Henderson Co. TN

Mr. Jonathan Kennon Thompson Smith of Jackson has published seven genealogical miscellanies for Henderson County. He wishes to share this information as widely as possible and has granted permission for these web pages to be created. We thank Mr. Smith for his generosity. Copyright, Jonathan K. T. Smith, 2001

(Page 1)

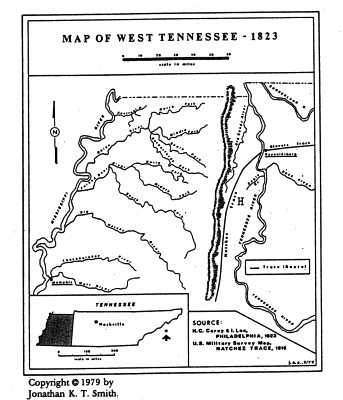

About twenty-five miles of the Natchez Trace of west Tennessee ran a north-south course through Henderson County. (This county was created by the state legislature on November 7, 1821.) The trace ran almost directly south most of the way, turning somewhat to the southwest before it exited the county.

A considerable length of this trace ran directly through what is now the Natchez Trace State Park. This was a well-known fact for many years but as time passed specific details as to its actual route became dim, virtually lost and unfortunately some faulty speculation as to its route has surfaced in recent years.

A particularly regrettable comment was made in THE TENNESSEE ENCYCLOPEDIA, edited by Carroll Van West (Nashville, 1998), page 679, under the name of Natchez Trace Park, "The park's name reflects the assumption that the old 'Natchez Trace' passed through the area; later research identified the original route several miles to the east of the park." The present writer is not privy to what this "later research" involved but it definitely did not include the study of the trace's survey map of 1816 with its attendant commissioners' report and taking note of geologic facts revealed from study of area topographic maps. Otherwise it would have been known to the writer of this entry that the trace did run through a portion of the park.

Western Tennessee had been from time immemorial the hunting domain of the Chickasaw tribe of Indians. The State of North Carolina had allowed speculators to stake out claims in this vast area, principally in the 1780s, as it was considered that the territory would eventually become part of that state and when that became a reality these claims could be legally consummated. Finally, in October 1818 through their representatives the Chickasaws ceded this territory (and southwestern Kentucky) to United States commissioners; the "Tennessee portion" was presented to the State of Tennessee, whereupon in 1819 its legislature accepted the cession and divided it into surveyor districts, ranges and five-mile squares called sections. Then late in 1820 the territory was opened officially for entering legitimate land claims which were confirmed to the claimants by land grant. Generally, residents of Henderson County fell into the Jurisdiction of two older counties, Stewart and Perry. Often in the land grants the name of the county in which land lay was deleted and the land was described by its surveyor district location.

Samuel Wilson, principal surveyor of surveyor district nine early entered 726 acres in what became Henderson County; entered February 6, 1821, surveyed December 28, 1821 and granted April 12, 1822. This acreage was in range five, section nine.[1]

To understand the background of the western-most Natchez Trace, sometimes called a spur of the famous Natchez Trace that ran from Nashville to Natchez, Mississippi, it is essential to have knowledge of the early roads in this section of the state.

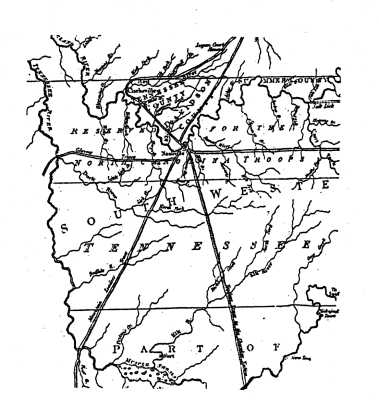

The earliest map of Tennessee reliably showing drawn roads or traces was that one by John Russell entitled MAP OF THE STATE OF KENTUCKY WITH ADJOINING TERRITORIES. It was published in London, England in 1795. That portion of the map relevant to this article is reproduced on the following page.

On examination of this map it may be seen that the three principal traces to the south and southwest of Nashville, Tennessee bore names of prominent persons among the Chickasaws. The forerunner of the famed Natchez Trace is given as "Mountain Leader's Trace." W. E. Meyer, a scholarly student of the early Indians of this area, believed that this alluded to Piomingo, a highly regarded Chickasaw chief known as the "Mountain Leader." [2] It was also called the Chickasaw Trace because it terminated in the territory claimed by that tribe of Indians.

(Page 2)

(The 1795 Russell Map)

Click here for larger image.

The course of the Natchez Trace ran from Nashville to Pontotoc in northern Mississippi "where it connected with trails leading to all sections of the southern United States." In 1801, the federal government secured permission from the Chickasaws to open a wagon road through their lands. In 1806, Congress authorized such a road with the approval of the Chickasaws; one that would run about 500 miles through the wilderness southwesterly from Nashville to Natchez. This road adhered closely to the old "Mountain Leader's Trace." This government road is the famed Natchez Trace over which there was much traffic until about 1827-1830 when the government ceased to use it for postal-travel purposes.[3] It had become evident that sending the public mail by steamboat over the inland waterways would offer faster delivery service.

Clearly shown on the Russell map is the Glover's Trace. This was the ancient Lower Harpeth and West Tennessee Trail. This trace was given the name of Major William Glover, a young man of mixed-blood who witnessed several treaties between his tribe and the United States government from 1801 to l818.[4]

The early map-makers were surprisingly accurate considering the information and technical means made available to them in their labors. Russell's LOCATION for Glover's Trace coincides reasonably well with facts and evidences known about this early trace. The actual point of its crossing the Tennessee River should have been depicted several miles north of the mouth of Duck River. The intention of the mapmaker seems to have been to give the traveller a general idea of where the early roads ran. The southern prong of the trace crossed the river at a point just north of Birdsong Creek in present-day Benton County, Tennessee about six miles north of the mouth of Duck River. Its northern prong crossed at Reynoldsburg, a truly bustling rivertown and until 1837 the county-seat of Humphreys County.

The old Indian trace was used by hunters as well as others traversing the western country. Early in April 1815 four companies of General John Coffee's Tennessee Militia forces made use of the trace, returning to their homes in middle Tennessee (then known as "west" Tennessee), having served under the command of General Andrew Jackson at the battle of New Orleans and in the southern campaign against the British during the War of 1812. The companies of captains Hudson, Joseph Williams,

(Page 3)

Edmondson and Cook turned "off at or near the Chickasaw old towns and crossed the Tennessee River near Reynoldsburg, below [north of] the mouth of Duck River and thence the nearest and best route for their several homes."[5]

The Brevard family of Lincoln County, North Carolina owned the original site of Reynoldsburg (land grant) and retained an interest in the ferry that was operated there from the east bank. As early as October 22, 1813 John F. Brevard had written to General James Robertson (then government agent to the Chickasaws) that "a road from Natchez by way of Reynoldsburg would be more convenient to a great number of people (perhaps a half) who travel down the Mississippi and return by land, than the present road at Colbert's ferry. Such a road, then, would serve as an alternative route to the older Natchez Trace.[7]

On November 15, 1815 Governor Joseph McMinn of Tennessee in a letter to the state legislature of his state, remarked, "I have the honor to enclose for your consideration a copy of an agreement between the United States by their agent Colonel William Cocke and the Chickesaw nation of Indians, for the opening of a road from Reynoldsburg G [T, for Tennessee in original letter] together with a letter of the Secretary of War on that subject in which it will be discovered that the United States are not disposed to bear any part of the expense of opening this road." He encouraged the legislators to consider financing the laying-out of such a road.[8]

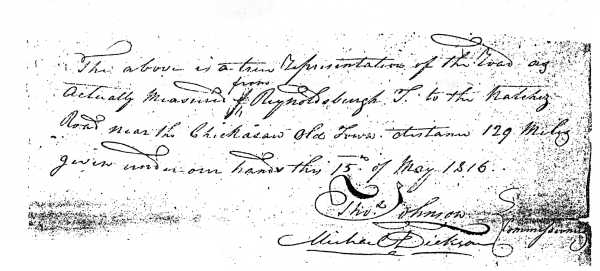

Evidently pressure to establish such a road became such that in December 1815 William H. Crawford, acting U.S. Secretary of War, appointed Thomas Johnson and Michael Dickson of middle Tennessee to serve as commissioners to "mark out" a road, to begin opposite Reynoldsburg and run to Chickasaw Old Town, about seven miles north of present-day Tupelo, Mississippi where it would connect with the older Natchez Trace from Nashville.

These commissioners set immediately to their task, accompanied by representatives of the Chickasaws and laid out this "military road," ostensibly over much of the ancient west Tennessee Indian trail and an extension of Glover's Trace. On May 15, 1816 they made a report to Secretary Crawford:[9]

|

Sir, In obedience to a commission we had the honor to receive from your excellency dated the 28th of December last, appointing us to view and survey a road from Reynoldsburg on Tennessee river to intersect the Natchez road at some point in the Chicksaw nation, in conformity to a treaty made for that purpose with the Chickasaw nation of Indians, dated the 5th day of August, 1815, we, in company with James Brown and Chigcuttach, commissioners appointed on the part of the Chickasaw nation, have performed that duty. The enclosed plat of the road will show the different bearings and watercourses. We have caused the road to be run generally on high dry ground, have opened a bridgeway, caused it to be measured and the miles to be regularly numbered. The road is level and well watered, but little causewaying and bridging will be necessary to make it as good a road as any in the western country. We intersected the Natchez road near the south end of the Chickasaw Old Town, distance from Reynoldsburg one hundred and twenty-nine miles. In surveying this road we passed through a rich and fertile country, particularly the waters of the Mississippi and Mobile. The road at present is uninhabited except twenty-four miles at the south end; the fertility and situation of this country will admit of a number of good settlements on the road to the accommodation of travellers; some of those stands are already marked by the Indians who intend settling immediately. The advantages arising from this road to the citizens of the western part of Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio and the Territories are obvious; it ought to be opened as soon as practicable. |

The commissioners reflected that the federal government would do well to spend the money to establish this road as an internal improvement because if left up to Tennessee and other states it would probably not be funded.

(Page 4)

George Graham, acting Secretary of War submitted the Johnson-Dickson report and plat map to Henry Clay, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, December 5, 1816, in which he explained that the only expense to the government in the survey just finished were for the commissioners who were paid $6 a day when they were actually working.[10]

On March 3, 1817 four thousand dollars were appropriated by Congress for the purpose of "opening a road from Reynoldsburg, on Tennessee River, in the State of Tennessee, through the Chickasawn nation, to intersect the Natchez road near the south end of the Chickasaw Oldtown."[11] In the following October orders were issued by the War office for work to begin on this road and John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of War in a letter to President James Monroe, January 20, 1818, noted that it was considered that this work "is in considerable forwardness."[12]

This "new" road, basically run over much of the very old Indian trail, cut with a wider swath, the rough places smoothed out, miles marked by signs along the way, was finished and opened for traffic in time for the swarm of humanity coming into western Tennessee after it had been purchased from the Chickasaws late in 1818.

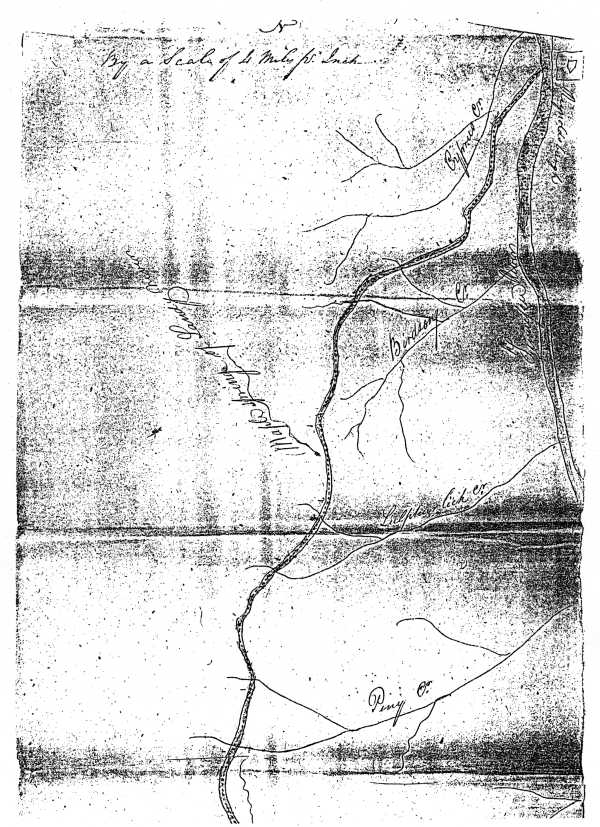

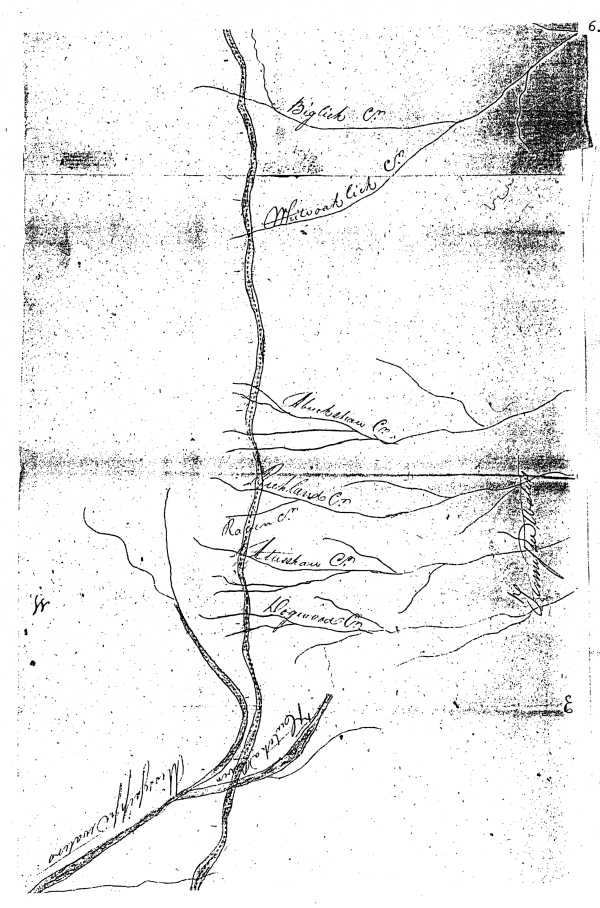

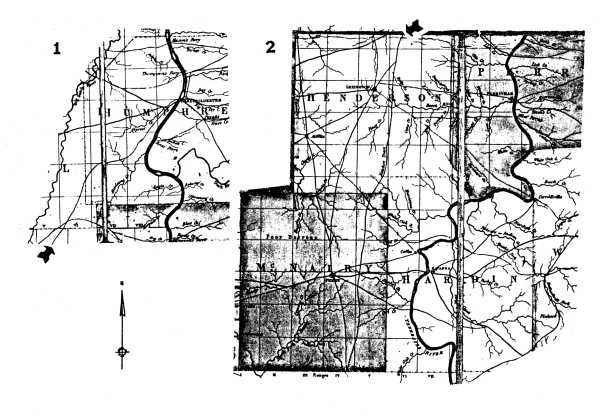

The actual survey map submitted to the War office by Johnson and Dickson makes it possible for researchers to trace the route of this military road generally even if most of its actual roadbed can now only be determined in a few places. The legend on the map provided a basic measurement of four miles to the inch.[13]

This plat map is reproduced on the following several pages.

The old military road long called the Natchez Trace in west Tennessee was also called the Congress Trace, but most settlers knew it simply as "the Notchey," a colloquial rendering of the name. The route began opposite Reynoldsburg which was sited on the east bank of the Tennessee River just northeast of Pilot Knob, a well- known high elevation on the west bank of the river, skirting this high point through the river bottoms, gaining the high hills east of Morris Chapel on old U.S. Highway 70; most of this portion of the old roadbed was inundated by the waters of Kentucky Lake when it was impounded in September 1944 by the TVA; although there is no sign of it now because of altering of the ground surface, the road ran through a portion of the village of Eva on the west bank.

(The southern prong of the Lower Harpeth and West Tennessee Trail — Glover's Trace — crossed the Tennessee River at Ross' ferryboat landing on the west bank of the river several miles south of Reynoldsburg. It too became a major travel route and was known locally as Natchez Trace. An old survey dated August 1822 shows Ross' ferry precisely in its relation to Birdsong Creek (a watercourse noted in the 1816 road survey). Just west of Chalk Level Baptist Church this road merged in a triangular way with the 1816 route.)

From the high hills east of Morris Chapel the road ran southwest, crossing a small stream now called Ford Creek, crossing Birdsong Road just north of the gravelled Flowers Road [rather than the paved road of this name just to the south] and about fifteen miles from the river crossed York Branch (its course suggested on the 1816 map), over Shiloh Church Road about a mile, then diverting somewhat to the west (this stretch now obliterated), crossing Little Birdsong Creek (also suggested on the 1816 map). The roadbed from the river opposite Reynoldsburg to this point has been inundated or otherwise obliterated.

After crossing the Little Birdsong Creek, the road crossed old Highway 69 about six miles south of Camden. The roadbed is still visible here as a wooded ditch on the west side of this highway, running up an incline. New Highway 69 severs the road which continues in a part of it later called the Ben Hatley Road (now abandoned). John Dwight Melton (1902-1985), a scholarly Benton County local historian, showed and walked over a portion of this road, here, with the present writer. He had been told of the road by the Civil War generation who in turn used the old roadbed and heard of its initial opening through their elders.

(Page 5)

(Page 6)

(Page 7)

(Page 8)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Views of' the old trace; one the wooded ditch, former roadbed, about six miles south of Camden and the roadbed as utilized as the Ben Hatley road just to its west |

(Page 9)

The Hatley (old trace) road enters the road now called the Old Natchez Trace Road-Trail, following the ridges for almost five miles, then entering Natchez Trace-Divider Road, running southward and entering the Natchez Trace State Park (in southeast Carroll County); passing the locality of Maple Creek called Maple Springs on the 1816 map, a tributary of Big Sandy River. At eight miles from the Old Natchez Trace Road-Trail intersecting with Natchez Trace-Divider Road the road reaches the location of the Big Pecan Tree.

|

|

Tradition has it that a veteran of the War of 1812, returning home over the trace, then strictly an Indian trail, gave Sukey Morris, member of a squatter family, a pecan which she planted at this location and the remnant of the tree that grew from it is still standing although this venerable tree is on a long decline. The tree surgeons no longer work to keep it alive as it is long-dying and the wind storm of 2000 felled some of its limbs. (In 1973 the tree measured 18'2" in circumference and 106' in height with a limb spread of 126'.)[15] The present writer entertains no particular opinion about the veracity of this old tree's origin but he suspects that there is an element of truth, if only that, in it.

The trace ran due south at this point, along the high ridges at about 600 feet elevation, crossing the Interstate 40 at 4.2 miles south of the Big Pecan Tree and further on at/very near the present-day park headquarters to the northwest of Sulphur Lick Creek now called Sulphur Fork of Cub Creek (although in 1816 most of Cub Creek was evidently called Sulphur Lick). Interstate 40 is located on the Carroll-Henderson counties line at 4.2 mile south of the Big Pecan Tree.

The trace turned slightly to the southwest of the park headquarters, over the travelway called the Natchez Trace (Tennessee Highway 114). (At some point in time, perhaps in the mid-1820s, a local road was laid off from "the Notchey", running towards and into Lexington and it is a major road, well-paved, meandering for miles and is called the Natchez Trace Road.) At about four miles south of the park headquarters the road turned on to higher ridges, now May's Chapel Road, passing on to Alberton Road and running with it until veering southward on Oak Grove Road which intersects with U.S. Highway 412 (Tennessee Highway 20), about fifteen miles south of Interstate 40 and 3.4 miles east of court square in Lexington.

It then crossed to Shady Hill Road, running due south. The 1816 map seems to indicate that at a point about a mile south of the intersection of U.S. Highway 412 and Shady Hill Road the old road crossed a stream later identified as Beech River, keeping ever to a high ridge route, crossing Piney Creek, per se, continuing south along these higher ridges. Piney Creek is actually a moderately-sized tributary of Beech River and feeder of Pine Lake. Evidently the old-time commissioners considered what became permanently known as Beech River as part of Piney Creek. The river was relatively small (now it's a dredged canal), no larger than some creeks. In describing Beech River in his 1834 publication, TENNESSEE GAZETTEER, Eastin Morris wrote that it was a "small navigable stream." (Reprint, edited by R. M. McBridge, Nashville, 1971, page 110)

The road would have run over portions of Big and Little Pine Knobs where tall pine trees grew, fine timber, on both sides of Piney Creek just before it flows into Beech River. The 1816 map shows streams that are suggestive of Haley Creek to the northeast and Lost Creek to the south. About .8 mile southeast of where the road crossed Beech River, was the location of Joseph Reed's log dwelling. He was the first permanent white settler of the county (1818). Some people have thought that the trace of 1816 ran to the front of his house but the course of the trace of 1816

(Page 10)

almost certainly didn't take this lower elevation where just to the south flooded bottom-land would have made travel difficult at some times in the year. It would be more accurate to say that the Reed family settled just off the trace. Figuratively speaking it could be said they lived on the trace so near to the trace was the local road they lived upon. While western hospitality was remarked upon, many times, people didn't always prefer to live directly on such a widely travelled road, what with the constant traffic, riff-raff included, polluters of local streams and travellers' dogs playing havoc with livestock and other animals on the farm.

The road continued southwest from the Beech River area, running several miles west of Reagan into present-day Chester County, crossing Big Lick Creek (probably what is now called Little White Oak Creek), a tributary of White Oak Creek, passing over the latter stream at the Chester-McNairy counties border; thence south fording the numerous streams noted on the 1816 map, bearing different names from those they now bear. The road exited Tennessee at Chambers (near today's Chamber's Creek) close to Acton. From there it crossed Tuscumbia Creek called Hatchie River on the map, shown thereon as entering the actual course of Hatchie River as "Mississippi waters" to the south the road crossed branches of Twenty-Mile Creek (which name this stream still bears), close to U.S. Highway 45, into Lee County and Oldtown Creek to where Chickasaw Old-Town was located about seven miles north of Tupelo.

The Natchez Trace (at that point State Highway 114) enters Henderson County from Carroll County about five miles west of the northeast corner of Henderson County. Matthew Rhea's (1795-1870) "Map of Tennessee," 1832, agrees closely with this computation, allowing for inexact drawing of the old roads. This early map agrees to the route of the western Natchez Trace as delineated in the paragraphs above. In following the old route of the trace through Benton, Carroll and Henderson counties, as the present writer has, one may be favorably impressed with the accomplished effort of the old-time commissioners to run their road "on high dry ground."

That portion of the Rhea map on which the Natchez Trace is depicted:

Click here for larger image.

(Page 13)

From BENTON COUNTY, Tennessee County History Series, Memphis State University, by Jonathan K. T. Smith (Memphis, 1979), page 17:

An H has been inserted on this map to indicate the

general location of HENDERSON COUNTY.

Click here for larger image.

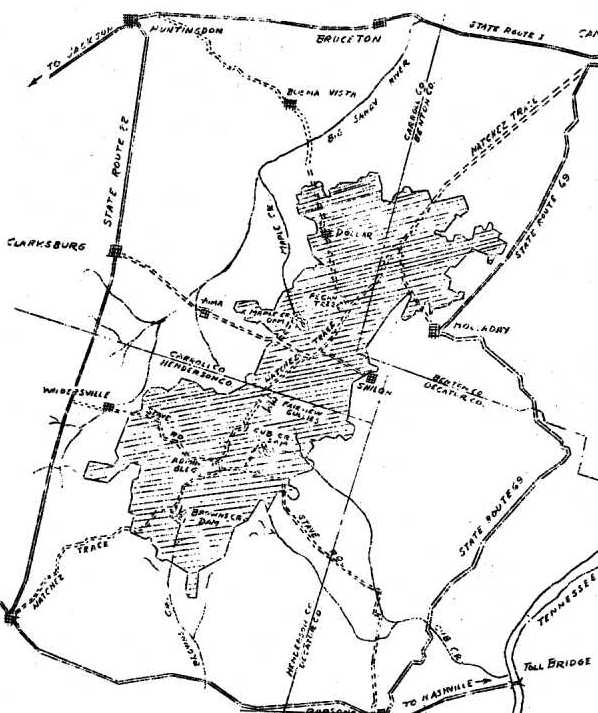

THE NATCHEZ TRACE RESORT PARK AND FOREST

About forty-two thousand acres of land were purchased by the federal government in the mid-1930s in southwest Benton County, southeast Carroll County, north-central and east Henderson County, as part of the "Natchez Trace Project" designed to improve this vast acreage, much of it having been eroded; this was a function of the land utilization procedures of the federal Resettlement Administration. Beginning in November 1935 soil erosion control, road grading, planting of millions of tree seedlings were done in this area, several lakes impounded, improvements made with the assistance of several federal agencies over a period of years.

In March 1939 this area was leased by the State of Tennessee from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and utilized thereafter as a state park known as Natchez Trace, administered for years by the state Division of Forestry. In 1949 the Division of State Parks (Tennessee) assumed administration of the park. It is one of west Tennessee's most popular state parks.

(Page 12)

The Natchez Trace area as depicted in a federal Resettlement Administration booklet about 1940:[13]

(Page 13)

REFERENCES

1. General Land Grant Book T, page 37. Land Grant #16918.

2. INDIAN TRAILS OF THE SOUTHFAST by William E. Myer. Reprint, 1971, page 78.

3. IBID., pages 77-78, wherein more detail is found about the Natchez Trace (1801).

4. BIOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL INDEX OF AMERICAN INDIANS, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1966, volume 3, page 555: treaties bearing dates of October 24, 1801, September 20, 1816 and October 19, 1818. The fact of the major's having been a mixed-blood was alluded to in a letter written by Colonel John Sevier to Major Glover of the Chickasaw "nation," dated December 15, 1788, "I am glad to hear that you are a great warrior and part of our blood." THE STATE PAPERS OF NORTH CAROLINA, edited by Walter Clark, 1907, volume 22, page 720.

5. NATCHEZ TRACE PARKWAY SURVEY, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1941, page 86. Hereafter cited as Natchez Trace Survey.

6. AMERICAN HISTORY MAGAZINE, Nashville, 1900, volume 5, page 292.

7. Natchez Trace Survey, page 103; of the Reynoldsburg branch of the Natchez Trace, "but it cannot be doubted that it was intended to serve as a substitute for the old trace."

8. AMERICAN HISTORY MAGAZINE, Nashville, 1899, volume 4, page 319.

9. AMERICAN STATE PAPERS, Class X, Miscellaneous volume 2, Washington, D.C., 1834, page 402.

10. IBID., page 401.

11. IBID., page 468.

12. IBID., page 470.

13. The original map consists of three legal size papers glued together. Scale of miles, four miles to the inch. File J-96 (1816), letters received by the Office of the Secretary of War, Record Group 107, National Archives and Records Administration, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C. 20408. The present writer obtained photocopies of the map at the actual size of these map sections.

14. Benton County Survey Book A, page 24. In the same book, page 20, an 1821 entry refers to the 1816 road as the "road from Reynoldsburg to Natchez."

15. Interview, Jonathan Smith with Alisha Weber, interpretive specialist, Natchez Trace State Park, at Park Headquarters, November 14, 2001. The precise age of the Big Pecan free cannot now be determined because its rotted interior has long been filled with concrete to reinforce it.

volume I · volume II · volume III · volume IV · volume V · volume VI · volume VII