FNB Chronicles

(page 8)

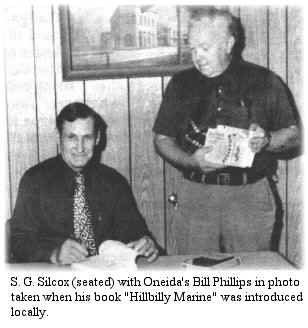

FOREWORD — The article you are about to read was written by S. G. SILCOX in 1987. S.G., or SEIGAL, as we knew him, was born on Black Creek and attended Robbins Elementary and High School. He has many relatives in Scott County and is the author of "A Hillbilly Marine," a very interesting book about his life in Scott County and in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II. The interesting thing about this article of his 7,000 mile tour through the USSR is that he knew that Communism had failed before the world seemed to know it, or before we heard of either glasnost or perestroika. This is pretty observant for a Scott County hillbilly, wouldn’t you think?

— BILL PHILLIPS, Oneida

July 18, 1987 – On the first day of your Russian tour, you board your train at Helsinki Railroad Station at 1 p.m. After the border crossing and one hour difference in time, you will arrive in Leningrad at 9 p.m., local time. This is the first paragraph of instructions furnished by Intourist of USSR and Cosmos International Travel Agent.

Thus

begin our 7,000-mile journey across the USSR. After checking in at Window 31 at

the railroad station and being informed that our train would be on Track Five,

Car Number Two, as luck would have it, Car Two was second from the far end of

the dock. Thus, a long walk; and as told by Intourist USSR travel agents, we

were met by a uniformed person, a middle-aged lady, typically Russian.

Well-built, very neat, and very business-like. She escorted us to our private,

first-class compartment, which was identical to the ones we had ridden all over

Europe for two weeks. Normally, six persons occupy a compartment. But as there

weren’t too many first-class, Helen and I had a compartment to ourselves.

Thus

begin our 7,000-mile journey across the USSR. After checking in at Window 31 at

the railroad station and being informed that our train would be on Track Five,

Car Number Two, as luck would have it, Car Two was second from the far end of

the dock. Thus, a long walk; and as told by Intourist USSR travel agents, we

were met by a uniformed person, a middle-aged lady, typically Russian.

Well-built, very neat, and very business-like. She escorted us to our private,

first-class compartment, which was identical to the ones we had ridden all over

Europe for two weeks. Normally, six persons occupy a compartment. But as there

weren’t too many first-class, Helen and I had a compartment to ourselves.

The first few hours inside Finland were very rural and we saw very few people, and only an occasional small village. Everything was very green and appeared to be low land along the Baltic Sea. Upon arriving at the Russian border, we stopped to change crews — although the attendant in our car remained on until we arrived in Leningrad. The first border inspector arrived at our compartment and was very military appearing, and definitely, to my way of thinking, the rudest person of our entire trip. He did not ask us to do things — he ordered us in Russian to stand up, pointed his thumbs up, speaking and repeating, "Up, up, up," in Russian. I told Helen that I believed he wanted us to stand up, which we did, and he thoroughly searched the compartment. He even unrolled the window shades. He was very precise in all his work, and when he finished, snapped to attention at the door and gave us a snapping military salute. The next gentleman arrived one minute later, very polite, and said in English, "Your luggage please." We took the luggage and laid it up on the seat, unlocked. He went through everything very carefully and closed it. The last piece he examined was a shoulder bag that our daughter Sara had given me, which hung under one arm with strong straps across the chest and across the opposite shoulder. It is a perfect bag for carrying all papers, money and all valuables. That one was the handiest one I saw in our whole journey around the world. This bag had pockets with zippers and pockets within each pocket, zippers everywhere. As he struggled to find each zipper, his helper stood by our door laughing at him, in his frustration of trying to locate each zipper. This destroyed Rumor No. 1 that Russian people never laugh. Hogwash! They are the same as people everywhere on Earth.

At the border, there was a high wire fence running in each direction, very rustic on concrete posts, leaning, looking in a very bad state of repair. Normally, I would have said it was to keep out deer or elk. My first observation were the telephone poles, very old wood and leaning in all directions. All power lines were rustic color, steel-looking and very old.

The first real difference, after traveling in nine countries in Europe and seeing all the nice bicycle paths along, railroads, and highways, suddenly there were only paths through the high weeds, which I observed were for walking, bicycling or motorcycling. Pure dirt with an occasional board or log laid across streams or low spots in the path. We saw very little except timber and a few small dwellings from there to Leningrad.

We arrived at Leningrad, right to the minute, on time. As we stepped from the train, a young man, speaking very broken English, approached us, saying, "Intourist?" I said, "Yes." He grabbed our luggage and said, "Follow me." Here and all through the USSR, Intourist was very much on the ball. As we disembarked from the train each time, by the time we were on the ground, they were there. Very courteous, very precise, very helpful.

As we arrived at our limousine, as the young man had called it, we noticed it was about like a 1966 Chevy. Very well worn inside and a large piece of brown paper in the trunk to lay the luggage on. Definitely, the poorest we had all through the USSR. A fast ride through very light traffic brought us to the Hotel Europeyskaya. The driver directed us to the check-in desk where a lady signed us in. Remember, no tips for the driver — you tip no one in the USSR. You may give gifts, which Helen did many times. Usually, ball-point pens or a cigarette lighter, if they smoked. The check-in lady gave us instructions: "You report to the desk on the second day at 11 (tomorrow) to pick up your passports." All hotels in the USSR kept passports and visas for 12 hours after check-in. The lady at the check-in kept repeating instructions but we could not ask her a question. Finally, we realized this was all she knew in English, so she kept repeating, very slowly, one word at a time. All porters at hotels throughout the USSR were older men. We rode the elevator up to the third floor as all hotels consider the first floor as zero. Only one piece of luggage was on the elevator and Helen got excited. As we reported to the girl at the desk on our floor about missing luggage, she was on the phone trying to locate same when an elderly man stepped from another elevator with her luggage and escorted us to our room.

Tired, I sat down and my first statement was, "Never in my life have I been in a building with so much wasted space!" You have to realize that this was a very old hotel. The ceilings were 15 feet high, the hallways and baths were as large as a small motel in the U.S. Here again, poorest of our trip across the USSR. As I look back, I wonder: "How come the

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 8)

rudest person, the poorest cab, the oldest hotel, all in a matter of three or four hours . . .?"

Hungry, we went to two restaurants in the hotel. All people who know me, know I have only one ear and poor hearing in the other. I literally hate noisy places. Both of these restaurants had wild bands, roaring and shaking the ceiling, and I refused to even go in. We returned to our room, and, of course, those who know Helen know she is always prepared for an emergency. De-hydrated pea soup and granola bars were our first meal inside the USSR.

Russian beds, their coverings and their pillows were far superior to the European hotels. In Europe, all hotels we stayed in had small pillows and narrow pads, very similar to my mother’s old feather bed. To me, very uncomfortable. Try and wrap up on a cold night, which we had some of in Scandinavia and the USSR.

USSR pillows are very large, square and very comfortable. The covers at all hotels and on trains were two large sheets sewn together, one on top of the other — with a round hole on one side which you could easily slip a blanket through. After learning the technique of spreading the blanket out, pulling it between two large sheets, we really had a wonderful cover for cold nights. Then on the warm nights, you can take the blanket out and use only the double sheets. By far, the best of our entire trip.

Early the next morning, by 6 a.m., I left the hotel, as I always do, and went for a walk. First thing you see early in the morning are sweepers sweeping the streets with their long-handled and long-caned brooms. This, at first glance, you feel they do work much better than I realized by watching it on TV. Also, not all sweepers are old women — some are men and, I believe, some young people who may be retarded.

I went left out the door and one block to a park. Upon entering the park, I was approached by three young men trying to talk English but doing a very poor job of it. I believe one wanted to be my guide for the day. I made two or three complete passes around the park, about one block square. Here I observed two things: the grass, very long and shaggy yet very green, and a bird very much like a pigeon only twice the size. This bird had different colors of feathers or spots on its back. I saw these several times in the USSR but failed to get its name. It also acted like a pigeon.

Leaving the park, I walked back past the hotel, noting that the other people were walking in the same direction as I was. When I reached the corner, I realized this was definitely a thoroughfare or main street. People by the hundreds catching streets cars and buses, hundreds walking in all directions. Here, for the first time in my life, I saw large buses run by electric wires overhead. The long connection between bus and electric cables allowed the bus to pull over to the curb as the long connection moved out over the bus on a complete 180-degree angle. It was quite chilly so I headed for the hotel. Stopping at the newsstand, I finally found an English paper, which was the last one until we arrived in Japan. The paper, published in English by a trade union, was definitely a Communist paper. I read articles where 500 Englishmen besieged a US missile site the day before. Now, what does the word "besieged" mean to you? Also, an article how Oliver North had drawn up plans for martial law in the US. After I read this, I thought of our President, Mr. Reagan, who made the statement about Russia being an Evil Empire. Now I don’t give a dam whether you agree with me or not, this article in this paper and Reagan’s statement are dumb beyond words and neither will ever do any good for the human race of man on the planet Earth.

As I arrived at the hotel, I had my pass ready to show, since I had been informed by people that one must have a pass to enter a hotel. Squash Myth No. 2, though in Moscow they were stricter on this issue.

As I entered the hotel, the older bellhop was patting his shoulder and telling me it was cold outside and was encouraging me to go to the bar as he pointed to it and hoist a shot to warm me up. After returning to the room, I entered the bathroom, which was very large and everything was very old. (Squash Myth No. 3.) This old story to take your own toilet paper. Although I must say, on the last day on the Siberian Express we did run out of toilet paper. But all hotels were well-supplied.

We then went to breakfast, part of our package deal. They served the same as all hotels across Europe and Scandinavia.

After breakfast, we went to the Intourist desk to register for a tour of the city. Too late to go that day, so we signed up for a trip to the Hermitage. This was the winter home of all the Czars before the revolution in 1917.

Here, our first lesson on Russian red tape, or paper shuffling, or an excuse to give everyone a job. First, you sign up, then you are given a slip, which you must take to the check-in office. They approve, then you go to the cashier, pay for the trip, then return to the tourist office. They give you the license number of cab out front which will take you to Hotel Leningrad, where all tours begin. There you check in and wait for a tour guide who takes you to the bus, which takes you halfway back to your own hotel, to the Hermitage. At both hotels, we had already learned one very unbelievable thing, and found we had made a mistake by trying to unload all of our foreign currency. No one had told us that all shops in the USSR hotel would not take rubles, their own money. Each shop had a sign, "Hard Currency Only." Hard currency means deutsche mark, Fin mark, Swedish crown, French francs, US dollars, Japanese yen.

To anyone on Earth who has studied art, there is no need to explain the Hermitage in Leningrad. For me, I had never heard of the place. The Hermitage is beyond a doubt the world’s most elaborate display of artwork and artifacts, mostly collected by the rich Czars before 1917. The gold and precious metals of all descriptions are beyond description. I have always loved good art and this is definitely tops in every way. Here you will not see art produced by pouring paints on a dog’s tail and patting dog on head so dog wiggles tail, creating so-called modern art. If you’re ever there, a word of advice: try to get in without a tour guide. There are so many tours and so many people I did not hear one word our guide said. If you can get in, spend the entire day. You may want to come back the second day if you love good art.

After returning to our hotel, we spent some time walking in and out of shops, trying to figure out how the shopping worked. Believe me, it is beyond description, which I will try to explain after we reach Moscow and try to understand the system better.

We went to the restaurant to buy seltzer water and they were able to seat us for the evening meal, as it was then 6 p.m. After being seated, I laid my camera on the table. Very shortly, two gentlemen were seated with us, which is not unusual all through Europe and the USSR. One gentleman was from Wales, who was working there on construction, as were several men we met in Leningrad and Moscow. Most of them were from Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Western Bloc countries. Each made no bones about telling us, when I inquired, why they were there. They all said that the Russian people as a whole have no skills and are not trained to do their work. As the gentleman sat down, I took my camera and hung it on the back of my chair. After we finished eating, we returned to our room. I realized I had left the camera on the chair. I returned only to find it gone. I talked to the maitre d’ and the waitresses, and also went to the front desk. I reported to everyone and checked the next morning and no one had the camera. To me, this ruined our entire trip. I was sick and mad at myself for being so careless. Twenty-four hours later, we went back to the restaurant and were seated 50 feet from where we were the night before. Helen set her purse on the floor, as we were, once again, seated with another couple. After finishing the meal, Helen reached to get her purse and there beside the purse was our camera, minus the cover. Someone had rolled it back from No. 23 to No. 12 and opened it up. Thereby, I lost all the pictures I took in Stockholm and Helsinki.

When I tell this story you will not believe all the opinions that people had and what happened. The suspicious ones who wake up every morning and look under their beds for Communists say, of course, the KGB took it and examined the film. Others say whoever took it got scared and returned it. I do not know the person who placed it there. I believe they had to know Helen and me. My only question is why they did not walk up to us and say, "We found your camera," and give it to us.

Our second day in Leningrad included a complete tour of the city. It was a beautiful city, but on the entire trip I would consider Helsinki, Finland, the nicest city of our world tour. Also, we met a group of ballet performers from South Carolina. A very clean-cut group, which to me looked good in a foreign country.

During one of our tours in Leningrad we met a Japanese couple on their honeymoon. They had been attending Florida State University in Tallahassee and he was a graduate of same and always boosting the FSU Seminole football team. They kept popping up everywhere we went across the USSR. Before leaving Leningrad, I want to mention one thing which surprised me. Knowing we were in a Communist country which confessed to being atheists, I was very much surprised to see in the Hermitage, large and outstanding works of the Christian religion. Christ on the cross, Mary and the baby, and many more.

Throughout the USSR, I saw not one thing condemning or trying to discredit religion, although we were told we were not allowed to bring in or distribute religious material.

We departed Leningrad at 9 p.m., a small inconvenience after we had to check out of our hotel at 1 p.m. They did store our luggage, though. As usual, one hour before departing on the train, we reported to Intourist and I was given the license number of the cab waiting in front of the hotel. The bellhop carried our luggage to the cab and we were driven to the railroad, where we boarded an overnight sleeper to Moscow.

Two people to a sleeper. Thank God’ for small favors — as we learned later, if you are booked on first-class all alone, you have no way of knowing whom you will be sleeping with. A very strange system for an American, but it seems to work.

Arriving in Moscow at 7 a.m., an Intourist man, as always, took our luggage as soon as we stepped from the train and put us in a cab, somewhat better than the one in Leningrad. Arriving at the Intourist Hotel, this one much newer and more modern than the last one, we checked in. Surprised to find that they had a room ready on the fourteenth floor.

Looking out the window, you could see a large part of the city. We went to breakfast and were informed at the front desk that we would have to pay for our first breakfast, as were not overnight guests. But the girl at the entrance to the restaurant refused money and seated us at a table, where we ate cafeteria-style. We saw many Americans and Western Bloc tourists here as we had in Leningrad.

After breakfast, Helen went to the room and I started for a walk. Just as I reached the street, a large fleet of cabs parked in front. A man I believed to be

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 9)

a cab driver stepped from between cabs and said in English, "Want to do business?" I asked, "What do you mean?" He replied, "Do you need any rubles?" I said, "No. My hotel and train are all paid for. I have no use for rubles." He said, "Six rubles for one American dollar." I quickly turned and walked away to the left of the hotel and, of course, I was dumbfounded to believe that I paid $1.50 for one ruble and here I was being offered six rubles for one dollar. He was the first of at least seven or eight people who made me this offer before I left the USSR. I walked two or three blocks, then crossed under the street to the other side, where there were many more shops. I walked into many and watched the way business was conducted. Here, as everywhere in Russia, all businesses, hotels, or any place where money changes hands — in some cases, even salespeople — sitting at modern computers were what we Americans have referred to for years as Chinese Computers, the abacus. It is a square box frame With many rods crossways with wooden balls on each rod.

As I worked my way back toward our hotel, on the opposite side of the street from the hotel, I visited every store or small shop. I walked into a meat market that I am almost sure Dan Rather had on his Special from Moscow two months before we left home, although you must remember many things in Russia look the same regardless of where they may be found. For instance, park benches inside the Kremlin Wall are identical to the ones in far-off Siberia.

Dan Rather said he was told there was very little meat until they were told he was coming to photograph, then they filled the counters and showcases. Now I am quite sure no one told them S.G. Silcox was coming down the street. As I entered no one appeared to notice me at all. I stood for several minutes and watched how the whole thing worked. Remember, no refrigeration or at least no signs of any. The meat, beef and pork, I am sure, 500 to 1,000 chickens. In order really to understand this way of shopping, one should have a drawn diagram. All shops were similar, not only here in the meat market but everywhere, except one that was very small, less than a block from this meat market, and another ‘way down on the Manchurian Border. These two small stores with only a few items were operated like our shopping centers. You went in, picked up the item you desired, and checked out at a register. At the meat market, you got in a line, went by the meat counter, picked out meat, and it was cut the desired size, weighed, priced and laid back on the shelf. I assume it had a number on it. You went across and stood in line, paid the amount; returned to the line, went by the meat counter, handed the butcher the slip. Then he gave you the meat. And you then went down the street, crossed it, and repeated the same procedure at the bread market, and then on to as many stores as required for your daily shopping. To us from the Western World, it is a nightmare beyond your wildest dreams.

As I walked back past the front of the hotel, on the opposite side of the street, I prepared to go underground, again, to get to the other side of the street. Looking straight ahead, I saw what I was sure were the church steeples at the far end of Red Square. I’ve seen them many times in the newsreels, so instead of crossing the street, I went underground and headed towards what I thought was Red Square. This was at least a walk of a block long and when I came out there were a thousand people walking in every direction. I walked to the top of the hill and there in front of me was Red Square. Blocked off by barricades, I could see the long line entering Lenin’s Tomb halfway across the square and disappearing behind a large brick building.

I returned to the hotel and got Helen and then went to make our reservation for the tour of Moscow. Helen insisted that she wanted to go to see the Bolshoi Ballet, so we inquired about tickets and were told the ballet was in New York. Here we are trying to buy tickets for the ballet in Moscow, while the ballet was performing in New York City.

We walked back toward Red Square and when we came out of the underground tunnel we could see the line on the right of us lined up, slowly moving uphill toward Lenin’s Tomb. We walked over near the line and there was a barricade that blocked the entire street going up the hill to Red Square. A police or army personnel was keeping crowds of people back from barricades with a bullhorn. I motioned to the officer with my camera, "Can I take pictures?" He nodded, "Sure." Then he walked over and showed me on my wrist watch that in 15 minutes the barricades would be taken down. As I took pictures of the line, on the top of the hill appeared a very large elderly gentleman in full military uniform, with his chest loaded with medals. I would have thought he would have trouble walking down the hill. A typical military sight, everyone in sight of him with a uniform on was snapping-to, acting like God Himself just appeared. I saw this many times during my brief military career. Just to your right was a large gate entering into, I believe, the back side of the Kremlin. The line of people extended through this gate as far as I could see. I was determined to find the end of the line, so we walked on the outside of the fence in the same direction, often catching a glimpse of the line which I never did find the end of. This line of humans moving very slowly toward the tomb had to be at least two miles long. As we walked, I got a few very good pictures of old women working in the flower beds inside the wall. We finally gave up, went back and went shopping along the street across from the hotel — buying only one item, a treat sold on the street that was much like our Eskimo Pie. Although it was not refrigerated, it was very delicious and very cheap.

Here again, we found food very cheap, contrary to every newscast, every documentary, and every "60 Minutes" broadcast. The USSR was, by far, the cheapest food in our ‘round-the-world trip, Japan and Denmark being the most expensive. In all the hotels we stayed in, one could buy a very good meal with wine or vodka for less than $6. This in Port Charlotte, FL, would be near $l0 to $12. The only thing expensive were the hotels. In Leningrad and Moscow, they were, in fact, about $150 a night in American dollars, with 95 rubles each ruble equaling $1.50 American. Hotels in Siberia were 45 rubles; of course, this included -breakfast and cab fare to and from the hotels. Trains, first-class, with seven nights’ sleep cost 581 rubles, about $850, for two people. Meals on the train were, perhaps, a little cheaper but a much smaller selection was offered. Tea on the train was 12 cents in American money, including a lump of sugar three times as large as our lumps in the United States. No doubt a product of Cuba. Tea was served several times during the day. Clothes and shoes, I thought, were very high, especially the shoes, but after a closer look at home, there was not really too much difference. The tours in each city were from $12 to $18 each with an English-speaking guide.

That afternoon, we went back to red Square and spent at least two hours in the largest shopping center in the USSR This time we bought two items to take with us on the Siberian Railroad — a can of fish and a sack of dried apples, exactly like the ones I ate as a child in the hills of Tennessee. We had been warned to take along lots of food. It took us almost two hours to figure how to buy it, and still we had one heck of time trying to pay for something 100 feet away with no one being able to communicate. It truly is a system beyond belief.

That evening after we returned to our hotel and were preparing to go to the restaurant, I turned on the TV and the first thing I saw was the large military man with all his ribbons and medals, laying a wreath just inside the gate where I had been taking pictures. The wreath was being laid at an eternal flame which was burning very high.

The next morning, early, I walked to Red Square and walked around completely, two or three times. As I walked on the opposite side from the tomb, I saw a gentleman standing, taking pictures. One glance and I knew he was what we refer to as a "Good Ole Southern Boy." I walked up and asked him, "Do you speak English?" Very hesitantly, as if he were afraid I could be the KGB, he grunted, "I do." After a few seconds, I found out that he was from Atlanta, Ga. Then I asked the inevitable question, "Are you people ever going to get I-75 finished through Atlanta?" That broke the ice. He smiled and said, "I hope not." I said, "For God’s sake, why not?" He said, "I'm a contractor and have been working on 1-75 for 25 years and if we finish it I will be out of work." You have to admit that he was a "Good Ole Southern Boy" standing right there in Red Square.

At 10 a.m. we boarded a bus for a tour of the city, which was my best one on a bus in the USSR. Perhaps it had something to do with our English-speaking guide. She was very easy for me to understand. I think it had to do with her tone of voice. We were taken around many squares, as Red Square is not the only square in Moscow. By this time, I had seen so many statues all over Europe that they all began to look alike. We went past the building where Gorbachev worked and the largest hotel on Earth — which I later got a picture of, standing on a bridge which crossed a river. Then we were let out of the bus just below the church we always see in the newsreel at the end of Red Square. We were given a complete history of the church, which is now a museum, and a lot of information about Red Square. Our next stop was across the river, in front of the Kremlin. We were given a good explanation of the members of the Kremlin and of other churches on the front and the side of the Kremlin where all the Czars had attended and were christened and married. All straight history as far as I could tell.

The tour went on, eventually stopping for a 30-minute tour of what I think was a monastery for nuns in the days before the revolution. This is one I still am racking my brain about, trying to figure out what part it played in Russian history and why we were taken to see it. I believe, but I'm not sure, that one of the nuns buried here, and perhaps more, had some part in the revolution. Once we entered the wall we could see many graves all over the grounds around old buildings, but inside this wall everything was a shambles. There were weeds among the gravestones leaning in all directions. Even the path through the weeds and stones was pure dirt and a very un kept place. Why? If anyone knows the real history of this place, I sure would like to hear it.

Our next main stop was at Moscow University. We entered the grounds from the front, stopped a short time to take pictures. Then we drove around most of the University and stopped in the rear of the campus. I was quite impressed by the beautiful flower beds. Here was the only place on our 7,000-mile trip across the USSR where the ground appeared to have been mowed with a lawn mower.

I walked across the street from the rear of the campus to an overlook where one could see practically the entire city. We were told that all couples married in this city have a tradition of coming here immediately after they are married. Sure enough, as soon as we arrived, up drove a car and out stepped a bride and groom, all dressed exactly as they do in the US. I was all puckered up to kiss the bride, but you know Helen. We were driven to what our guide said were factories in the industrial part of the city. All we could see were large concrete buildings. Our guide was quite honest in explaining the pollution problem. It also surprised me that she said they have a real pollution problem, but are

(Continued on next page).

(Continued from page 10)

working very hard to correct it. Throughout all of Russia, I saw many smoke stacks which looked like they were burning coal.

After returning to the hotel, I stopped in front of the hotel where chairs and tables were set up somewhat like a street side cafe in Paris. Here Pepsi-Cola was being sold by the glass, not ice cold but not hot, either. After the glass is used, it’s turned upside-down, then pushed down, turning on a spray of water. Of course, this did not impress Helen. She said this was not a sanitary condition. Glass of Pepsi-Cola, no ice, 36 American cents. On tour, we met a couple from Holland, late ‘20s to early ‘30s. They had traveled all over the world and he spoke a little English. It’s amazing how many people we met who had been to the US. Everyone had been to Epcot and the Grand Canyon. One man told me that Epcot was the greatest show on Earth. I agreed, but he kept trying to convince me. We were glad to hear the couple from Holland was going with us on our first leg of our journey through Siberia. Then they were going south to Peking, China.

Before departing on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, I went to the bread market and bought two loaves of bread. I stood in line figuring out what I wanted, then standing in line paying for bread, and then standing in line to pick up bread. Believe me, it was worth it. The bread was very good, and priced at 26 and 36 cents American money. In the US it would have been three times that amount.

Same routine of getting cab number from the girl at the tourist office. We went outside, got in the cab, went only a few feet and heard other cab drivers yelling at our driver, pointing to the tire, which was flat. The driver unloaded the luggage, got out the spare and tools. Another cab driver put wooden blocks in front of the tire to keep the cab from rolling forward. The hubcaps have a long bolt through the center and into the end of the axle. Observation: if you plan on stealing hubcaps in the USSR, you must have a 9/16th-inch wrench. As the driver put the tire on, I noticed it had a knot as big as the palm of my hands with steel protruding out. I said nothing to the driver or Helen, but I assure you I was holding my breath all the way to the railroad station; I realized we were running late. As we started down the street the cab began to vibrate from the knot on the tire. Helen looked over to me and said, "Something is wrong." I smiled and said, "No, it’s the street." We made it to the train by running behind the porter with our luggage at least a quarter of a mile down the dock. As we arrived at the train steps, we were greeted by a young lady neatly dressed in her uniform. My first thoughts after seeing her was that if Dolly Parton moved to the USSR, she would lose her status symbol overnight. Our cabins on the train were exactly the same as all over Europe. Although our literature and pictures had shown a small sink in the compartment, it was not there.

Twenty miles out of the city, we saw our first real Russian village. I was scrambling for my camera, but there was no need to hurry as we saw hundreds before we left the USSR. When one boards the Trans-Siberian Railroad, here is where you really leave the West behind. At least 20 cars, all second-class but one, we were definitely the only Americans and the couple from Holland were the only other people from the West. There were people from East Germany and other Communist countries. Just outside our compartment were posted the names of all the cities we would be stopping in and the local time and Moscow time, as all trains run on Moscow time.. Also listed were numbers of minutes in each stop, ranging from two minutes to 15 minutes. It was amazing that they worked to such an exact schedule. Of course, being electric trains helped them maintain their schedules.

In order to understand our trip through the USSR, one should first know the latitude and understand the weather and climate. Our most southern point, Irkutsk on Manchurian border is 50 degrees latitude, which is ‘about like Winnipeg, Canada. Our most northern point was Leningrad, 60 degrees latitude, about like Whitehorse in the Yukon Territory. I expected to see desert and a lot of dry land in Siberia, which was completely wrong. In July, everything is green and, of course, the forests stay green the year ‘round. Two things stand out above all others — the endless haystacks and the wild hay. Very similar to what ranchers in our West cut along rivers and valleys. Thousands of people, mostly women, mowing, everywhere along the railroad tracks and as far as one could see, with hand scythes and stacking it by hand. In all our journey, I saw three mowing machines, one being pulled behind a crawler or what we call a Cat with a man riding the mower, and one on a large rubber-tired tractor. I saw one square bailer and one round bailer making bales about the same size as in the Midwest. One field chopper was chopping oats, which were just beginning to turn yellow. I assume this was going into the silo. And potatoes! I did not realize there were enough people on Earth to eat all those potatoes. Every backyard had large plots on the hillside. Occasionally a large field of 50 to 100 acres appeared. From Moscow to Irkutsk there were many herds of dairy cattle being herded by one old couple and a small child or two, and, occasionally, a dog. Compared to the US, we saw very few dogs.

The first two days out of Moscow it rained, so we had a good view of the villages and country roads. All villages have dirt streets and lots of mud. When we were not in a large city, all country roads were dirt with some occasionally appearing to have a small amount of gravel. Those old enough to remember when cities in America first were connected by paved roads, about 1920 to 1928, can picture what rural USSR is today, very similar to the US prior to that time.

On the third day, I awoke and looked out the window and saw a cloud of dust. The roads were dry and a truck was causing dust, just like a rural US country road. Ten miles out of the city, one saw very few cars. Two an hour would be an average. You would see twice as many motorcycles with sidecars. Strange, you see motorcycles with sidecars, with the two people riding on the seat and the sidecar used to carry something else. I saw one man mowing hay on the railroad track loading a sidecar with green hay. There were very few bicycles compared to Europe. Every village was very nearly the same — all homes are logs and rough, unpainted lumber. In all of the USSR, I did not see one private home painted. Several had shutters and were very beautiful with flowers in the windows. All shutters were painted blue. All homes appeared to have electricity and TV, and all had outside toilets. Electricity appeared to be one thing they had, but remember we were traveling along a railroad run by electricity. I saw in the USSR, five atomic plants, four of them in operation and one under construction with large cranes working. We saw several new additions to villages and I believe clusters of new homes on collective farms. All were made of logs or rough lumber and all appeared to have upstairs and all were very small – perhaps 600 square feet on the first floor. In large villages and cities, old and newly constructed apartment buildings were mostly six or seven stories high, all looking the same, except occasionally there would be a brick or a different type from the usual concrete. There were lots of lakes and rivers, clean, similar to Canada’s. All rivers are flowing north toward the Arctic.

Very few people on the train ate at the dining car. At all stops of over seven or eight minutes, many would get off and buy food from stands. Along the railroad docks, one could buy almost any kind of food. Some did not look too appetizing. I bought one small bunch of carrots, very tender and very tasty. There were lots of boiled eggs. I actually saw one woman with a large tub or kettle of cooked potatoes. This tub was at least two feet across and two feet deep. The potatoes were steaming and very hot. She sold them by the scoop, resembling the ones once used in old grist mills to measure grain. Each scoop held approximately one quart. A stiff piece of paper rolled at one end was used to make a funnel type of container. This item sold out in about five minutes. At these stands, one could buy cookies and certain types of crackers that were very good.

There are lots of saw mills all through the USSR. Many had large piles of small logs and brush pushed in which appeared to be waste piles. From what I observed, it appeared the Russians do not know what to do with any item that was worn out or discarded. There were lots of junk everywhere, old crawler tractors, even old buildings, miles of old railroad cars and old railroad steam engines. In all junkyards, I did not see one automobile. Endless miles of tanks of crude oil that appeared to be going from each to west towards Moscow. A fairly good supply of farm implements all looked large and clumsy. Several flat cars in the yards and bulldozers, very large, some new, some old. The railroad station always consists of a long platform, none covered. Most of them appeared to be dirty, perhaps from so many people walking on dirt roads and dirt streets. I took a picture of one which showed a large apartment building in the background and small homes nearby with a grove of trees separating railroad dock and buildings. Under the trees and near the dock, pure dirt was worn slick from people walking and standing under the trees waiting for the trains.

That evening, before leaving this portion of our journey, Helen went to the compartment of our attendant and presented her and a lady who often relieves her at night with a pen and cigarette lighter each. An hour later, the one who worked more at night, knocked at our compartment door and when invited in presented Helen with two postcards of Siberian trains and a bar of soap. This is definitely part of their custom. Regardless of how small a child or how old an adult, when they return with a gift, although they speak not a word of English, the expression on their faces can certainly tell the complete story of the joy they feel.

Four days and three nights out of Moscow, we arrived in Irkutsk at 7:55 p.m. local time, or five hours earlier, 2:55 p.m., Moscow time. At this point, we had crossed six time zones since leaving Helsinki, Finland. I had just reached the top of the steps of the train when I saw a gentleman who had been with us all the way from Moscow and about the only thing I could communicate with him was finding out that he was an electrical engineer. He came running from the dock, grabbing my large suitcase and placing it on the dock. By the time I reached the suitcase, I heard the same thing we always hear: Intourist. I said, "Yes" to a very tall man who had the longest hair that I saw in all of the USSR. In America, it would not have been considered too long. Helen was standing just behind me and he said, "Are you the American couple?" I replied, "Yes." He asked if we had seen the couple from Holland and I told him they were three cars up. He told us to wait and took off running in their direction. A short while after he returned, saying, "I can’t find them." Then he took us outside the station and pointed to a panel truck, saying, "Wait there, I have to find the other couple." Just then the couple from Holland came walking from the other side of the panel truck. 1 was able to yell and get the guide stopped before he went back to the dock. They were such experienced travelers they had gone to the panel truck and had their luggage loaded and waiting for the

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 111

guide and us. The tourist office was closed so I had to wait until morning to present our vouchers for a tour of Lake Baikal, the largest and deepest lake in the world. It supposedly holds one-fifth of all the fresh water on the Earth. Our rooms were very nice, but furnished very plainly. The bathrooms were smaller than usual with a shower that sprayed in the center of the entire bathroom, always wetting everything in the room.

Early the next morning, I was in front of the hotel by 6 a.m., ready for my morning walk. I walked across the street to the park and to the river. I started walking down the river for a least four blocks. In the river, I saw several older men in small boats and one in a rubber raft, fishing. As far as I could see, they were all having my luck fishing. Zippo! As I came back toward the hotel, through the middle of the park, I noticed the same grass all long and definitely not cut by a lawn mower. I was almost back in front of the hotel when I came upon three young men and their coach exercising. First, they were shadow-boxing and running in place. As I approached, they went down on the blacktop and began doing push-ups, putting their bare knuckles on the blacktop instead of the palms of their hands. As I approached, I began shouting orders like a drill sergeant: "Push them up — one, two, three, let’s go!" The smallest one jumped to his feet and ran over with and extended hand and said, "You speak English?" "I sure do." He said, "Are you from England?" I said, "No, the United States of America." You would not believe the smile on his face as he said, speaking very slowly, "Let me welcome you to Siberia." As he and I stood talking, the rest gathered around. They wanted to know where I had been, where I was going, and, of course, what I thought of their country. They explained to me that they were training for boxing. Not including our guide and Intourist personnel, this was my best conference in the USSR.

As I returned to the hotel, there were about 50 young Japanese people in front, doing exercises. After breakfast, I went to the Intourist to present my voucher for the trip to the lake, only to be told that we couldn’t go "today," we would have to wait until "tomorrow." At the same time, the couple from Holland with no voucher paid for the trip and got on with a group of English-speaking people from India. I don’t have to explain that this old Irish Hillbilly was very mad when all they’d say is that you have a voucher and cannot got today, but you can go tomorrow.

After returning to the room, I finally cooled off, but Helen said, "What are we doing to do today?" She suggested that we go shopping. So I went to the front desk to find out where the main shopping area was in the city. Here as always was at famous phrase you can hear all over Europe, "Oh, it is only a short walk." When traveling anywhere outside the US and I hear this remark, I have to laugh because we have been suckered into this so many times and this was no exception. We walked several blocks to the end of the park. As we walked through the park, we noticed three children. One boy, perhaps 10, a smaller boy, and a girl in the park grass where it was long and shaggy appeared to be picking up something from the ground. We watched for a few minutes, then walked over, and to our surprise they were gathering mushrooms. The older boy had nearly two gallons in his bag and the two smaller children had a smaller amount. We tried to communicate with them, but, though they were very nice and were trying to be cooperative, it was almost impossible. So Helen gave each a piece of bubble gum. Then we turned down Karl Marx Avenue toward the center of town. Here we saw more street vendors with vegetables and plants and hundreds of items for sale. I thought these were private booths as vendors, but the next day our guide assured me they were all government-owned. Here we saw the second small store where one could go in and pick out a few items. I would guess there were no more than 20 or 30 items in the store— some fruit, canned goods, green peas, in one-gallon jars. Every meal we were fed green peas that were very tasty. Here was one thing you definitely will not see in the USA: a woman dipping into a 10-gallon can and filling small jars her customers brought from home with what appeared to be clabbered milk. Of course, if you’re not over 60 and not born on a farm, you have no idea what clabbered milk is. Do a little research and find out; it will stimulate your brain.

This was, perhaps, our best day of really watching people and how they shop. As we were tired, we sat down by one of those statues in the park on a bench around a lot of flowers. Near us was a very nice appearing lady with deep red hair, which we saw lot of in the USSR. The women color their hair deep red, whereas in the US they go for blonds. She had two small girls and Helen walked over and gave each of them a piece of bubble gum. And as always, very soon, the oldest girl came over and gave us two small pieces of hard candy. We definitely came out the winner in this exchange as the candy was very good and definitely something new to us. We stopped in the park and bought two bottles of apple juice from a stand. We also bought some type of roll or sandwich that was not too impressive. As we walked back through the park, a man came walking toward us and asked us if we wanted to buy some caviar. We said, "No." He went on, but very shortly was back walking alongside and asked if we needed some rubles. He was more cautious than the rest; perhaps he was new in the black-market business.

After returning to the hotel, we sat down in the lobby and soon four men came in, talking English. Of course, I wasted no time finding out who they were — all from Baltimore, one a priest. They had come through China and were heading over the same route we had just come from. The priest was really a "card" and was really enjoying everything he saw. We talked about religion in the USSR and I told him about the paintings at the Hermitage in Leningrad, which they already had planned to visit. He said, "Isn’t it ironic that they display so proudly the very things created by those they condemn?"

After Helen returned to the room, I was trying to carry on a conversation with a Swiss gentleman when a man sat down on the other side of me and asked if I needed rubles. I said, "No." He got up to leave and the Swiss man jumped up and followed him to the center of the lobby and stopped him right there in the lobby. I saw the exchange of money. This and many other things made me wonder after I got home that maybe the government does not want to stop this black market. Anyone could catch them any time of the day.

The following morning at breakfast we met a woman from Ohio, about 60, who had flown to Japan. She flew over Khabarousk and rode the train three days and nights and was going down to China. I thought we were a little weird taking this trip, but you have to admit she really had lots of nerve. But she certainly seemed to be having a ball. These four men and this woman were the only Americans we saw after we left Moscow until we flew over to Japan.

The next morning at 9, I went to the tourist desk and once again presented my voucher which read the 27th of July, this being the 28th. Here began one of the most unbelievable things on our trip. The lady at the desk motioned to a young lady sitting a few feet away to come over. She introduced us to Tanya, saying she would be our interpreter for the day. She was a very short, plump, well-built girl of perhaps 20 or 22. She escorted us to the parking lot and put us in a car with a chauffeur, and for seven or eight hours we had a private interpreter and a private chauffeur. You would have thought we were Ron and Nancy, or at least a close relative. We headed for Lake Baikal and as soon as we were out of the city we began to see soldiers at every dirt road, leading away from the blacktop. On our way out, we said nothing, but by the time we were returning, seven hours later, we were talking to Tanya about everything. We asked her why the soldiers were there when we went out and not there when we returned. She said she had been trying to figure this out because this was the first time she had ever seen them along the road. She thought that perhaps a very important foreign dignitary had made a trip to the lake that morning. Tanya explained to us that they had a very hard time trying to build blacktop roads due to extreme cold in the winter and the thawing and freezing in the spring and fall. I told her I understood perfectly as I had experienced building roads in Illinois and also drove roads in Alaska.

Our first stop was by a walk path which was blacktop and all the bushes on the path had strings or ribbons tied on branches. Tanya explained that if we tied a ribbon or string on a bush and made a wish and told no one, the wish would come true, of course. After returning home, Helen said it worked. She wished we would have a safe journey home. Only a short distance away we got a view of the lake at a beautiful overlook. Across the lake we could see a few cabins, which Tanya said were summer homes. She said her father had a summer home, but he and her mother were geologists and were gone to work in the country for the summer. She also told us they were college teachers and taught geology. Tanya asked us if we would like to see a rebuilt replica of a frontier fort or village. Of course, we said yes. We drove down a very narrow country road almost identical to a mountain road in Tennessee. We arrived at a group of connecting buildings and cabins, all built of logs. Inside the buildings and inside the yards, protected by log walls, we saw many tools of early Russia. Some were very much like early US. Many different types of toboggans or sleds for winter were kept there. The area where cattle were kept had very low doors. She explained that the natives of 200 years ago were mostly Mongolian tribesmen and their cattle were very small compared to today’s cattle.

The most interesting thing to me was a loom. Practically every piece of this loom was built from branches that had grown in shapes that were required to make the loom work. I have seen antiques and I have heard of antiques, but this thing will always remain in my mind as the most authentic piece of equipment built by man from scratch, as we say in the US. It had a small rug half-finished in place, so it really could work.

After this, we were taken along the lake. We stopped at many places and at one point I walked along a rock beach and stopped to look at a fishing rod with a very large reel that appeared to be working very good. We then stopped at a large hotel overlooking the lake and Tanya went in and tried to get us seated for lunch. They were too busy, so she decided to first take us to a village near by. At first glance, I thought this is not a typical village, as there was blacktop on the streets. I very soon found out that the blacktop was only about one-half block long. As we had seen on the train, dirt streets still prevail, but here the ground did have lots of round stones, as this was an old creek bed and a creek ran nearby. I took a picture of one house that had large blue shutters with the log walls and it did have considerable charm and, of course, window sills full of flowers. Also here, the cows and the goats ran free without a herder and, of course, one had to watch out for fresh cow piles.

After we walked through the village, we turned and could see homes across

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 12)

the creek, which we walked across one a wooden bridge built for walking. As we crossed we saw a lady with two children down by the creek washing clothes on the rocks. The water was very clear and very cold, as it definitely flowed from the mountains in the back. We walked up the creek perhaps a block or two and I began to wonder where we were going and why. Tanya said she wanted to show us the village church. Surrounded by a few trees, the building appeared to be extremely old so we walked inside. It was very strange because there were no pews. Tanya explained, after I questioned her, that this is the way the Russian Orthodox worshipped. The inside was beautiful with large amounts of beautiful artwork, mostly small paintings, two feet and smaller in size.

At our right as we entered was a very old lady, and Tanya warned us that it depends who is there if they will allow you to take pictures. The old lady saw my camera and immediately told me: "No pictures." One could buy a candle, light it, place it on the altar, and say a prayer. As we emerged through the door, I realized that Helen and Tanya were talking to a large man with light red hair and two small girls, about 11 and 9. The 11-year-old had, no doubt, been studying English in school and was trying in every way to communicate with us. With Tanya helping her occasionally, she was really bubbling over because she realized she was talking to someone from the United States. The father spoke no English but was all smiles as the translation went back and forth. Helen gave the girl a Kennedy half-dollar and we had been told that many Russians love to collect Kennedy half-dollars. Helen asked her if she knew whose picture was on the coin. She replied, "Sure. John F. Kennedy." The father gave the girls the equivalent of a quarter to give back to Helen. As we started to leave, I thought I would give them a surprise. I said, "Dosvidanya, pah-kah" (Good-bye until next time). The man surprised me, too —he laughed very loud and said in English, "Goodbye."

We walked a short distance and stopped as Tanya pointed to a new home built of rough lumber, which was definitely the nicest home I saw in the USSR. She said that was the home of the priest. Now here, I am quite sure, a deal had been worked out between the congregation, the priest and the Communist government. I say a priest does not get lumber to build a new home in Russia without allowing Intourist to take visitors into the church. I may be wrong, but if I am I will apologize to Gorbachev, the congregation and the priest.

We walked back to the car through the back alleys. On the hills and backyard were potatoes, and more potatoes. Along the back also were piles of manure thrown from cow pens and goat yards. This village, I estimate, had 200 or 300 homes. On the street, I saw two community wells; there may have been more — dug wells with and open bucket and a rope on a crank. All homes appeared to have electricity and TV.

We were taken back to the hotel and they seated us by the window overlooking the lake. Lunch was very good, costing four rubles each, about $6. We started back to the city and I asked Tanya if the USSR had any service stations. "Oh yes," was her reply, "I will show you one." Twenty miles down the road, she pointed to a small service station about one-half block off a highway. This was the only one I saw in the USSR. I am quite sure that in the big cities the stations are inside large buildings.

After returning to our hotel, and saying good-bye to Tanya and the driver, we once again talked to the priest from Baltimore. He had made the same route that we did that day with another group from India, who spoke English. He said he tried every way on Earth to con the old lady in the church to let him take pictures, even to crossing himself the way the Russian Orthodox do it, but it did not work.

That evening, after dinner, we again met the young Japanese couple who had attended Florida State and were glad we were boarding the same train they were. In fact, we were both in the same car with separate compartments.

The four of us rode in the same cab to the railroad station. Our attendant for the three days and nights was an older woman, perhaps in her late 50s, whom I had a ball with. She could really give the Russian people a tongue-lashing when they did something she did not like. Three young men, who I believe were going to work in the oil fields, got drunk the first night and she really lowered the boom. But after they sobered up, she seemed to be very friendly toward them.

Four army officers came into the car dressed in full uniform. These were not privates. All were about 50 years old. Of course, I could not tell their ranks, but I believe they were either colonels or generals. They did exactly the same as all men in first-class. They immediately went into their compartment and changed clothes, putting on jogging clothes. Every time I saw a gentleman come from his compartment, I thought of the statement Henry Ford said about his Model T Ford — "People can order any color they wish as long as it is black." Same with the Russian men’s jogging suits, any color they wish as long as it is blue.

The second day, for a short time, we were being pulled by diesel engines, although work was being done along the track to install electric cables overhead. Also, the farther east we went, all the electric poles and phone lines and poles were much newer and all were made of concrete. There was very little difference in the terrain, although occasionally there were some high mountains, but all had timber, small brush and grass, lots of fresh-water streams and rivers.

I was always looking for wildlife, but I saw absolutely nothing during our entire journey across the USSR. The only people we could communicate with were a Japanese couple and the last night we went to the dinner together, he gave instructions on how to communicate in Japanese, and some diagrams of trains around Tokyo and other large cities. He had done lots of work on this and it did help in ordering food in Japan.

Our attendants, as I call them, actually have three jobs. Our maid, when cleaning the car and our compartment, wore a grey gown; when serving tea, she wore a neat striped blouse; when the train stopped, she welcomed new arrivals in her light green uniform with wings pinned on the blouse. She told us that she works seven days down from Moscow to Vladivostok and seven days back, then has six days off. I think she and I proved, at least to each other, that we did not have to speak the same language to communicate. Some examples:

·

Standing and looking out the window, we saw a large communal farm; she pointed to the barn and began to moo like a cow; I started to milk a cow by hand — while about 10 Russians of all ages were laughing at us.·

Once on the dock, a passenger brought back fried fish in one of those paper cones. I looked and asked what it was. Our attendant began imitating with her hand a fish swimming in water. I grabbed my imaginary rod and reel and cast out into the railroad track. Everybody on dock thought we were a couple of nuts as I was reeling in the big ones.·

Helen invited her into our compartment and was showing her pictures of our home and our children and grandchildren. Her first question, using paper and pen, was whether our son, Robin, was constricted or drafted into the military, portraying the military by pointing and firing a "rifle" out the window. When we said, "No," she seemed to be shocked and said, "Reagan," and began to fire the "rifle" again. I explained that I had been in the military but our son was not. This definitely surprised her.·

When I showed her our grandson, Aaron, I stood up and began to bounce an imaginary basketball and shooting a basket. Here we saw something that was worth the whole trip through the USSR— she jumped up in the middle of our compartment and began showing us how her grandson played soccer; bouncing that soccer ball off every part of her body from head to toe.

Several places we saw military trucks and in some cities lots of military equipment very similar to our National Guard. But most were larger than our National Guard. Several times I saw tanks on flat cars, some new and some appeared to have been recently overhauled with new bolts in the tracks. Several times on large bridges, soldiers were walking guard. Every time I saw this I always thought of the TV commercial: "A mind is a precious thing to waste." What about the whole human? I was trying to imagine who was going to blow up this bridge 3,000 miles from Nowhere in Siberia. I am quite sure the US Army has men doing the same stupid thing.

On board second-class was a group of East German young men who could talk very few words of English. One stopped me in the aisle of the car and wanted to argue the merits of communism and his first question was, "Why do we fear Cuba?" I said, "Man, I only speak for myself. I have no fear of Cuba and my personal belief is that if we had three or four more like Cuba for the USSR to take care of she would be completely broke in two years." He looked shocked and said, "What do you mean?" I said, "Man, when I pay $1.51 for a ruble, and half the cab drivers in the USSR are trying to sell me the same six for a dollar, then this country has real problems."

Then he wanted to discuss Viet Nam, saying America had no business in Viet Nam. I said, "I agree 100 percent." Then he smiled, and I added, "Of course, Russia had a perfect right to be in Afghanistan!" This seemed to dumbfound him, but he managed to say, "We were invited there." My reply: "Check your history. We were invited to Viet Nam."

Somewhere in the conversation, he asked what surprised me about the USSR. I told him the cheap price of food and rent for apartments. He went into a long explanation of how they kept all items essential to life cheap and had high prices on items that were not important to life, like a car. He questioned me about what I did. As I explained, he tried to convince me that I was only the boss and did no work, but just supervised my men. This ruffled my feathers a bit. I said, "Man, you have absolutely no concept of an American who has a small business. I worked from daylight to dark and saved my money — that’s why I am able to be here talking to you now. His final statement was that we had no business in Grenada. I said. "Let me explain one thing to you. The USSR will never build an airfield close enough to the US to bomb us." He jumped on that very quickly: "The USSR had nothing to do with that. Cuba was building the airfield." Did I ever throw him a line here. I said, "Cuba doesn’t even have a twin-engine Cessna in its air force, so why a two-mile-long airfield?" With that he gave up and turned and walked back into the compartment. As he left, he said, "There is no use for us to talk about Grenada." As I walked back to my car, it dawned on me — what in the world am I doing riding through Siberia on a USSR train, arguing with a Communist?

After about an hour, a young man I had seen with the East German group came into our car and stopped to talk with me. He had a completely different attitude and approach. First, he wanted to know how many American young people had a chance to go to college. I played this one real cool, trying to figure him out. I told him everyone could go if

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 13)

they wished. I explained how many went on scholarships and how one borrowed money from the government with no interest until he graduated and went to work. He said in East Germany one out of every five had an opportunity to go to college and if one failed to qualify he was doomed for the rest of his life, working on unskilled jobs. He talked a great deal about how he had no chance of going to the West. He said when he crossed over to West Germany his money was not worth the paper it is printed on. I tried to act surprised, but did ask him, "Can you cross over the wall?" He said, "Oh, the wall is no problem for me — it’s when I get there I have nothing!"

The next night when Helen and I went to the dining car, he followed us and sat across the aisle and several times made small conversation about food and other small talk. Today, I wonder if he was for real or a KGB agent.

After three nights and two days, we arrived in Khabarousk, a few hundred miles straight north of Vladivostok. This was our final destination before leaving for Japan. As always, as soon as we stepped from the train, Intourist took our luggage and asked if we had seen the couple from Japan. I said, "They are coming down the steps behind us."

Our limousine, as they refer to it in their literature, was about like a Volvo station wagon, very nice and almost new. The four of us were taken to Intourist Hotel, although we were not scheduled to stay in a hotel. Our luggage was stored and we were given instructions as to what time we would leave for the airport. The Japanese couple had to go on to another train to the ship which would taken them to Japan. This was the way we were first supposed to go, but the ship cost twice as much as the plane for the trip over the Sea of Japan. I tried for four months to get confirmation of Flight 695 to Japan, with no success. Although the Russian Intourist agent in Florida gave a telephone number of Airfact in Washington, After two or three calls, I called one day and told him either to confirm the flight or cancel the entire trip. Two days later, I got the confirmation. I was bluffing, but it worked in Russia the same as in the US.

Before leaving for the airport, the Japanese couple and Helen and I went to the restaurant in the Intourist Hotel and had a late breakfast. The hotel here appeared to be newer than any one we had stayed in. Also to my surprise, Khabarousk looked more like a US city than any we had visited. The first thing I noticed were the wide boulevards with grass and trees and median strip. Even most of the buildings appeared to be newer.

We left first for the airport. The Japanese couple followed us to the cab and said good-bye. Of course, everyone agreed it was nice to have someone to talk to. His last words were, "Don’t forget to root for those Seminoles." Same cab and driver to the airport, although we were accompanied by a young lady who spoke a little English and gave us instructions on how to check luggage and fill departing papers. How much money did we spend for souvenirs that were going out of the country? Helen proved she was the last of the big spenders —$52 for souvenirs. We had turned in all our Russian rubles, although it was the same as all over Europe: no exchange would take change, only paper money. Instructions had warned us that it was a criminal offense to bring rubles into the USSR or take them out of the country. Personally, I doubt that the latter is enforced as we were the ones to ask for the exchange desk. Think it over — they are desperate for western money, so why would they want to give us US dollars for rubles?

After turning in our money, we went to sit in a snack bar area and I decided I would like to drink one more bottle of their delicious apple juice. But after counting our change, we found we did not have enough. As we talked, a tall gentleman heard us, walked over and gave us a handful of change. "Here," he said, "I’m flying to Japan and once I board that plane this money is worth nothing. He was an American who now lived in Japan and was married to a Japanese woman who was with him.

The air terminal was very old with high ceilings and the Customs lines were long, as we went into a waiting room which was very old and warm. The main thing they check is the declaration each person filled out when they entered the USSR and all jewelry, cameras, and watches. They seemed to go over Helen’s list more than mine. They wanted to see that she still had her mother’s ring and diamond and, of course, both our watches.

The plane was not brought up to the terminal. We were taken out of the terminal. There were perhaps 150 people, all Japanese tourists, except Helen and me and the American-born but now livingin Japan. We were loaded into a trailer pulled by an old tractor. It looked about like a World War II military truck. The trailer was built in the same style as a fifth-wheel motor home. Pinned in like sardines, we did have overhead rods to hold onto, but who needed them? There was no way one could fall down. After a long ride we unloaded by a very nice-looking jet plane. As I reached the top of the steps, I could see cold air coming from the airducts into hot air. I said to the stewardess, "Are we on fire?" I think she took me seriously. As she tried to explain, I laughed and tried to assure her I understood.

The take-off was very rough due to the rough runway. As I looked out the window, I could see the patchwork on the runway. After lift-off, the flight was perhaps the smoothest I had ever been on.

Two and a half hours to Niigta, Japan, so we were served a complete meal at 2 p.m. Helen and I both agreed that this was the best meal we had ever eaten on an airplane. They even served wine with the meal.

Ninety percent of all the people I have talked to always tell me how they felt after leaving Russia or landing in a free country. They say how wonderful it is to feel the freedom and a great many will tell you that they believed they were being watched all the time. A favorite expression is, "You are looking over your shoulders all the time." I heard this from a couple the morning before we boarded the train in Helsinki, Finland. Well, I know I am an odd-ball, but I did not go to the USSR to look back over my shoulders. If there was someone out there, that was their problem. Personally, once again, I am quite sure this phrase serves only one purpose. . .it makes those people who wake each morning looking under their beds for Communists feel good. I went to see everything I could about the people and how they live. So I spent my entire 14 days trying to see and understand.

As we flew over the Sea of Japan, I felt we had made one great mistake – we should have stayed much longer, and if the opportunity ever comes again, I would love to go back. The USSR is made up of millions of poor, honest, hard-working people whom I had no problem associating with.

With only a brief visit, how can one assess the political climate of such a vast, enormous country? One has to take into account the terrible conflict of World War II as it applied to the USSR. The USSR suffered far in excess of any other Allied nation. A great part of its west from Moscow to Leningrad laid in complete ruins. It is a little hard for me to accept their figures, but they say 20 million Russian people died. during World War II. One also has to take into account the extreme, cold winters. Giving the Communist government credit for extreme hardship, one also has to look at the rest of the world. All of Europe lay in ruins and devastation, beyond one’s imagination. Japan was completely destroyed.

Now these countries had the Marshall Plan of recovery. We visited nine European countries and Japan on this trip. I also took into account that the USSR is the mother country of communism. Now after 70 years of trying to prove the philosophy of Karl Marx and the teachings of Lenin and spreading such philosophy to other parts of the world, there is only one way to say it: Communism has proved to be a complete failure!

The most-used and quoted phrase of communism is, "It is for the masses." Now I assume it means the working class they so often refer to. Everyday I hear this on the television, referring to revolutions and uprisings in all parts of the planet. Now 70 years after its be-ginning, the poor and the masses and the peasants are still there. They are, for the most part, still living in log houses, still traveling over mud roads, still standing in line to buy food, and still kept in the dark as to what goes on beyond their borders. They are mowing hay with the scythe, they are still sweeping the streets with their long brooms.

Seven thousand miles across the USSR, I did not see one single lawn mower, I did not see one single individual home painted, though several had painted shutters. I did not see one pleasure boat, but lots of old men fishing in small boats. I did not see one woman behind any steering wheel.

The villages we walked through all carried their water from a common well. As I see it, after World War II, the rest of the world had their No. 1 goal, to rebuild their economy with the help of good old Uncle Sam. The USSR has spent 43 years building a great army and trying to spread their philosophy throughout the world. As I look at their mighty army today, it reminds me of a joke. A man went to a funeral of a friend who was an atheist. As he passed by the casket, he said, "What a pity — all dressed up and nowhere to go." As I see it, this is exactly the condition of the USSR Army. Ninety-nine percent of all their hardware will end up in a junkyard and die of old age.

There is one more great power on Earth in the same condition. That is the one you and I pay our taxes to. There is one great difference though — we are going into debt for the great part of ours.

One thing concerns me about the Americans who go to the USSR. Let’s first look at what some people in Europe told me. They had been to New York, saw a couple of Broadway shows, the United Nations Building, the Statue of Liberty, and some had even gone to Yankee Stadium to see a ball game. They flew to Orlando, FL, and saw Disney World and Epcot. They think they saw America. More than 90 percent of Americans going to the USSR fly to Moscow, visit Red Square, see a ballet, and see a show of folk dancing. They tour the city, take pictures of the Kremlin, fly to Leningrad, visit the Hermitage, tour the beautiful city, and fly home — and if you are a politician you will be introduced on one of our television networks as an expert on the USSR. I will close this little episode of my life by asking three questions...

1. If you were Gorbachev today, would you open your borders to all religious groups and say, "Come on in, you are welcome?" Think, here come the Moonies, Hare Krishnas, the Backalesh, Jim Bakker, Jim Jones, the Baptists, the Catholics, and the Presbyterians. Do you believe the poor people of Russia deserve this?

2. Do you believe a Russian could travel 7,000-miles in the US as Helen and I did in the USSR and be treated as warm as we were? Of course, this question has very little meaning as there is no way an average Russian can visit the US due to their closed society and their money exchange.

3. And here I am 100 percent serious. I hope, before I die, someone on Earth

(Continued on next page)

(Continued from page 14)

can give me the answer to this question. For years, this has been the most puzzling thing I have encountered on Earth. Perhaps, as I grow older, as I am a young kid of 69, I will grow in wisdom and knowledge and know the answer. Why does every person on this Earth think he or she has the answer to life and spends most of their lives trying to push their beliefs and philosophies onto his fellow man? Think, I don’t care if you are a capitalist, a Communist, a conservative, a liberal, a Democrat, a Republican, an atheist, a Christian, a Moslem, or a Hindu. Why don’t you live your life and believe it and let the rest of the world do the same? How many of you remember the bumper sticker that said "I found it"? Although it did not say so I think it had a religious backing. I have only one thing to say — this could apply to thousands of ideas and beliefs. So you found it, regardless of whom you may be, from Gorbachev to Reagan? If you found it, why don’t you keep it? The rest of us poor suckers on Earth don’t want it. Especially if you insist we take it at the point of a gun.

FOOTNOTE: S.G. SILCOX passed away May 8, 1990.

FNB Chronicle, Vol. 3, No. 2 – Winter 1992

First National Bank

P.O. Box 4699

Oneida, TN 37841

(p8-15)

![]() This page was created

by Timothy

N. West and is copyrighted by

him. All rights reserved.

This page was created

by Timothy

N. West and is copyrighted by

him. All rights reserved.