON and "Parson" BROWNLOW — both of whom had advocated an independent East Tennessee state in the 1840s—set out on their last speaking tour in a last-minute effort to sway the voters. On May 29 they left Knoxville on horseback for a swing through the Upper Cumberland plateau, addressing crowds at the villages of Jacksboro (Campbell County), Huntsville, Jamestown, and Montgomery, winding up at Kingston on June 7 with both men exhausted. The speakers had evidently been well-received; the following month Johnson got a letter from a Morgan County resident who told him that "you made quite a mark —for the people almost worship you.

Although seventy percent of East Tennesseans voted against secession on June 8, the section as a whole represented only forty percent of the state’s total ballots; when the final tally was made the secession ordinance had been carried by a majority of 108,399 to 47,233. The strongest Union vote was to be found in the Cumberlands: in Scott County it was 521-19 against, in Morgan 630-50, and in Fentress (which displayed a remarkable and dramatic turn-about in sentiment since the February vote)

(Continued on page 4)

(Continued from page 1)

651-128. Violence was reported to have erupted at the polls in the latter. There were only three families living in Scott County who were for secession; according to local legend, as a young man from one of those families cast his ballot he proclaimed his Southern stance by leaping into the air, clicking his heels and shouting "if I lived in Hell I’d fight for the Devil!"

Even though the outcome of the election had been largely a foregone conclusion, the East Tennessee Unionists refused to concede defeat. Denouncing the ordinance of secession ("the most outrageous, high-handed and infamous legislation known to the civilized world," as BROWNLOW referred to it) as the result of force and fraud — a charge which seems to have some merit — NELSON and other political leaders called for another convention to be held a Greeneville on June 17. The chief result of this meeting (attended by only 292 delegates of the Knoxville convention) was a petition drawn up and sent to the HARRIS administration in Nashville, requesting that East Tennessee be allowed to withdraw from Confederate Tennessee (All three counties of the Upper Cumberland were represented at Greeneville).

Governor HARRIS, of course, rejected this offer. Cumberland Gap and the vital East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad, which united Virginia with the lower South, made possession of the region critical to the Confederacy. But HARRIS at first tried to avoid an outright confrontation with the East Tennessee Unionists because of the sensitive negotiations going on with the border states. The Unionists themselves saw little chance of a peaceful settlement; at the Greeneville convention NELSON had advocated "military companies to be raised in every county." Representatives ROBERT K. BYRD (Roane County), JOSEPH COOPER, and S. C. LANGLEY (both of Morgan County) secretly conferred on plans to raise five hundred troops. BROWNLOW would later claim that as early as July 1861 there were ten thousand East Tennesseans under arms, ready to defend the Union.

There were growing signs of outright opposition to the Confederate government. In June 1861 the Scott County Court met in special session and drew up its own secession ordinance. It proclaimed itself the "Free and Independent State of Scott" and sent the document to Nashville. The court admitted that it had no legal basis to secede from Tennessee, but countered that the state did not have the right to secede from the Union. A similar incident occurred in Washington County, where the residents of the Fifth Civil District "seceded" and established "Bricker’s Republic."

Apparently it did not take long for the war to the come to the Upper Cumberland. Word spread quickly though the mountains and allegiances were soon declared; in Fentress County both Confederate and Union military units were being organized as early as August 1861. In his memoirs, Secretary of State CORDELL HULL (who was born in that part of Fentress County which would later become Pickett County) wrote: "I remember old soldiers telling me that everybody of military capability was expected to go to war. It really did not make so much difference which side he fought. He had the privilege of selecting his own side, but he could not lie around the community, shirking and dodging. He had to go out and fight."

Soon after Tennessee joined the Confederacy on July 22, Union men began slipping across the border into Kentucky to join the Federal army. One Confederate cavalry officer (400 Confederate cavalrymen arrived in Morgan County on July 9) reported from the Upper Cumberland: "There can be no doubt that large parties, numbering from twenty to a hundred, are everyday passing through- the narrow and unfrequented gaps of the mountains into Kentucky to join the army. My courier just in from Jamestown says that 170 men from Roane County passed through there the night before . . ." Many of the Unionist political figures also sought to escape across the border before the net got too tight: while MAYNARD made good his attempt, NELSON was captured seeking to slip through Cumberland Gap and G. W. Bridges (Third District Congressman) was apprehended just north of Jamestown.

While the men from the Cumberland district would not have needed the services of a guide, many other East Tennesseans sought the help of a "pilot" to lead them into Kentucky. These were local men of daring whose intimate knowledge of the region enabled them to direct thousands of fugitives through hostile patrols to safety. Among the most successful of the pilots were DANIEL ELLIS ("the Old Red Fox") from Carter County; JAMES LANE, of Greene County; WASHINGTON VANN and W. B. REYNOLDS of Anderson County; and SPENCER DEATON, SETH LEA, and FRANK HODGE of Knox County. Together, these men and others are said to have aided the escape of 15,000-20,000 East Tennesseans. In addition. an estimated six thousand men from the twenty-one western counties of North Carolina crossed over into Kentucky.

The goal of these exiles was Camp Dick Robinson, located in Garrard County, some forty miles south of Lexington. Here, on the rolling lands of a pro-Union farmer, the Lincoln Administration had established a recruiting center to assemble and mold the East Tennesseans into a fighting force which would hopefully liberate their homeland in the not too distant future. By the winter of 1862 five regiments of infantry had been organized at Camp Dick Robinson. Since family members (fathers and sons, for example) and neighbors from the Upper Cumberland made the trek into Kentucky together, it is not surprising that men from one county might be found together under arms. Morgan County residents, for example, comprised the entire roster of Company F of the First Tennessee Infantry Regiment, organized on September 1, 1861. Likewise for Company B of the Second Tennessee Infantry, which was formed on October 20.

By the end of the war thirty-one regiments (comprised of 31,092 men) had been organized from the state of Tennessee and mustered into the Federal army. Thirteen of these were "all-Tennessean" outfits. Most of the military units composed of men from the Cumberlands were generally regarded as second-rate troops because of a lack of discipline and were utilized mainly as garrison soldiers in South Central Kentucky or around the Cumberland Gap area, although some of the cavalry regiments were quite active and effective (particularly the First Kentucky Cavalry, under the command of Colonel FRANK WOLFORD) and many infantry units saw a great deal of service in the latter part of the war (first with General BURNSIDE in the defense of Knoxville and later in SHERMAN’s March to the Sea). One Scott County man wound up in a Ohio regiment which took part in the Battle of Gettysburg; he later described to his grandchildren the way in which blood flowed down the hillside following Pickett’s charge on Seminary Ridge.

The flight of men across the Kentucky border was substantially increased after April 1862 when the Confederacy began enforcing the conscription law in Tennessee, although military leaders complained that troops raised from East Tennessee were unreliable and virtually useless. The complaint seems to have been well-founded, because by July 1863 some 36,000 men from Tennessee and North Carolina had deserted.

On July 26, 1861, General FELIX ZOLLICOFFER, former Whig leader and Nashville newspaper editor-turned solider, was appointed by Governor HARRIS to command the East Tennessee region; his orders were, simply: "Preserve peace, protect the railroad, and repel invasion." ZOLLICOFFER did not relish his task. Although he was anxious to preserve the peace (even to the point of permitting BROWNLOW to continue printing his vitriolic Whig), he saw the military situation in East Tennessee as a serious one. To maintain Confederate control over the 13,112 square miles of the region he had only 11,500 raw troops at his disposal, and over half of these were of necessity garrisoned at the strategically vital Cumberland Gap. With the remainder he was to somehow block the Federal forces which were bound to come eventually, crossing into Tennessee by one of several roads along the two-hundred-mile-long section of the state’s northern boundary. ZOLLICOFFER complained: "You can’t expect me to hold 43 gaps in front of me . . ." Nevertheless, soldiers were set to work filling in mountain passes with timber and rocks; by November the state line had been fortified from Jacksboro east to Cumberland Gap.

One area, however, was still left open and largely undefended — the Upper Cumberland Plateau. On October 14 ZOLLICOFFER surveyed the area and reported: "This section of the country is in perilous condition." The reason for his concern was the existence of several rough roads (four in Fentress County and two in Scott) which, because of their remoteness and inaccessibility, were likely invasion routes. Any Federal army which could pass over these trails would find itself favorably located at Knoxville’s "back door." Rather than attempting to defend the broken and difficult terrain, ZOLLICOFFER planned to stop the Federals if they came that way by blocking them at passes along the eastern escarpment of the Plateau, thus leaving the invaders to starve or retreat. By August 1861 the Confederate general had regular cavalry patrols roaming the roads along the Tennessee-Kentucky border watching for signs of an enemy advance; most of this force was stationed in and around Jamestown while another segment was located at Chitwood’s (an old crossroads in northern Scott County, about five miles south of the state line).

One of these units was the Second Tennessee Confederate Cavalry, to which RICHARD R. HANCOCK was assigned. In his diary, HANCOCK made the following observations in late August:

"We found that the majority of men thought this portion of Tennessee had either crossed over into Kentucky to join the Federal army or hid out in the woods. It was reported that before reaching Montgomery that we would meet a considerable force at that place, but they left before we got there. We saw one

(Continued on page 5)

(Continued from page 4)

woman and one child as we passed through the county seat of Morgan County, but not a single man was to be seen... It was raining hard when we arrived at Huntsville, where we took shelter in the courthouse. Scott was a rather poor country, as the people were mostly Union, they were not willing to divide their rations with ‘Rebs’ . . ."

The fall of 1861 passed quietly enough for East Tennessee until November 8, when a small band of Unionists, led by WILLIAM BLOUNT CARTER, a minister from Elizabethton, attempted to destroy various bridges along the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad as the prelude to a Federal invasion attempt. Although the net result of the raid was negligible (the supporting Federal troops were called back at the last minute; those bridges which were destroyed were replaced within a month), the incident caused considerable alarm and excitement among the Confederates in East Tennessee, who finally initiated a crackdown on the Unionists, complete with mass arrests. Amid the wild rumors which were circulating one was to the effect that the Federal army was invading (this was probably spawned by General GEORGE H. THOMAS’ abortive move on Cumberland Gap) through the Upper Cumberland. ZOLLICOFFER wired HARRIS: "A reliable citizen from Huntsville, Tennessee, just in, reports the general impression that the enemy are sending in a force by Chitwood’s from Williamsburg, Kentucky . . ." ZOLLICOFFER immediately organized a small expedition and set out to meet the Federals, but halfway there (Wartburg) word reached him that the report of the invasion was false.

By this time, however, Kentucky’s neutrality (which had buffered Tennessee from invasion) had been breached by Confederate forces under POLK at Paducah, and ZOLLICOFFER elected to go ahead into Kentucky to meet any Federal force aimed at East Tennessee rather than wait for the enemy to come to him. Accordingly, on November 20 he led four and a half regiments of infantry and a battalion of artillery and cavalry (an aggregate of 4,857 men) north -westward from Knoxville through the Upper Cumberland and into Kentucky as far north as the Cumberland River. W. J. WORSHAM, a member of the Nineteenth Tennessee Infantry, wrote of the march:

"Leaving Jacksboro we passed through Wartburg and Montgomery, and crossing the Little Emory River we ascended the Cumberland Mountains again, on whose top we travelled for thirty miles, through as lonely and desolate country as could be found. We passed a residence about every six miles, til we reached Jamestown, the county seat of Fentress County, a small cluster of houses in a rocky, barren county, almost destitute of any sign of life, where the wind’s only song is the sad requium of starvation."

Another rare and interesting description of the Upper Cumberland at this time is provided by the diary of WETWOOD JAMES, who was a member of the Sixteenth Alabama Infantry. JAMES recorded the following observations:

"The order came for moving at last and after two days of hard walking finds our actor at Wattsville (Wartburg) a little German town where the grapes grow and wine is to be had in abundance, and a pretty fair article of the sort too . . . The country here is pretty hilly but not too much for growing grapes & corn, wheat & c(?). There are hundreds of acres planted. I should like to see the vineyards when the fruit is grown. The vines are supported by a framework. Apple & peach brandy & new corn whisky appear to be the principal products of the soil. The people from their appearances judge to be pretty Low Dereck(?). There [sic] dirty, uneducated, and appear to live for their stomachs altogether. The town has an old, ragged appearance, but it does well enough for those who live here. Montgomery, the county seat, is about two miles from here . . . The people are generally Lincolnites and are perfectly horror-struck by the passing of an army through the country. The men left their houses and the women and boys packed up their baggage and were doing the best they could for an early start ‘for somewhere’... I think I saw 20 families ready to move yesterday as we passed by their houses ... We stayed at Wattsville only 2 nites, and started for some place called Jimtown or Jamestown. After travelling o’er the roughest mountain roads for 3 days we finally reached that old, small county seat without a jail or courthouse. There are only a dozen families in the place. We stopped there and winded until now . . ."

On the rainy morning of January 18, 1862, ZOLLICOFFER’s small force met General THOMAS’ equally unprepared army at the Battle of Logan’s Crossroads (also known as the Battle of Fishing Creek and the Battle of Mill Springs). This affair was a rather minor event so far as the Civil War actions went — was of great importance to East Tennesseans, because when ZOLLICOFFER’s army was crushed (the General himself was killed early in the fight), the right wing of the Confederacy’s line of defense in Tennessee disappeared, promoting LANDON C. HAYNES to observe to JEFFERSON DAVIS that "there is now no impediment whatever but bad roads and natural obstacles to prevent the enemy from entering East Tennessee... and putting it in a flame of revolution."

One possible reason why active resistance in the Cumberlands was so slow to organize in the fall of 1861 (in addition to the "leniency" exercised by the Confederates until the November bridge-burning foray) was the lack of arms and supplies. On October 22 WILLIAM B. CARTER, making his way into Tennessee from Camp Dick Robinson to carry out his ill-fated raid, wrote a dispatch to General THOMAS from Morgan County, stating: "I find our Union people in this part of the state firm and unwavering in their devotion to our government and anxious to have an opportunity to assist in saving it. The rebels continue to arrest and imprison our people. You will please furnish the bearer with as much lead, rifle powder, and as many caps as they can bring for Scott and Morgan Counties. You need not fear to trust these people. They will open the war for you . . ."

The organization of Home Guard units (local groups of Unionists organized under state militia laws to act as "armed police" protecting life and property, but outside direct Federal control) in East Tennessee is usually considered to have originated on September 14,1863, when General STEPHAN A. HURLBURT, commander of the XVI Corps, Army of the Tennessee, issued General Order Number 129, which defined such units and their responsibilities, but a military organization of this nature was operating in the Cumberlands long before this date. Among the papers of the late Judge MITT ROBBINS of Scott County is a rare written record from the Civil War period, the "charter" of that area’s home guard unit. Dated December 28,1861, and appended by seventy-four signatures, the text of the document reads:

"We the undersigned agree and pledge ourselves to each other in a covenant and by our oaths to unite together in a company by the name of a home guard to protect our homes, families, properties and liberties and our neighbors and their properties and liberties and also to protect the constitution and the union and not to interfere with any persons or their property or liberties that we do not consider interfering with us or ours and for our government we bind ourselves to be controlled and governed by any person who a majority of our company may select for a captain, and each of us binds ourselves to remain with and not withdraw from the company without the consent of our captain or a majority of our company, and we also bind ourselves to keep a profound secret of all matters concerning our meeting places and times of our meetings, and what may be done by us, or any of our people. In defense of our Rights, and if any of us shall prove to be traitor, or do anything that may conflict with this obligation he shall be dealt with at the discretion of our Captain and company and also to correspond with all other companies in Scott County of the same obligation. The witness whereof we have subscribed our names."

The Home Guard was apparently a loose-knit yet well-informed association of neighbors (often complimented by regular enlisted soldiers home on leave) hiding out in backwood areas who banded together to harass any Confederate forces or outlaw groups which entered the area. Minor skirmishes and running battles in the mountains occurred quite frequently, although few reports concerning them are to be found in officials records. Such hit-and-run tactics as those practiced by the Home Guards, while not a serious military threat to Confederate forces, were undoubtedly galling, and no doubt contributed greatly. to the bitterness of the fighting on the Cumberland Plateau. HOGUE wrote: "When a man belonging to one side was killed, the other side was anxious to retaliate. For every deed of cruelty the perpetrators had their excuse at the time. Both sides have their stories."

Nevertheless, such tactics represented the only means of active resistance available to the outnumbered Unionists, and as time went by they were to become increasingly proficient in their efforts. As WHELAN observed: "Guerilla warfare was nothing new to the people of the Cumberland Mountains. Their forbearers had been trained to such fighting by Indian warfare and had continued the custom in their personal feuds. It was only natural that this would have been the accepted method of battle in the region."

The first recorded incident of this kind of guerilla warfare took place around noon on February 2, 1862, in the mountains of northern Morgan County, when Confederate cavalry clashed with an estimated 100-300 Home Guards. In this action, which, incidentally, happens to be the first military engagement of the Civil War recorded to have taken place within the borders of Tennessee, the Union men suffered a loss of six men killed. In another typical action which took places on March 28,1862, a detachment of the Third Tennessee Confederate Infantry and a squadron of cavalry was sent out from Knoxville to subdue the armed men in Scott and Morgan Counties. The officer in charge of this expedition later reported that from Huntsville to Montgomery "the column was fired upon all along the march by small parties from inaccessible points" When the Confederates reached the valley of Brimstone Creek (southeastern Scott County) a regular fight developed, last-

(Continued on page 6)

(Continued from page 5)

ing half an hour, in which they lost five killed and twelve wounded; the Home Guard losses were listed as fifteen killed with seven taken prisoner.

Another account which provides a firsthand look at the actions of the Home Guards is given by EDWARD J. SANFORD, a noted Knoxville industrialist who, accompanied by several other men under the guidance of a "pilot’, was attempting to slip into Kentucky in April 1862 to avoid conscription into the Confederate army. He later wrote:

"One incident of the trip will show what manner the people of Scott County were organized to resist their enemies. They were thoroughly loyal to the United States and both determined and active. Through one of the narrow and deep values among the hills over which we travelled, runs New River. Usually it is little more than a creek, but at that Spring-time because of the heavy and steady rains, it was a formidable stream. When arrived on its southern bank we could find but one small canoe; and knowing that it would be imprudent to wait until the whole company could be carried in it over the river, the guns and provisions were placed in the boat, and all who could swim jumped in and breasted the waters. Upon the hillside about the fourth of a mile in front of us, could be seen a small cabin, and as our guide said the occupant was a Union man, we did not hesitate to approach it. We saw no one about the house until one of our guns, in being placed in the canoe, was accidentally discharged. Immediately a man ran from the house to the stable, mounted a horse and rode rapidly up the hillside. We thought this a suspicious circumstance, and on reaching the house and making known who we were, it came to light that the horseman, in the belief that our company was one of the rebels, had sped over the hills to inform the "Home Guards" of which he was a member, and that they would probably fire upon us from every convenient spot, or as it was commonly termed "bushwhacked" us. But upon this a woman of the family went ahead of our party, and let the "Guards" know their mistake; and the wounds or death they would have inflicted upon us were averted . . ."

There are several other stories concerning the activities of the Home Guards, the most famous one (still talked of today) being their surprise night attack on a Confederate cavalry patrol which had bivouacked at a cabin on the Big South Fork River. Seven of the men killed in that skirmish at the mouth of Parch Corn Creek were buried there in a shallow grave surrounded by a rock wall that is still standing.

The period from the Battle of Logan’s Crossroads (January 18, 1862) until the fall of 1863 — when Federal forces occupied East Tennessee — probably represents the hardest time experienced by those who were living on the Cumberland Plateau during the war. In this year-and-a-half span the region became a gloomy non-man’s land between the Federal and Confederate forces, where bands of armed men from both sides roamed freely, spreading violence and bloodshed. Lawlessness led to a suspension of civil government, churches, schools and businesses.

DAVID SULLINS, in his autobiography, Seventy Years in Dixie (1910), described the general conditions existing in East Tennessee at this time when he wrote:

"The land was full of robbery and murder. Bands of the worst men seized the opportunity, scoured the country by night, calling quiet old farmers to their doors and shooting them down in cold blood... It was the reign of terror — war at everyman’s door, neighbor against neighbor. Neither property or life was safe by day or night."

While Knoxville and the more settled areas of East Tennessee appeared to exhibit a "comparative quiescence" under Confederate rule, in the rural areas a civil war was erupting. The war in the Cumberlands, especially in its early stages, before the sides were well aligned, was fierce and deadly. No one could be trusted. Beaten paths were avoided. Those men who remained at home during the war were forced to hide out by night as well as day; as one East Tennessean expressed it, "I am afraid to stay home for fear of being killed at any time." In 1916 Hogue wrote: "The old people of this section know what is meant by war. If there is such a thing as the fortunes of war it certainly meant nothing here." More recently, P. S. PALUDIN observed that "In the mountain war the question of allegience was worn as a target over the heart, among armed enemies . . ."

Local histories of the Upper Cumberland contain many handed-down stories which describe the violence of the day. From Morgan County comes the brutal account of one SIM LAVENDAR, a Union man, who was decapitated by Confederate cavalrymen in front of his eleven-year-old daughter. In Fentress County there is told the story of one man surrendering to another during a skirmish, telling him, "I know you won’t kill me." To which his captor replied, "Just see if I don’t!" whereupon he shot the first man and killed him. From Scott County there are tales of beatings and lynchings by night.

Under such conditions, the role of the women-folk became all-important because in the absence of the men it was they who had to protect themselves and what little crops they could bring in, in addition to sending out food to the hiding places of the men or secreting it among the treetops to avoid discovery and confiscation by soldiers or outlaws. If the plight of the women in the Cumberlands was less dangerous (accounts of mistreatment—other than stealing all their food — are rare) than that of the men, it was no less of hardship.

One

incident which occurred in Scott County underscores the hazards of the time

facing women of the mountains. A body of Confederates attacked the HIRAM MARCUM

home on Buffalo Creek one night in 1862. As JULIA MARCUM, age sixteen, was

making her way downstairs to bring her father (who was apparently returning fire

at the rebels) a candle, one of the soldiers broke into the house and confronted

her, threatening her with his bayonet (the man appears to have thought it was

she who was shooting at the Confederates, for the room was dark and he did not

notice several others present).

One

incident which occurred in Scott County underscores the hazards of the time

facing women of the mountains. A body of Confederates attacked the HIRAM MARCUM

home on Buffalo Creek one night in 1862. As JULIA MARCUM, age sixteen, was

making her way downstairs to bring her father (who was apparently returning fire

at the rebels) a candle, one of the soldiers broke into the house and confronted

her, threatening her with his bayonet (the man appears to have thought it was

she who was shooting at the Confederates, for the room was dark and he did not

notice several others present).

Non-combatants also lived in fear. One day a party of Confederate troops appeared at the Welsh colony of Brynyffynon (located on Nancy’s Creek in Scott County) to arrest and try its founder, philanthropist SAMUEL ROBERTS, for aiding Federal soldiers who passed through the area, a practice ROBERTS freely admitted to. They were proceeding to hang him when one of the soldiers asked just who are these Welsh Lincolnites anyway? Another answered that they were British, whereupon the leader of the men said, "Damn it. That alters matters. If we hang Britishers there will be a Hell of a row." The Confederates released the startled ROBERTS and left. On another occasion CORDELL HULL’s father was nearly killed when he was shot in the face by "Yankee Guerillas" for his Confederate sympathies. In Morgan County Confederate troops forced an old man to stand barefoot outside on a cold winter night in an attempt to coax some information out of him concerning the whereabouts of certain Union men.

Although there were no major battles between regular troops fought on the Cumberland Plateau, an exceedingly active form of guerilla warfare was carried on by irregular partisan bands during 1862-63. As early as January 1862 the Confederacy had authorized these organizations, justifying them as "citizens of the Confederacy who had taken up arms to defend their homes and families," and by mid-September eight states had added such units to their military forces. The Federal government, however, refused to endorse them because of their tendency to become bands of mounted outlaws who accomplished nothing other than to terrorize innocent civilians. (The Richmond government was forced to the same conclusion; due to the Confederacy’s lack of control over these bodies they were ordered disbanded in 1864). This was particularly true on the Cumberland Plateau, which became the battleground of the two most famous — or infamous —guerilla outfits, that of CHAMP FERGUSON (on the Confederate side) and "Tinker" Dave Beatty. There were several other bands of these men —mounted on horses, they ranged through the mountains sniping at each other but rarely fighting stand-up engagements —but none which gained the reputation which was acquired by these two men. Local history still relates many stories about the exploits of FERGUSON and BEATTY and their war in the Cumberlands.

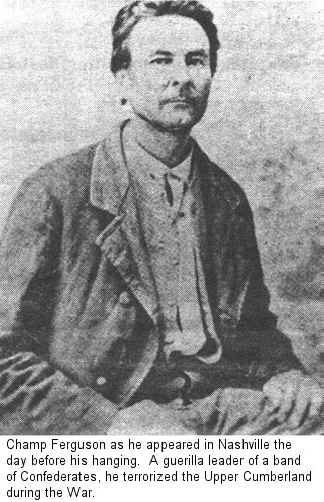

Champ

FERGUSON, in particular, came to be a feared and respected figure in the Upper

Cumberland region. A rough, profane, and physically powerful man, FERGUSON

gained a bloody reputation early in the war for his violent acts against Union

soldiers and sympathizers. Many of the stories concerning him are apocryphal,

such as his cutting prisoners’ heads off and "rolling them down hill like

pumpkins," or his being presented with a Bowie knife by General BRAXTON

BRAGG to "keep up the good work," but the document truth about the man

was just as chilling. In May 1865 FERGUSON, after taking his parole, was

arrested by Federal authorities and brought to Nashville to stand trial before a

military tribunal for fifty-three murders (CHAMP placed the figure of his

victims at one hundred and twenty), including the torture and killing of men

sick in bed. The trial, which lasted from July to September, was eagerly

followed by Nashville society which was fascinated by the grim testimony

presented. Nashville newspapers (such as the Daily News and Dispatch) closely

reported the progress of the trial and transcribed important passages of the

proceedings (Even Frank Leslie’s Newspaper sent a correspondent to

cover the trial of "the Great Mosby of the West"). This testimony

remains as one of the best primary sources for descriptions of the warfare

carried on in the Cumberlands.

Champ

FERGUSON, in particular, came to be a feared and respected figure in the Upper

Cumberland region. A rough, profane, and physically powerful man, FERGUSON

gained a bloody reputation early in the war for his violent acts against Union

soldiers and sympathizers. Many of the stories concerning him are apocryphal,

such as his cutting prisoners’ heads off and "rolling them down hill like

pumpkins," or his being presented with a Bowie knife by General BRAXTON

BRAGG to "keep up the good work," but the document truth about the man

was just as chilling. In May 1865 FERGUSON, after taking his parole, was

arrested by Federal authorities and brought to Nashville to stand trial before a

military tribunal for fifty-three murders (CHAMP placed the figure of his

victims at one hundred and twenty), including the torture and killing of men

sick in bed. The trial, which lasted from July to September, was eagerly

followed by Nashville society which was fascinated by the grim testimony

presented. Nashville newspapers (such as the Daily News and Dispatch) closely

reported the progress of the trial and transcribed important passages of the

proceedings (Even Frank Leslie’s Newspaper sent a correspondent to

cover the trial of "the Great Mosby of the West"). This testimony

remains as one of the best primary sources for descriptions of the warfare

carried on in the Cumberlands.

CHAMP FERGUSON was born on November 29, 1821, in Clinton County, Kentucky, just north of the Tennessee border.

Little is known of his life before the Civil War, but he was widely known on the Cumberland Plateau in south central Kentucky and north central Tennessee. Shortly before the war he moved his wife and daughter to a farm on the Calfkiller River in White County, Tennessee (a few miles from Cookeville). According to local stories, FERGUSON began his campaign of terror after several Union soldiers came to his home while he was away and forced his family to undress and walk down the public road, but FERGUSON himself denied this charge at his trial (However, he apparently held grudges of some kind against several of the men he killed). After the outbreak of hostilities FERGUSON raised a company of men and began "scouting" through the Upper Cumberland, although at one time he was attached to BRAGG’s army and also served as a guide on JOHN HUNT MORGAN’s first raid into Kentucky. He and his men ended the war as part of General JOSEPH WHEELER’s cavalry (WHEELER himself came to testify at FERGUSON’s trial to counter the prosecution’s claim that he was not a member of the regular Confederate forces).

Frank Leslie’s Newspaper described CHAMP FERGUSON at his trial as:

". . . about forty years of age or upwards. He stands erect, is fully six feet high, and weighs about two hundred pounds. He is built solid and is evidently a man of great muscular strength . . . His large, black eyes fairly glitter and almost look through a person. His face is covered with a stiff black beard. His hair is jet black, very thick and cut very short . . . He dresses in a shabby style. A pair of coarse gray homespun pants and a faded gray Rebel uniform coat, over which he wears a very old and greasy heavy coat, a coarse factory shirt and a faded black slouch hat, with good heavy boots, completes his attire. His voice is firm and it is evident that he is a man of iron nerve."

Several of the murders which FERGUSON was tried for occurred in Fentress County. Atypical example was his killing of WASH

(Continued on page 7)

(Continued from page 6)

TABOR. As related by GEORGE THRASHER, a witness of the shooting:

". . . I saw the old man coming up a lane. Ferguson dismounted and went toward him. Tabor was on a horse but got off when Ferguson got up to him. Ferguson soon brought him to where we were, and Tabor was pleading for his life. ‘Oh, yes,’ said Ferguson, ‘You oughtn’t to die, you have nothing to die for,’ all the while getting his pistol out of his belt, and while the old man was beggin’ for his life he shot him through the heart and in the body. He fell after the second shot . . . Frank Burchett (one of Ferguson’s men) said, ‘Damn him, shoot him in the head," and at this Ferguson put his pistol down to the old man head and again shot him. Ferguson looked up at me and said, ‘I’m not in favor of killing you, Thrasher, you have never been bushwhacking or stealing horses. I have killed old Wash Tabor, a damned good Christian, and I don’t reckon he minds dying.’ About this time, Tabor’s wife and daughter came up from the house, screaming and crying . . ."

There were many repetitions of this sort of testimony given during FERGUSON’s trial. Although he denied some killings, he freely admitted to others, claiming that he was only eliminating those who were trying to kill him. Many theories have been put forth to explain his savage acts, which seemingly go beyond the realm of politics. Whether or not CHAMP was a typical mountaineer," as BROMFIELD L. RIDLEY described him, he undoubtedly was carrying out the war as only he knew how. GEORGE THRASHER also relates: "While I was a prisoner, FERGUSON asked me if I didn’t think it would bring the War to a close much sooner he killed all he took. I told him I didn’t know

On October 10,1865, CHAMP FERGUSON was found guilty of the charges placed against him and sentenced to hang. On the morning of his execution in Nashville (October 20), he made the following final statement to the newspaper reporters:

"I was a Southern man at the start. I am yet and will die a Rebel. I believe I was right in all I did. I don’t think I have done anything wrong at anytime. I killed a good many men, of course; I don’t deny that, but I never killed a man whom I did not know was seeking my life. It is false that I never took any prisoners... I had always heard that the Federals would not take me prisoner, but would shoot me down wherever found. That is what made me kill more than I otherwise would have done. I repeat that I may die a Rebel out and out, and my last request is that my body be removed to White County, Tennessee and be buried in good Rebel soil ."

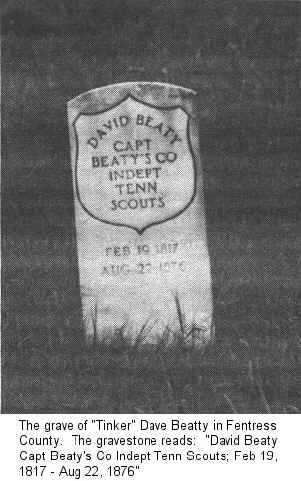

CHAMP FERGUSON’s counterpart and deadly rival in mountain Warfare was "Tinker Dave" BEATTY of Fentress County (the origin of "Tinker Dave" is unknown, but county court records reveal that BEATTY was using it as his legal name for some time prior to the war). If not driven by the near-psychopathic violence which characterized FERGUSON, BEATTY was no less ruthless as a fighter. He claimed matter-of-factly that he only took one prisoner during the war; if there are to be found more tales of grim acts committed by FERGUSON than by BEATTY it is probably only because FERGUSON’s side lost. "Tinker Dave" raised a band of men in February 1862 — largely composed of family and relatives — to protect themselves, but unlike FERGUSON’s guerillas, BEATTY’s men seem to have never roamed far outside the Upper Cumberland area. In A History of Fentress County HOGUE lists several of the minor actions in which they were involved. Also unusual was the fact that BEATTY’s men were one of the few

irregular

organizations which gained recognition by the Federal government; by an Act of

Congress passed on July 14, 1870, they were designated ‘Beatty’s Independent

Scouts" and listed as a part of the Federal force operating in the 1861-65

period. Tennessean's in the Civil War identifies ninety-one men as having

served with BEATTY at some point in the course of the war.

irregular

organizations which gained recognition by the Federal government; by an Act of

Congress passed on July 14, 1870, they were designated ‘Beatty’s Independent

Scouts" and listed as a part of the Federal force operating in the 1861-65

period. Tennessean's in the Civil War identifies ninety-one men as having

served with BEATTY at some point in the course of the war.

The only published personal reminiscences describing BEATTY’s view of the war are to be found in the two days of testimony he gave at CHAMP FERGUSON’s trial, part of which relates:

"I live in a cove in Fentress County, surrounded by high hills. I have known CHAMP FERGUSON for eighteen or twenty years and I saw him a number of times during the War, sometimes accompanied by only a few men, sometimes with quite a large company. During the early part of the War, he was usually with Captain BLEDSOE’s men, who were conscripting, killing, and shooting at Union men in general, including myself.

"About ten or twelve days after the Mill Springs fight [February 18621 several of Bledsoe’s men came to my house and told my wife to tell me I must take sides in the war or leave the country. They took some of my property, some saddles and other things belonging to me, when they left and as they were going down to cross the creek I fired on them, wounding one man and a horse. I was in a field at the time, with my two sons and a neighbor.

"After this they kept running in on us every few weeks, Ferguson, Bledsoe, and others, killing and driving people off. I told my boys that before I would leave home or run away I would fight them to Doomsday and if they killed me, let them kill me. So I took my sons and raised a company of men to fight them. Sometimes I had as many as sixty men, sometimes as low as five. Things went on this way until General Burnside went into East Tennessee, whence he wrote me a letter saying that he wanted me to go out in the mountainforks and bushwhack the Rebels and keep the roads open, saying that I could accomplish much good for the cause in this way. We were not~ getting any pay but the Government furnished us with all the ammunition we needed... [the Confederates] never came into Fentress County without trying to kill us. When the guerillas would run in after us, we had to lie out from them and shoot at them whenever we got a good chance."

Although not a physically powerful man, BEATTY is described as having been a "cunning" individual, who often relied on his wits to escape from dangerous situations. In the Upper Cumberland there are many local tales which describe his quick thinking, such as this incident which Beatty tells of in his testimony:

"About three weeks after the Battle of Mill Springs, Ferguson came to my house along with about twenty other men, some of whom wore our uniform, some had on civilian clothes, and some wore the Rebel uniform. They also had a Union flag with them. I was in a field at the time, which was on the opposite side of the Obed River, about 150 yards from my house. I hollered over and asked them what they wanted. One-of them yelled, We want Captain Beatty to help us drive off the damned Rebels, who are now coming in on us.’ I told them he was down at George Wolsey’s at a log rolling, but that I would go for him, which I did and forgot to come back."

BEATTY also relates one occasion during the war when he and FERGUSON came face to face, and from which he narrowly escaped with his life:

"The last time I saw Ferguson before seeing him here on trial was at Jimtown (the local name for Jamestown), about three weeks after the surrender at Richmond, as I recall. He and five men came up to a house where I was eating supper and demanded my arms. After giving them up, they gruffly ordered me to get on my horse and direct them to the Taylor place.

"After I mounted, they filed three on each side of me. I knew that Champ knew where the Taylor place was as well as I did, and that his design was to shoot me. Champ rode on my left, and I watched him closely. It occurred to me that if I could turn my horse suddenly and slip out, they would not dare shoot for fear of shooting each other, and before they could turn around I could get a good start.

"I resolved to try it, for it was life or death for me, and this was my only hope. I wheeled my horse like a flash, and Champ instantly snapped a cap at me. They then turned and fired about twenty shots at me as I dashed down the road. Three of the shots took effect, one in the back, one in the shoulder, and one in the hip. I, however, got away..

At

this point in telling his story BEATTY stood up and took off his shirt to show

the court the ugly scars left by the bullets. Never to fully recover from his

wounds, "Tinker Dave" BEATTY died on August 22, 1876.

At

this point in telling his story BEATTY stood up and took off his shirt to show

the court the ugly scars left by the bullets. Never to fully recover from his

wounds, "Tinker Dave" BEATTY died on August 22, 1876.

Even though the general impression one has of the guerilla warfare which developed in the Cumberlands as being one of extermination, there is some evidence to suggest that both sides limited their hostilities to persons actively engaged in fighting. FERGUSON’s trial provides instances of where he left Unionist captives live if they would "go home and stay there." A resident of Fentress County, WILLIAM NELSON, testified, "I was a Union man. I have met Ferguson on the road frequently. He always spoke to me pleasantly. There were quite a number of Union men in my neighborhood. I do not know of his having disturbed anyone on account of their politics alone. On the opposite side, there is an anecdote concerning "Tinker Dave" which illustrates the same point. Judge J. D. GOODPASTURE of Fentress County made no secret of his Confederate sympathies, yet he was not molested because he never carried arms for his side. Near the end of the war GOODPASTURE and BEATTY met; as the interview was related in Life of Jefferson Dillard Goodpasture (1897), the judge was "somewhat embarrassed as he did not know how he would be received." After passing compliments of the day, he inquired for the news. "Nothing new," said Tinker, but after a moment he added, "Well, I believe our men did kill a lot of the Hammock gang this morning." In the course of the conversation which followed, Judge GOODPASTURE observed that Beatty had never come to his house. "No, sir," he replied, "I had no business with you."

Although deadly enemies, FERGUSON and BEATTY seem to have had a healthy respect for one another. A somewhat surprising glimpse of this strange, personal war in the mountains is revealed in an interview held with CHAMP FERGUSON by a reporter from the Nashville Dispatch. When asked to give his opinion of his foe, FERGUSON replied:

"Well, there are meaner men than Tinker Dave. He fought me bravely and gave me some heavy licks, but I always gave him as good as he sent. I have nothing against Tinker Dave. He spoke to me very kindly at the court room when he was giving his testimony to me. We both tried to get each other during the war, but we always proved too smart for

(Continued on page 8)

(Continued from page 7)

each other. There are meaner men than Dave."

The only unit of Federal troops to be organized and operated on the Upper Cumberland area during the war was the Seventh Tennessee Infantry Regiment (sometimes designated as the Seventh East Tennessee) to distinguish it from another "7th" formed in West Tennessee). The history of this small band of soldiers is brief but constitutes an important part of the story of the Civil War in Scott, Morgan, and Fentress counties.

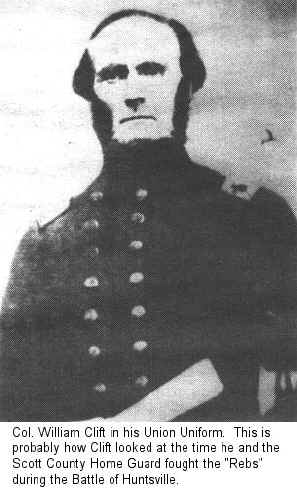

The Seventh East Tennessee Regiment had its inception in the spring of 1862 as the personal project of WILLIAM CLIFT, a resident of Hamilton County whom OLIVER P. TEMPLE once described as "the most ultra of the ultra-radicals." Originally from Greene County (born December 5, 1791), CLIFT moved to Hamilton County in 1825 where he became Chattanooga’s first millionaire as a result of his extensive business and land dealings. An ardent Unionist, when hostilities broke out in 1861 CLIFT actively recruited for the Federal forces at his home at Soddy, where he built earthworks around his house and placed a cannon in the front yard as a symbol of defiance to local Confederate authorities. Several hundred Unionist from lower East Tennessee flocked to CLIFT’s residence for direction (of his own family two sons joined the Union army while another two sided with the Confederacy, as did the husbands of his three daughters).

When Confederate soldiers finally ran CLIFT and his followers out of Hamilton County, the seventy-year-old CLIFT, obsessed with the idea of raising and leading his own group of partisan rangers, made his way north into Kentucky, eluding the patrols sent out by Governor HARRIS to capture him "dead or alive." There he was commissioned as a colonel in the Federal army by Brigadier-General GEORGE A. MORGAN, who authorized him to organize loyalists in Scott and Morgan Counties "in order to annoy the enemy’s rear.

CLIFT

arrived in Scott County on June 1. Establishing his headquarters at Huntsville,

he immediately began enlisting recruits for the Seventh East Tennessee. Most of

these men were from Scott, Morgan, and Fentress counties (the members of the

Scott County’s Home Guard were sworn into this second outfit), although the

company’s muster rolls reveal that several men walked as far as two hundred

miles to join up. Throughout the summer of 1862 CLIFT directed mounted patrols

to cover the Upper Cumberland which, although affording him little more than

moral support to the residents of the area, did report engaging in numerous

minor skirmishes. Meanwhile, CLIFT utilized some of his men to "fortify an

eminence" southeast of Huntsville.

CLIFT

arrived in Scott County on June 1. Establishing his headquarters at Huntsville,

he immediately began enlisting recruits for the Seventh East Tennessee. Most of

these men were from Scott, Morgan, and Fentress counties (the members of the

Scott County’s Home Guard were sworn into this second outfit), although the

company’s muster rolls reveal that several men walked as far as two hundred

miles to join up. Throughout the summer of 1862 CLIFT directed mounted patrols

to cover the Upper Cumberland which, although affording him little more than

moral support to the residents of the area, did report engaging in numerous

minor skirmishes. Meanwhile, CLIFT utilized some of his men to "fortify an

eminence" southeast of Huntsville.

By August 1862 word had reached Confederate authorities in Knoxville that an enemy force had been assembled in Scott County and an expedition was organized to breakup the "annoyance"; on the morning of August 11 some three hundred cavalrymen and six hundred infantrymen under the command of Captain T. M. Nelson left the town of Clinton and marched westward onto the Cumberland Plateau.

Shortly before eight o’clock on the morning of August 13 CLIFT’s picket line was driven back into his "fort" by NELSON’s advancing skirmish line, and by nine the "Battle of Huntsville" was well under way. It was only then that the Union men discovered that CLIFT’s choice of a site for the fort was a poor one; the old colonel had taken for granted that any force attacking him would be unable to scale an adjacent ridge, higher by some two hundred feet, but the enemy had done just that and was, in fact, overlooking the fort and firing downward into it. At the sight of such overwhelming numbers opposing them, most of the 250 men of the Seventh East Tennessee simply turned and fled in "wild confusion" down the back slope of the hill toward New River. Had it not been for CLIFT (who was suffering from a chronic attack of diarrhea that day) and a handful of men who remained behind and fought a delaying action for almost an hour, allowing the rest to escape across the river and into the mountains, the entire regiment would likely have been captured. During this almost comical engagement there were no reported casualties to either side.

Having dispersed the Unionists with the capture of most of their arms and supplies, the Confederates moved into the village of Huntsville and looted it; according to one local account during the two hours they stayed there they made a special effort to locate the impertinent members of the County Court who had sent Scott County’s "seccession ordinance" to Nashville.

Apparently it took some time for CLIFT to regather his company; the Official Records notes that the Seventh East Tennessee was not back on patrol until October 1. CLIFT continually wrote to his superiors asking for more arms and equipment. In a letter to ANDREW JOHNSON, dated December 18, he asserted that "I am by the musket as David was by his sling." In a requisition sent to General WILLIAM S. ROSECRANS four days later he states that, in his opinion, "one hundred bold, dashing horsemen could hold off four thousand Rebels in the mountains, if they were properly supplied."

Then, on December 26, 1862, for reasons that are not made clear in the regimental records, CLIFT received orders from Washington relieving him of command and ordering that the Seventh East Tennessee be disbanded, its soldiers being transferred to the Eighth and Tenth Tennessee Infantry Regiments. This directive produced "considerable disatisfaction" to everyone concerned, with the immediate result being that many of the men deserted (the Seventh had moved north of the Tennessee border — into Wayne County, Kentucky — in November) or went home, while an indignant CLIFT sought to find out why his regiment had been taken from him — even to the point of writing President LINCOLN about the matter. Another person with whom the idea was less than popular was Colonel FELIX A. REEVE, commanding officer of the Eighth Tennessee, who complained that "at least one fourth of the (Seventh) regiment might be mildly denominated a drunken, refectory and lawless mob . . . Please relieve me of them! I am better off without them . . ."

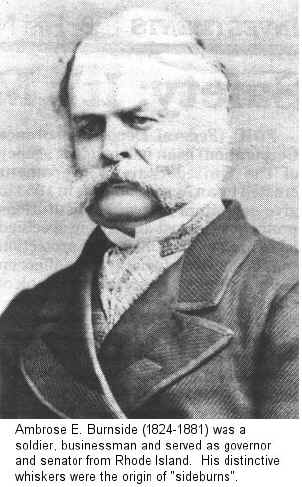

Meanwhile, in late January 1863, CLIFT and his officers traveled to Nashville to present his case to General ROSECRANS, head of the Department of the Cumberland. That officer, however, had his hands tied at the moment, being preoccupied with driving BRAGG’s Confederate army out of Middle Tennessee following the Battle of Stones River. Next, CLIFT went north with his grievances to Lexington, Kentucky, where he met with General AMBROSE E. BURNSIDE, newly appointed commander of the Department of the Ohio. Burnside was somewhat confused because he could find no record of any Seventh East Tennessee Infantry, but issued orders for the transferred members of that unit to be restored to CLIFT’s command — and then countermanded the order three days later. Finally came a confusing series of orders which directed CLIFT to gather whatever he could find of his regiment and move them to Camp Nelson (a few miles north of Camp Dick Robinson) to regroup and reoutfit. There they went into quarters on May 27. At this point, General BURNSIDE sent one of his administrative assistants to Camp Nelson to find out exactly who and what this troublesome unit was. That officer was not impressed with what he saw; he later described the Seventh East Tennessee in a nineteen-page report to BURNSIDE which provides an unusually detailed, contemporary account of the "soldiers" from the Upper Cumberland. Colonel THOMAS R. BRADLEY, the assistant aide, wrote in part:

"Upon my arrival at Hickman Bridge I found the enlisted men who were guarding it belonged to the Seventh East Tennessee Volunteers. I inquired for the commanding officer of the regiment and was sent to various places designated as his Hdqtrs but he could not be found at this time. It was quite impossible to distinguish officers from enlisted men as all were dressed alike in Private apparel and each acted upon his own authority. All looked upon me with very suspicious glances and they appeared somewhat stalled to observe a person in their midst assuming the responsibility of a dictator. Having found Clift the following day I inquired for the regimental papers and was ushered into the adjutant’s office —a small cooper shop — in surveying the contents of which I discovered ordinance and commissary stores, regimental books and papers, stave barrel hoops and a general assortment of merchandise most successfully mixed... It was not known how many men were present for duty but the adjutant’s office was thronged with inquisitive countenances; several persons were armed with revolvers and their time was much taken up in priming them and examining the locks. When a query was put to Clift it was generally answered by one of the men for him, and in some instances disputes arose between officers and men as to who was right. Discipline and manners were entire strangers to the party... I took charge of all the books and papers belonging to the regiment and proceeded to examine them but could make very little sense out of them. CLIFT had lost his papers at Huntsville... The records were very imperfectly kept and incorrect, in almost every instance from the fact that there are not two persons in the entire organization possessed of a common education... The men had been allowed to go into one company today and another tomorrow . . . deserters from the 7th should not be treated as’ such for it is a matter of doubt as to whether they ever heard any regulations read upon the subject, and on account of their ignorance and the irregularity of the affairs of the regiment they should not in justice be held responsible. I would respectfully suggest that they be permitted to remain as they are, unrecognised and unpaid . . ."

On the basis of BRADLEY’s report, BURNSIDE ordered the disbanding of the Seventh East Tennessee, effective July 31, and so the brief career of Colonel CLIFT’s "bold, dashing horsemen" from the Upper Cumberland came to a close. As for CLIFT himself, the stern old Presbyterian never commanded troops again, but he continued to serve in the army. In the fall of 1863 when BURNSIDE’s army in Knoxville was cut off from GRANT’s main force at Chattanooga, CLIFT offered his services as a courier to deliver dispatches. While engaged in this activity he was captured on October 4 by Confederate cavalry (ironically, under the command of one of CLIFT’s sons). Interned for a time in Atlanta, he escaped in January 1864 and made a long, arduous trek home through the dead of winter. His health broken, and partly blind, CLIFT’s military days were over. WILLIAM CLIFT survived the war, however, and regained much of his pre-war prosperity. He died on February 17, 1886, at the age of ninety-one, and is buried in the Presbyterian churchyard at Soddy, Tennessee.

In the summer of 1863 a Federal force was finally put in motion to enter East Tennessee (a long-delayed project of the Lincoln Administration) and the Upper Cumberland Plateau was again the center of attention of both sides, much as it had been in the fall of 1861. As before, the Federals were faced with two possible routes of invasion, either by way of the strongly fortified Cumberland Gap or across the poor mountain roads of the Plateau. Since a frontal assault against the former was not deemed feasible, General BURNSIDE and his aides began to study the problems inherent in moving his twelve-thousand-man army by way of the second route. The problems were many: in addition to the rugged and narrow trails which would have to be crossed there was a formidable logistics obstacle, since once upon the Plateau the army would have to feed itself. Colonel ORLANDO M. POE, BURNSIDE’s chief engineer, made an initial survey of the terrain and reported: "This much I can say now: the maps we have are perfectly worthless . . ."

Nevertheless, the preparations were made and on the morning of August 21 the Twenty-third Corps (Army of the Ohio) left its camps around Lexington, Kentucky, and began to march south, its progress hindered by a blistering heat wave. Searing heat, however, soon gave way to unseasonal and torrential down-pours, transforming the roads into a quagmire under the tramping of thousands of feet. Hundreds of wagons had to be pulled and pushed by hand through the mud as the army made its way slowly from Somerset to the Tennessee state line. To ease the bottleneck passage of the troops over the Plateau, Burnide —on the advice of Colonel CLIFT and several Home Guards from Scott County, whom he had obtained as guides — divided the army into two columns, one of which moved into Tennessee by way of Chitwood’s and Huntsville to Montgomery, while the other advanced to the latter

(Continued on page 9)

(Continued from page 8)

by way of Jamestown over the Monticello Road. BURNSIDE himself accompanied the first column as it passed through Scott County, dividing once again to facilitate the crossing of New River and then making its way up the valley of Brimstone Creek to Hamby Gap and thence into Morgan County.

Under ordinary circumstances the way that Burnside deployed his troops and spread them out across the Plateau would seem to have been an open invitation to Confederate attack, and there apparently was some concern on the part of the officials in Washington (recalling, no doubt, BURNSIDE’s propensity for disaster, such as the Fredericksburg debacle) and in Middle Tennessee, where a worried General ROSECRANS, pushing BRAGG’s Army of Tennessee southward to Chattanooga, continually asked for news of BURNSIDE. However, the danger was more imagined than real for the Confederates did not have the manpower in East Tennessee to block the invasion. Word had reached Knoxville as early as August 21 that the Federals were on the march, but Confederate authorities there could do little more than send out cavalry patrols to hinder the enemy’s progress.

Altogether it required twelve days for the Twenty-third Corps to cross the Cumberland Plateau. Describing the experience in a letter to his wife, LEANDER McKEE, a member of the Fifteenth Illinois Infantry Regiment, stated that:

" . . . it was not a very easy task I can assure you. the Rebs had heard there was a Yankee force in the mountains and sent a force of 3000 men (probably a rumor only; no verification in Official Records) out to Montgomery (a small town in the mountains) to drive us back but the Yanks would not drive worth a d_ys [?] they went back to Knoxville and reported the mountains full of Dammed Yankees said that they held every pass was on every road in fact such an army was never known as there was in the mountains, it is no wonder they thought we had a large army for we was on every road . . ."

Despite the difficulties encountered, both columns of BURNSIDE’s army, having crossed 112 miles over the Cumberlands separated by as much as 30 miles, entered the village of Montgomery on August 30 at the same time. The hardest part of the journey was over at this point, because from Montgomery it was but a very short march of a few miles to Emory Gap, where the Federals would leave the Plateau behind and enter the Great Valley of Tennessee. The following day BURNSIDE sent the following dispatch to Washington: "Advance arrived here yesterday, main columns just coming in. Thrown out skirmishers fourteen miles on Kingston and Knoxville road. Skirmishing commenced near the forks of the road and has been going on ever since . . . Up to this point the opposition of the enemy has been tribling, but the natural obstacles have been very serious. Men in fine spirits but teams much jaded. We have had terrible roads."

Although the Federal troops marching through the Upper Cumberland probably did not receive a warm welcome like the triumphal reception they were to get upon entering Knoxville on September 3, they were undoubtedly hailed by what little population was present in the mountains. Certainly the event made a deep impression on local residents as many stories have been handed down by those who "came out" to watch the endless line of blue pass by. One such recollection is by a woman who remembers as a child seeing General BURNSIDE sitting on a log outside the post office in the hamlet of Pine Top (now Sunbright), writing out a receipt and giving it to her mother for some cows that the troops had requisitioned. There are also accounts of men (originally from the area, but who had escaped into Kentucky) who were seeing their homes and families again —albeit briefly — for the first time in two years. On the flyleaf of a record book in the Wartburg Presbyterian Church someone wrote: "The Yankees came through here late in August 1863."

If there was general gratitude for the presence of the Union army in East Tennessee, there was also some mild indignation. As expected, forage turned out to be a serious problem for BURNSIDE’s army, and many "raiding parties" — some authorized and some not —had necessarily been sent out along the line of march to seize what they could, thereby increasing the hardships of a people in an area where food was already scarce. On August 28, for example, some of the Federal soldiers appeared at Brynyffynon and made off with one hundred bales of hay, leaving SAMUEL ROBERTS with forty. Later in the same day another patrol came back and took the remaining forty bales. On this subject LEANDER McKEE admitted to his wife: ‘When you hear people talk of the many outrages committed by the rebels you can tell them the Union Army is just as bad. We have met with a hearty welcome in E. Tenn. the people have treated us with great kindness and we have robbed them in return."

Nevertheless, by the fall of 1863 —with GRANT’s victory at Missionary Ridge and BURNSIDE’s defense of Knoxville at the Battle of Fort Sanders — the Confederacy’s grip on East Tennessee was broken for good.

CHARLES FAULKNER BRYAN, in his study of the Civil War in East Tennessee, contends that for the civilian population the summer and fall months of 1864 were the most trying because reduced Union troop levels in the state left East Tennessee more vulnerable to marauding Confederate guerillas and outlaws. THOMAS B. ALEXANDER asserts that backwoods lawlessness went from "bad to worse" in 1865. While both of these views are certainly accurate in describing the general conditions which existed throughout most of East Tennessee at the time, there is a reasonable amount of evidence to suggest that by the fall of 1863 the worst of the war was over for the Upper Cumberland Plateau.

With the Federal occupation of East Tennessee secured, the strategic importance of the Cumberlands was nullified, and since the barren region was useless to either side for forage, the isolated uplands seem to have been left alone to regain their pre-war status of neglect, as the military operations of the war shifted to the east and south. SAMUEL ROBERTS complained that the only persons who raided his farm in Scott County in 1864 were Federal troops passing through. On September 5, 1864, a cavalry officer reported to General THOMAS in Nashville from his position on the Kentucky-Tennessee border: "Beatty (Tinker Dave] knows of none (Rebels] in Fentress. There are none in Overton and from what I hear, none about here ..." Another sign of recovery for the Cumberlands was the sporadic operation of the local government: in October 1864 the Morgan County Court met for the first time in two years.

While a respite might have taken effect on the Cumberland Plateau, the war continued in its fury throughout the rest of East Tennessee and the tempo of Confederate guerilla activity intensified during the final months of the conflict. It became necessary for Federal troops to clear away all of the timber and underbrush for one-half mile on either side of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad to prevent constant sniping and demolition attacks. In the fall of 1864 concerted Confederate drives pushed Federal control in Upper East Tennessee as far west as Strawberry Plains, necessitating Governor ANDREW JOHNSON to call out the state militia (amid some protest from Middle and West Tennesseans) to aid in reversing the enemy’s gains. The lingering warfare in the mountains of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina was indeed a troublesome problem for the Federal forces. General WILLIAM T. SHERMAN vented his own frustrations on the subject when he said, "East Tennessee is my horror. That any military man should send a force into East Tennessee puzzles me. I think, of course, its railroad should be absolutely destroyed, its provisions eaten up or carried away, and all troops brought out."

Although the Federal army had consistently adopted a "get-tough" policy with regard to bushwhackers (the standing order was that "no quarter will be shown guerillas and robbers; they will be shot down where found") it was apparent by the spring of 1865 that sterner measures were needed. Accordingly, in March an expedition of six crack cavalry regiments ("a fine body of Cossacks," as SHERMAN called them) was organized in Knoxville for a final campaign of extermination in the mountains. Under the command of General GEORGE STONEMAN, this operation – which WHELAN describes as the mountain version of SHERMAN’s March to the Sea – ended organized Confederate guerilla resistance in East Tennessee, although there were a few isolated reports of such activity as late as June 1865.

Following the Civil War there was, understandably, a great deal of harsh feeling toward Confederates in East Tennessee. Especially bitter were the returning Union soldiers, who in some cases sought to redress personal grievances by legal or extralegal means. Two illiterate soldiers from Washington County, upon being discharged from the service in July 1865, sent word ahead that all rebels in their neighborhood "must leav [sic] before we come home or we will kill lintch [sic] them and that without distincktion [sic]." Although the war is usually regarded by historians as responsible for breeding the ill-feelings which would later develop into family "feuds" in certain locations in Appalachia, incidents of early post-war violence seem to have been largely personal matters. A good case in point concerns CORDELL HULL’s father, who, having recovered from his near—fatal head wound by the end of the war, set out to find the man who shot him. After searching through two counties WILLIAM HULL finally located his assailant and, "without ceremony," shot him dead. In writing of his father’s act of revenge CORDELL HULL noted: "Nobody ever said anything against what he had done. No one ever thought of prosecuting."

BRYAN contends that there were few rebels left in East Tennessee by February 1866, This is probably too inclusive a statement;. for well-known Confederate leaders no doubt East Tennessee was too dangerous to live in, but as far as the individual ex-Confederate soldier was concerned, the degree of ostracism exhibited by a community seems to have varied from one area to another. Certainly there is some evidence to suggest that this was the case on the Upper Cumberland Plateau. Available court records from Scott, Morgan, and Fentress counties reveal no civil actions taken against former enemies, as sometimes occurred in several other East Tennessee counties. Although SANDERSON states that many former Confederates were given a "hard time" and forced to move out of the region, others (such as the families of HULL’s parents) were left alone.

Although HULL writes that "Feeling in that border area was very bitter . . . for some time after the Civil War," local histories relate several incidents which reveal that there were some cases of reconciliation. From Scott County there is an interesting account of two brothers who were reunited after both had taken opposite sides during the war; what makes the story unusual is that one had shot and crippled the other in the fighting at Stones River! On the other hand, there are reports of long-lasting enmity. Also noteworthy is the comment made by a former Union soldier from Scott County who wrote, "I don’t like rebels" on the special 1890 Census questionnaire given to him twenty-five years after Appomattox.

Further evidence of the dissension caused by the war is to be seen in the records of the United Baptist Church in Wartburg. In July 1861 the members of the church agreed not to make "political sentiment" a test of fellowship, but the minute book of their meetings sadly noted on February 1, 1866:

"Whereas the past rebellion, having bred in the church a spirit of discord-and caused the church to be dragged as it were to the very brink of destruction, and whereas we as a church in our cold debilitated condition, resolved to: Pass by for the present difficulties growing out of the ‘past Rebellion’ and handle them I no more until God will have blessed us with a general revival of religion."