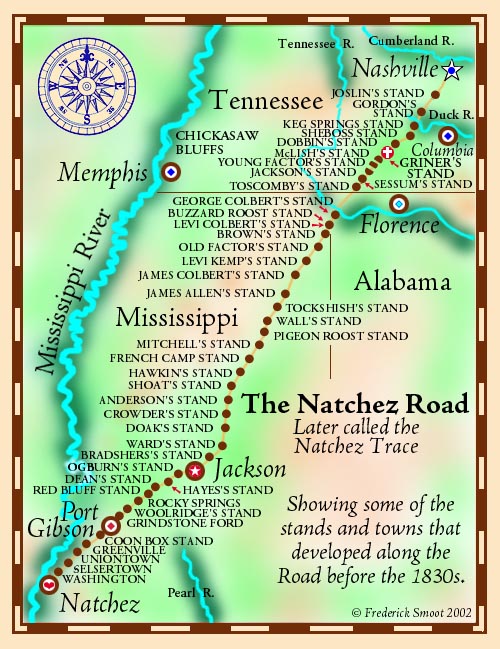

Originally, the Natchez Road was a series of linked game trails, latter used by America’s ancient First People.

In historic times, the two major First Nations that controlled the area through which the trail ran were the Choctaw and the

Chickasaw. When the old trail started to receive names, it was given three, one for each part.

From Natchez northeastward,

it was called the “Path to Choctaw Nation,” the middle section through the Choctaw Nation

was known as the “Choctaw-Chickasaw Trail, ” the northern most leg of this rude path ran

through Chickasaw Nation and to Nashville Tennessee. This part was known as the “Chickasaw

Trace.” The name “Mountain Leader’s Trace” was applied to at least the nothern part during the early days.

As a whole, the trail became know as the Natchez Road, the Federal Road, the Boatman’s Trail, and

finally, the Natchez Trace.

Part of today’s Mississippi and Alabama became the Territory of Mississippi on 7 May 1798.

The narrow strip of land contained “Path to Choctaw Nation, ” that is, Natchez through

Port Gibson into Choctaw country. The eyes of the United States were starting to look south.

In 1800, the U.S. Congress established a postal route between Nashville and the capitol of the Territory of Mississippi in

Natchez. The mail route was known officially as “Road from Nashville in the State of Tennessee to the Grindstone

Ford of the Bayou Pierre in the Mississippi Territory.”

In 1801, the United States treated with the Chickasaw, and obtained the right to build a road through

the Chickasaw Nation.

From the 1801 treaty:

“The Mingco, principal men and warriors of the Chickasaw nation of Indians, give leave and

permission to the President of the United States of America, to lay out, open and make a convenient

wagon road through their land between the settlements of Mero District in the state of Tennessee, and

those of Natchez in the Mississippi Territory, in such way and manner as he may deem proper; and the

same shall be a high way for the citizens of the United States, and the

Chickasaws.” (See full treaty text)

On 30 April 1803 the United States signed an agreement with France to purchase Louisiana country.

Soon after, this vast tract of land became the Territory of Louisiana. Early use of the Road was for commercial and

private inland travel, it soon became an important military road. In 1803 and 1804, Tennessee Volunteers marched over it

to insure that the Louisiana Purchase agreement would not be disputed by Spain.

On 27 March 1804 a large

tract of land was added to the Mississippi Territory. While the Natchez Road never reached into the Territory

of Louisiana, it is important to recognize that the United States was moving southwest, and for about thirty years,

the Natchez Road played a important part in the development of that southwestern country.

(See

the Territory of Mississippi map)

In the early 1800s, many Tennessee and

Kentucky farmers would take their farm goods to the lucrative New

Orleans market. They built flatboats for their goods. They floated down

the Cumberland, Duck and Tennessee Rivers to the Ohio River, then to the

Mississippi River and southward to Natchez and New Orleans.

When is was time to return, the flatboats would be sold,

or if necessary, abandoned. If they had made a good sale, they might buy a

horse for their return trip. If the sale was bad, they might return on

foot. In any case, in those early years, the route of choice was the

Natchez Road. When the Kentuckians arrived at Nashville, they would

continue to central Kentucky via the “Wilderness Road.”

It is these return trips that have made the Natchez

Road famous (or perhaps infamous would be a better choice of words here).

There are stories of murders along the Natchez Road. The farmers

would be killed, then disemboweled, their body cavities filled with

stones, and then the bodies would be submerged in some nameless creek.

To the farmer, the stands would

be a welcome sight. Even the most rude stand could offer some protection

and a meager meal. Generally, the stands were located five to six miles apart,

but not so in the early times of the road.

The most well known death along the “Trace” is

the 11 October 1809 death of Meriwether Lewis, Governor of the United States Territory of Louisiana.

This man, famous as co-leader of the

Lewis and Clark expedition,

allegedly committed suicide at Griner’s Stand. Lewis’s traveling companion,

Major James Neely, arrived at the death scene a few hours after the event.

Major Neely wrote this to Thomas Jefferson: “It is with extreme

pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis,

Governor of Upper Louisiana who died on the morning of the 11th Instant and I

am sorry to say by Suicide.” Still, there are many today who question the suicide,

believing instead that Lewis was probably murdered.

Until the time of removal during the late 1830s, many Indian

families could operate stands (wayside inns) and ferries needed by travelers along the

road. Those stands and ferries proved to be lucrative for some of the lucky few who owned

the concessions. Still, by 1825, many stands had gone out of business.

During the heyday of the trace, thousands of travelers used the road. Unfortunately,

many of those same travelers illegally settled on Chickasaw and Choctaw land, especially during the 1830s.

Since the Trace favored higher ground, i.e., ridge lines in order to avoid swamps, the early settlers

would actually look for bottom land with richer soil than the ridges. The white settlers

had a insatiable appetite for land so they squatted on Indian land and waited

for the U.S. government to obtain “legal” title. When

that happened, the Chickasaw and Choctaw were evicted to west of the Mississippi

River.

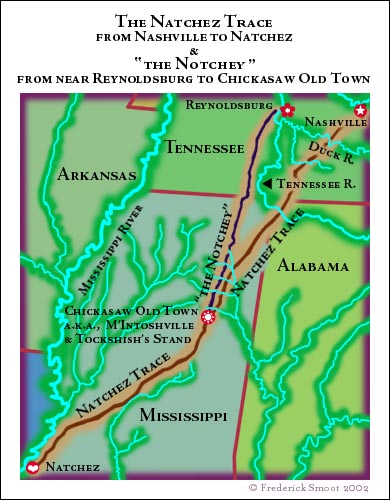

The West Tennessee Natchez Trace †

West Tennessee, that is, that part of the state which is situated west of the north

flowing part of the Tennessee River was Chickasaw country until they ceded all their land there (and in Kentucky too)

to the United States on 19 October 1818. The treaty, known as the

Great Chickasaw Cession opened west

Tennessee for legal settlement.

Prior to the cession, the idea of a military road was conceived to run from

the west side of the Tennessee River opposite of Reynoldsburg in Humphrys County south to Chickasaw

Old Town in the Territory of Mississippi. At Chickasaw Old Town, this new road would connect to the original Natchez Trace.

In 1817, the United States Congress appropriated four thousand dollars for the purpose

of opening the road. This road became known under a number of names, including Natchez Trace, Congress Trace, and Notchey.

Matthew Rhea’s 1832 Map of Tennessee shows the Notchey as the “Natchez Trace.”

See enhanced detail section of West Tennessee from

Rhea’ map. (83k)

The advent of steamboats in the 1820s reduced the importance of the both

the original Natchez Trace and “the Notchey.” Much of those old roads became part of rural

road systems. Today, the original Natchez Trace is a beautiful scenic parkway while the Notchey is in part, country roads,

and in part, abandoned.

Notes

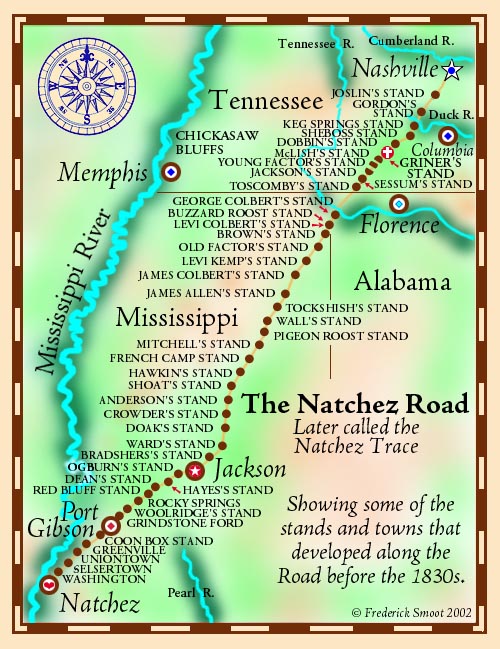

The stands shown on our map represent the most well

know stands, but be aware that the stands came and went, and some

changed names. Not all of these stands existed with these names at the

same time. Additionally, in places along the route there were

parallel roads. A lower road might be easier in the summer, but less

favorable in the early spring.

Chickasaw Old Town; a.k.a., Chickasaw Oldtown, M‘Intoshville, McIntoshville,

McIntosh’s, Tockshish, and

Tockshish’s Stand. A postoffice

was established there before 1803.

Bibliography

Coates, Robert M.,

The Outlaw Years: The History of the Land Pirates

of the Natchez Trace Macaulay Co. 1930. Stories of murder and more

along the Natchez Trace. Often found in used

books stores. It has been reprinted by University of Nebraska

1986, ISBN: 080326318X and perhaps others.

Daniels, Jonathan,

The Devil’s Backbone: The Story of the Natchez

Trace.

McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1962. More stories of murder along the Natchez

Trace.

Davis, William C.,

A Way Through the Wilderness: The Natchez Trace and

the Civilization of the Southern Frontier. HarperCollins Publishers,

NY, 1995. ISBN 0-06-016921-4

This is a excellent and worthy work. Much of

our map information came from this book.

Smith, Jonathan Kennon

Thompson, The West

Tennessee Natchez Trace, an online publication of David Donahue.